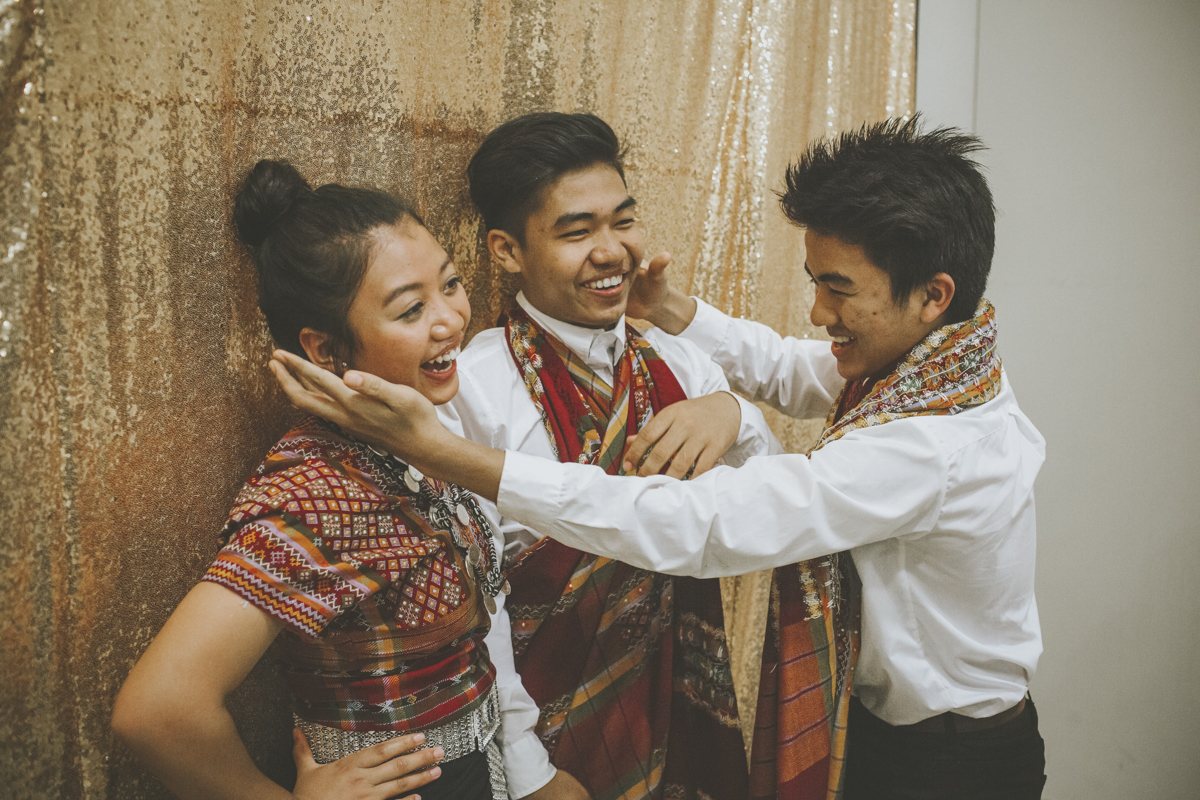

This dance troupe composed of Chin young people performed at a World Relief event in 2017. They are dressed in the costumes traditional for their ethnic group.

STORY BY HEATHER M. SURLS

PHOTOS BY HAWA IMAGES, USED BY PERMISSION OF WORLD RELIEF CHICAGOLAND

Years ago, a neighbor gave me a glossy 4×6-inch picture of Myanmar politician Aung San Suu Kyi backed by the red and yellow of the National League for Democracy’s flag. I no longer remember the giver’s identity—at that time my Burmese neighbors numbered in the hundreds—but since the country’s late-January military coup that imprisoned Suu Kyi and others, Myanmar (formerly Burma) has been on my mind.

I’ve not visited the land that travel guides claim is packed with gold-crusted pagodas, but from 2011 to 2014, I lived in an apartment complex housing Burmese refugees in the Chicago suburbs. My kaleidoscope of neighbors, representing several of Myanmar’s 135 ethnic groups, had been resettled primarily from refugee camps and cities they’d fled to in Thailand and Malaysia. This staggeringly diverse sliver of men, women, and children were among more than 73,000 Burmese refugees resettled in the U.S. between 2005 and 2014.

When I reflect now, those three years among the Burmese were like bootcamp for me, a foundational, immersive course in relating to people different from me. At that time, I didn’t realize this would be a preparatory phase for longer-term work among refugees. I moved in with the idea that I would help them—I did not know how much my neighbors would shape me.

While living with the Chin, Karen, Karreni, Zomi, and Rohingya, I didn’t have a full-time job, just occasional freelance projects that I worked on at my kitchen table. In the summer I kept the window open to let in the humid Midwest breeze, the ping of tonal languages, and the screeching of kids playing in the parking lot. I had an open-door policy, and so my neighbors came: adults with mail to be read, phone calls to be made, and assistance to be applied for, kids with homework to be solved.

I often felt exhilarated when helping my neighbors, when I got to step in as savior and be thanked profusely in broken English for fixing an insurance snafu or suggesting new batteries for a smoke detector that’d been beeping for hours. I felt good about myself when, on my first day in the apartments, I gave a Karen neighbor a couple bags of chamomile tea for her sore throat. I thought, I’m helping a poor refugee who might not have tea.

I was wrong—in that case and in so many others. My neighbor with the sore throat had needs, yes, but she also had much to offer me.

Though being the dispenser of services and advice made me feel good, I needed to learn how to receive from my Burmese neighbors, to erase the impulse to always be the one giving. Receiving from them guided me to stop seeing them as victims of the persecution that had forced them from their homeland and start seeing them as new contributors to the religious, social, and economic fabric of my country. Had I perpetually stood in the giving position, they could have turned into mere projects, eliminating the possibility of mutual respect and friendship. So when their paperwork was done, I set aside the inherently powerful role of cultural broker and saw them transformed: No longer defined by their needs, they sprang into three-dimensional human beings with gifts and dreams, personalities and passions, foibles and failings.

Gratefully, since I was surrounded by them 24/7, I frequently experienced my neighbors as more than beneficiaries. When the Karen and Chin and Zomi invited me to their prayer meetings—sometimes with 60 people packed into a living room to sing hymns—I witnessed their giftedness as ministers, as strong and capable leaders in their communities. I watched the entrepreneurial Rohingya family downstairs load and unload their little storage truck at all hours of day and night, part of operating their Asian products business.

Once I sat with a group of Chin women, gathered for a reason I no longer remember. When the formal part of our meeting ended, they set a plate of homemade doughnuts in front of me—warm rounds of slightly sweetened fried bread—and a mug of tea with condensed milk. Then they ignored me, chattering and joking confidently in their language, doing what they could not do in English. I faded into the background, and as someone accustomed to being the center of attention when I was with them, the background was a very good place for me to be.

For citizens of a resettlement country like the United States, it can be tempting to reduce refugees to cardboard cutouts: people who are materially poor and therefore mentally, spiritually, and socially poor as well. We may tend to think of our responsibility toward them in this way: Get them in schools, teach them English, and make them good Americans (and the sooner the better, so we can understand them and they won’t be so awkward and inconvenient).

Could it be that this attitude springs from “a shriveled, failed imagination”? James K. A. Smith, a philosophy professor and intellectual, uses this phrase when discussing possible causes of contemporary religious, political, and cultural chaos.

“I’ve abandoned all hope that we can think our way out of the mess we’ve made of the world,” writes Smith. “The pathology that besets us in this cultural moment is a failure of imagination, specifically the failure to imagine the other as neighbor. Empathy is ultimately a feat of the imagination.”

Though Smith goes on to argue that the arts will ultimately revive that imagination, his words seem apt in this context as well: Imagination is what we need when encountering people unlike us—whether refugee or immigrant, whether someone from a different religion, race, socio-economic bracket, or sexual orientation. Imagination does not require that we agree with the person in front of us, but it does demand that we see others as human, not alien. Imagination should spawn healthy forms of tolerance that allow people with different worldviews to interact in a spirit of respectful dialogue. Imagination does not permit us to demonize or stereotype but to see others as complex, multi-faceted individuals.

As I stand in my kitchen in Amman, Jordan, I remember some of these individuals—my Burmese neighbors in Chicagoland, most of whom are now U.S. citizens. While anti-coup demonstrators continue their resistance in Myanmar’s streets, I fry turmeric- and garlic-infused rice, recalling the day in 2011 when I first tasted my neighbors’ fried rice—a meal packed neatly in a three-story tin with tender, diced carrots. I ate it in a park with a Karen family whose five-foot father worked at a meat-packing plant and drove a 15-passenger van.

I remember my neighbor with the sore throat and the countless meals she fed me, how tight our friendship became as she endured domestic abuse and I had my first child. Once, during a birthday party, I worked with her and her oldest daughter in their kitchen, preparing starchy tangles of rice noodles by cutting them with shears and loading them into plastic strainers. Her daughter mentioned how the Karen don’t let a visitor help in the kitchen unless they are close.

“So this means you are family,” she told me. Me, the white girl from two doors down who couldn’t even say “hello” in their language, much less cook a decent pot of rice. The task-driven, time-oriented American these women had chosen to accept.

You and I cannot determine how things will turn out in Myanmar, but by looking and listening, by being curious and humble, by opening our hearts to people in our lives who are unlike us but not fundamentally different, we can honor the people of Myanmar who have become our neighbors and its people who are back home calling for basic human rights at great risk to themselves. Inner work like this can change our thoughts and attitudes, which will lead us to recognize the humanity of the other and affect our responses and actions toward them. Personal choices like these will eventually filter upwards, bringing change to government policies and cultural outlooks.

As we expand our imaginations and learn to practice empathy, we will have the capacity to begin seeing the stranger as neighbor.

To learn more, check out Anthrow Circus’s recent article featuring a woman from Myanmar offering context for the suffering her country is experiencing. You may also find our other stories about Myanmar’s minority Rohingyas informative, as well as our stories featuring people who are refugees.

In addition to serving as Anthrow Circus's assistant editor and proofreader, Heather Surls regularly contributes stories to the site, drawing inspiration from her relationships and experiences in Amman, Jordan. Her reporting and creative work have also appeared in places like Religion News Service, Christianity Today, Hidden Compass,Catamaran, Brevity, River Teeth, and Nowhere. Her first book, a memoir-in-essays about a decade in the Middle East, releases from Lucid Books in Summer 2025.