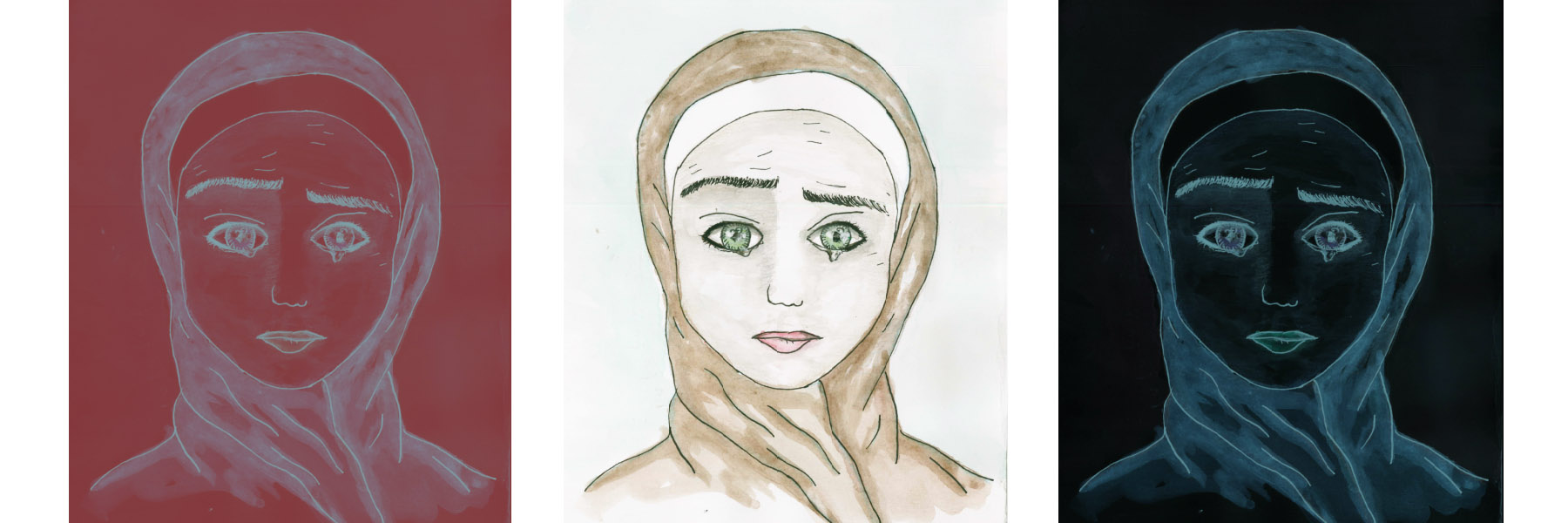

STORY BY HEATHER M. SURLS

ILLUSTRATIONS BY RAHAF ADNAN OUDAH

From afar, the plight of refugees can be hard to understand. Why did they leave their homeland in the first place? What is daily life like in the place in which they’ve tried to find safety? Will they return home one day? Our correspondent in Jordan takes us deep into the lives of two Syrian families who fled to neighboring Jordan and now long to return home as most of Syria regains a level of calm. Learn why the question of whether to return to Syria has no straightforward answer.

Editor’s note: The reporting and interviews for this story were completed earlier this year, but we weren’t able to publish the article before our months-long publishing hiatus for building the new Anthrow Circus website. However, all that’s recounted here remains eminently relevant in light of ongoing world events. All details were current as of late August.

*All names of families interviewed for this article have been changed to protect them.

Imani, Hassan, and their four children live at the end of an alley in Marka, an eastern district of Amman, Jordan’s capital city. This is the best apartment they’ve lived in since fleeing Syria in 2014. Their previous home festered with mold, and the paint flaked from humidity. The interior walls were so thin that sometimes, if they touched the walls, they’d get shocked from the electric wiring. One night, the building’s roof actually collapsed on their upstairs neighbor.

This current first-floor apartment is a huge improvement. A network of relatives from Raqqa Province in northern Syria lives in the apartments above them. Three big trees—olive, mulberry, and fig—shade the walled garden around the building and the empty dirt space where the kids can play. School is within walking distance.

Though their living conditions have improved, Imani has started to dream of something more.

“I hope I will return [to Syria],” she says, “and I’m afraid I’ll return, at the same time.”

As the Syrian civil war quiets down—with the Islamic State group mostly squelched and President Bashar Assad’s regime in control of most of the country, minus the northwestern province of Idlib—many of the 660,000 Syrian refugees registered by the United Nations in Jordan are weighing their options: persevere in Jordan, where rent soars and hope of resettlement in Western countries dwindles, or return to their homeland, where a shattered economy and an uncertain future await. As I hear through weekly volunteer work with Syrians, the decision is complex and heartrending.

Jordanian public opinion expresses this same ambivalence. In February Jordan’s Roya News headlined Prime Minister Omar Razzaz’s opinion that “Syrian refugees have no desire to return to their homeland.”

One month later, the Jordan Times reported the opposite. “The overwhelming majority of refugees, at least the ones that are in Jordan, want to go back home,” King Abdullah II is quoted as saying. “And unless we empower them, unless we give them education, unless we look after them, give them opportunities, how are they going to be able to go back as positive building blocks of society?”

FROM A BESIEGED TOWN TO JORDAN’S CAPITAL

The pressure to leave Syria built slowly, Imani says. When the revolution began in 2011, she and her children lived in a town in Raqqa Province, far from the southwestern district of Deraa where the uprising started. But even in Raqqa Province, where they had lived comfortable and quiet lives, prices started to rise. Power shortages limited electricity to one hour a day. Occasionally, they’d hear people screaming, being taken from their homes by the Syrian government regime. Fear crept in.

Then bombs started dropping. The planes tended to come in the evening around sunset, the time for evening prayers. Four times, Imani took her kids and hid in a building near their home with a stronger foundation and basement. Once they took shelter there with neighbors all night.

By June 2014, Imani’s town was fully under siege by the regime. She and her then-three kids escaped in a truck, taking just their clothes with them. They didn’t have passports; they’d never had the need for them, and they left suddenly, with no time to prepare documents. The truck delivered them to Syria’s southern border, where they spent seven days sleeping on the ground, waiting for permission to enter Jordan.

“More than once I went to the officers who were on the Jordanian border,” Imani says. “I started crying and I told one of them, ‘My children are hungry, what can I feed them?’ He started to cry for me too.”

After they were transported to the Azraq refugee camp, 90 kilometers into the Jordanian desert, Imani’s oldest child contracted a kidney infection, probably from drinking the yellow, dirty water they were offered. After some testing at the camp’s health center, the staff recommended that her daughter be sent to a hospital in southern Amman for treatment. The daughter would have to go alone, without her mother.

Imani contacted her husband, Hassan, who was at that time in Amman. Like many men in their village in Syria, Hassan had been a barley and wheat farmer and shepherd. But it was impossible to make a living like this, he says, so since 2000 he had been traveling to Jordan for work. Though Hassan had made multiple attempts to return to Syria since the war began, he’d been denied entrance both from Jordan and Lebanon and hadn’t seen his family in two years. Now Imani asked him to meet their daughter at the hospital.

At the hospital, doctors requested a biopsy for their daughter, and Imani, still in the camp, broke. She had to find a way to get to her child. At her husband’s advice, she paid a smuggler to sneak them out of Azraq and deliver them to Amman. (Once registered as camp residents, refugees are only permitted to leave under certain conditions.) At 1 a.m., she picked up her two sleeping children and joined four or five other families on the edge of the camp, where soldiers patrolled.

Though they had paid him all they had, the smuggler never showed up. As Imani and the other families waited in a dry riverbed, trying to avoid detection by the guards, a woman told her that her nephew had recently died from same illness Imani’s daughter had.

“When she told me that, I just wanted to walk,” Imani says. “I wanted to go. I threw down all the things I was carrying—I’d taken a few clothes for the kids—I threw them down, threw everything, picked up my kids, and ran.”

Somewhere on a nearby road, Imani found a car that took her to Amman. Just 10 days after entering Azraq, she left the camp and began her life as a refugee in the capital city. According to the U.N. Refugee Agency’s year-end figures, 84% of Syrian refugees registered in Jordan in 2014 had, like Imani and her family, taken up residence in urban areas.

DANGER ON ALL SIDES

Aisha pulls the electric heater closer as we settle on the cushions in her living room. She brought these from the Zaatari refugee camp where she, her husband, Khalid, and their then-seven children lived for nine months after fleeing kidnapping and death threats in their home city of Deraa. Khalid sits cross-legged across from us as kids run in and out of the room, his big hands folded in front of him. He matches the lone framed photograph on the wall—one of him working in Damascus’s central intelligence department, the Syrian flag beside him.

Aisha sets a tray of sweetened instant coffee beside us as Khalid explains his dilemma. As a former employee of Assad’s government, Khalid had the opportunity, at the time of our spring 2019 interview, to return to his old job, reportedly without fear of punishment, before April 9, 2019. In October 2018, Assad granted amnesty to any military employees who fled during the civil war.

Although the promise of steady work is alluring, this is no clear-cut decision.

“I want to go back to Syria,” Khalid says, “because—khalas—all other ways have been closed for me.”

Since arriving in Jordan in 2012, Aisha and Khalid’s family has faced similar struggles to all Syrian refugee families. But last fall, their strained situation became more desperate when their son became the victim of a traumatizing criminal act. Though he has personally gone to the U.N. multiple times to explain his circumstances and plead his case for resettlement in the West, Khalid has made no progress.

“My mental condition has gotten to 90% bad,” Khalid says. “Sometimes when I’m walking in the street, I am preoccupied. People sometimes greet me and I don’t pay attention. Why? Because I’m thinking. My mind is always working on this story, what happened to us in Syria and here.”

When the revolution began in 2011 in Deraa, a large portrait of President Assad hung outside Khalid and Aisha’s home there. The portrait had been there for 10 or 15 years, Khalid says, and though it made their house a target for the Free Syrian Army (FSA), he didn’t remove it because he didn’t want to be accused of defaming the president. Khalid had been working for Assad’s intelligence department for more than 20 years, monitoring Syrian civilians and doing background checks on military personnel.

“My husband was holding onto the regime, not because of his love for the regime or something, but because of his love for his life,” Aisha explains. “He wanted to provide for his children.”

Aisha and Khalid didn’t realize it, but once the revolution began, their house was being monitored by the FSA. Often Aisha was there alone with the children, since Khalid worked a few days at a time a couple of hours north in Damascus. One night, at three in the morning, the FSA sprayed their home with live fire. After this attack, the family moved into Aisha’s sister’s building and stayed there a month and a half.

A couple of months later, after delivering their seventh child, Aisha and Khalid were attacked while driving home from a funeral. Masked men surrounded their car and threw large rocks through the windows. One hit Khalid in the head, sending him to the hospital. After this attack, they moved to Damascus for four months. Even there in Syria’s capital, the rebels continued to send threats. “If you don’t leave the regime, we’ll kidnap your son.”

So in October 2012, Khalid and Aisha decided to leave Syria. They traveled south to a village near the border and stayed there a couple of nights before entering Jordan at the Zaatari refugee camp, which is currently home to around 80,000 refugees.

But even in the camp, Khalid was being watched.

“After the FSA heard that we had left, they were not pleased,” Aisha says. “They wanted to be done with him—they wanted to kill him.”

The FSA in Syria contacted rebel spies in the camp, and less than a week after the family’s arrival, men kidnapped Khalid, took him to an empty tent, and began to beat him and accuse him of being a spy for the regime, of poisoning the camp’s water supply. The Jordanian army intervened, probably saving Khalid’s life.

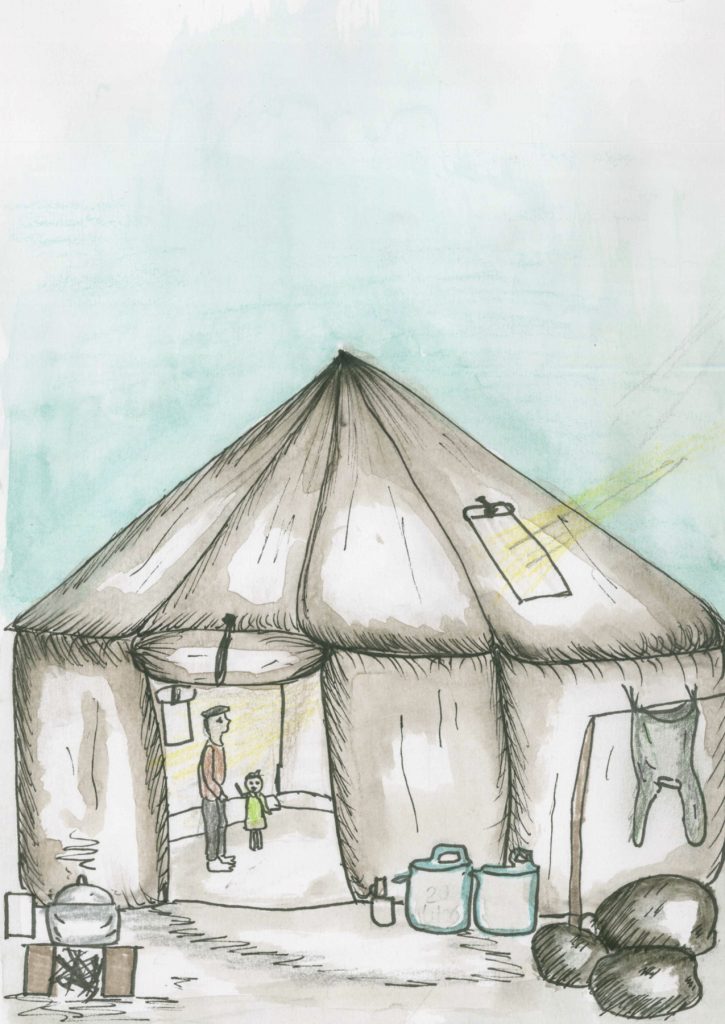

Yet the family stayed eight months in Zaatari, enduring extreme heat and cold. At that time, early in the camp’s construction, refugees still lived in tents, used communal toilets, and shared kitchen spaces. Once the family’s tent collapsed on them under snowfall. Because of the dust and storms, Aisha began to suffer from asthma.

So when a relative in Amman suggested they come to the city, they took the chance.

CHALLENGES IN THE CITY

When Aisha and Khalid left Zaatari for the suburbs between Amman and Zarqa, they didn’t have official permission to leave the camp. Because of this, it took two years to get their IDs reissued. At one point, they didn’t receive food coupons from the U.N. for three months. In those early months, they sold everything—even their gas canister and kitchen staples—and took out a loan in order to pay for an apartment.

Though the Jordanian government did not begin issuing work permits to Syrians until 2016, one of their sons, then 13, found a job, and even their older daughters worked labelling perfume bottles. Aisha started to do basic sewing projects in her home, earning just one Jordanian dinar per day ($1.41). Then she worked in a factory for a month, before an unexpected pregnancy.

In the street, Aisha and Khalid’s boys began to face discrimination. Other boys hit and taunted them when they walked to and from school or ran errands. Things culminated in late 2018, when Rami, then nine, became a victim of crime. From that time until the present, the family has been tied down by the Jordanian judicial system, unable to leave the country until their case is finalized. They’ve also sought counseling—not only for Rami, but also for Aisha, who has suffered psychologically as much as her son.

For Imani and Hassan’s family, in the years they’ve spent in Marka, their children have faced similar prejudice in school and their neighborhood. Imani says that if she had known what life was hiding for them, she wouldn’t have had children.

“The Syrian, he’s gotten a black spot—that he’s Syrian, immigrant, displaced,” she says. Jordanians say, “‘You came to us, ruined us. First you ruined your country, and then you’re coming to ruin our country.’ Okay, but me, what did I do? Yes, some people destroyed the country, but what did I do? What did my kids do?”

Like Khalid and Aisha, Hassan and Imani have faced continual financial pressures in Jordan. Though Hassan has been able to work as a tiler and painter, work is not always consistent. Last winter, for example, he spent a few months without employment, which brought their landlord to their door every few days, demanding rent and threatening to evict them. In addition, their daughter’s health problems have lingered, and treatment has only recently begun to be successful.

“I don’t feel like anything has changed,” Imani says. “For a while I’ve started saying to Hassan, ‘I want to return, I’m finished. I want to go back.’”

THE DILEMMA OF WHETHER TO RETURN

Late last year, the UNHCR projected that up to 250,000 Syrian refugees could return to Syria in 2019 from countries like Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. UNHCR spokesperson Lilly Carlisle told Anthrow Circus that as of the end of July, 26,000 Syrians residing in Jordan have voluntarily returned home since the October 2018 reopening of Jordan’s northern border with Syria. This border had been closed for more than three years. Of these, 20,000 returned home in 2019.

Khalid’s younger sister and brother-in-law, who spent several years in Jordan and listened while I interviewed Khalid, returned to Syria before April 9, taking advantage of the amnesty offered by Assad’s regime. Aisha says her brother-in-law has returned to his job in Damascus, that his wife is living back in Deraa with their children. Their biggest complaints are severe inflation, which has caused prices to quadruple, and lack of consistent electricity.

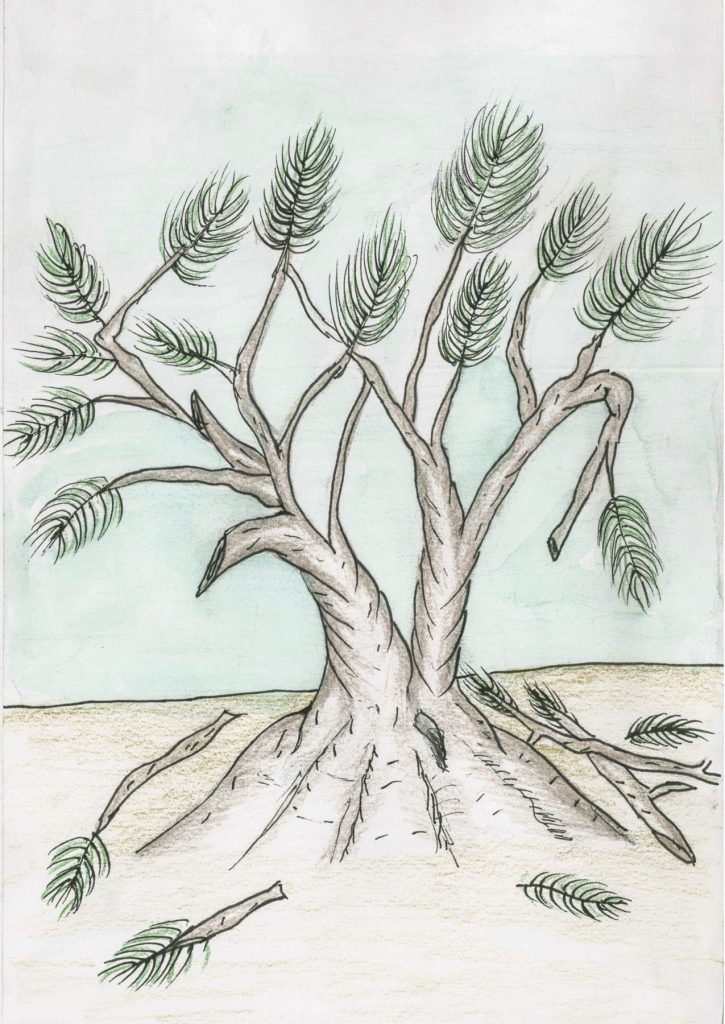

Imani’s cousin Dima, who used to live in the apartment upstairs, also returned to Syria this spring with her husband and six-year-old son. Before they left, Dima told me how she looked forward to returning to their still-standing home in Raqqa, to the joy of being close to her parents, who had managed to stay in Raqqa. She mentioned her family’s orchard, filled with pomegranate and apricot trees, how she longed to care for them again.

Imani tells me Dima’s news when I see her—how she’s working for another orchard, tending to olive trees, and how her husband has started working in a small restaurant. Their son is going to school, though the education system is currently weak, with schools often putting upper grade students without experience in charge of younger students. We watch a video from Dima—she pans the empty countryside at sunset—and look at a picture of her and her husband standing side by side on their tilled land, smiles on their faces.

Losing the proximity of her cousin has been difficult for Imani. She longs to be reunited with her parents, to see her two brothers, who recently returned from Saudi Arabia to Raqqa to find brides. She wants to be at their weddings, to live in her old home without the pressure of rent payments, to be where her children will know the love of their grandparents.

But Hassan says that if Imani goes back, she’ll have to go alone. If he returns, he could be conscripted or arrested by the regime—a fear I’ve heard expressed by all families with men of military age. Though all Syrian men are legally required to serve two and a half years in the army, service often extended to five or more years under Assad’s rule. And with Syria’s history of human rights abuse, most families fear how the regime could treat their husbands and sons. Men have disappeared into the prison system for years, facing torture and sometimes death.

And even Aisha and Khalid, who have been promised safety by the regime, aren’t sure what would really happen if Khalid were to return. Reports of interrogation, arrest, and torture regularly filter back to Syrians abroad. As of this article’s final edit, Khalid has not returned to Syria, opting to stay with Aisha and his kids until Rami’s court case is finalized. If they had some assurance from the U.N. that they could immigrate to the West, they tell me, waiting in Jordan would be much easier.

“We don’t know what will happen to us in Syria,” Aisha said when Khalid was still considering returning by the April deadline. “What will they give us? Will they punish us? What will they do to us—will they honor us or mislead us? We don’t know.”

Heather is grateful to Waleed and Sujud for their linguistic, cultural, and political insights that aided her work on this article.