STORY BY HEATHER M. SURLS

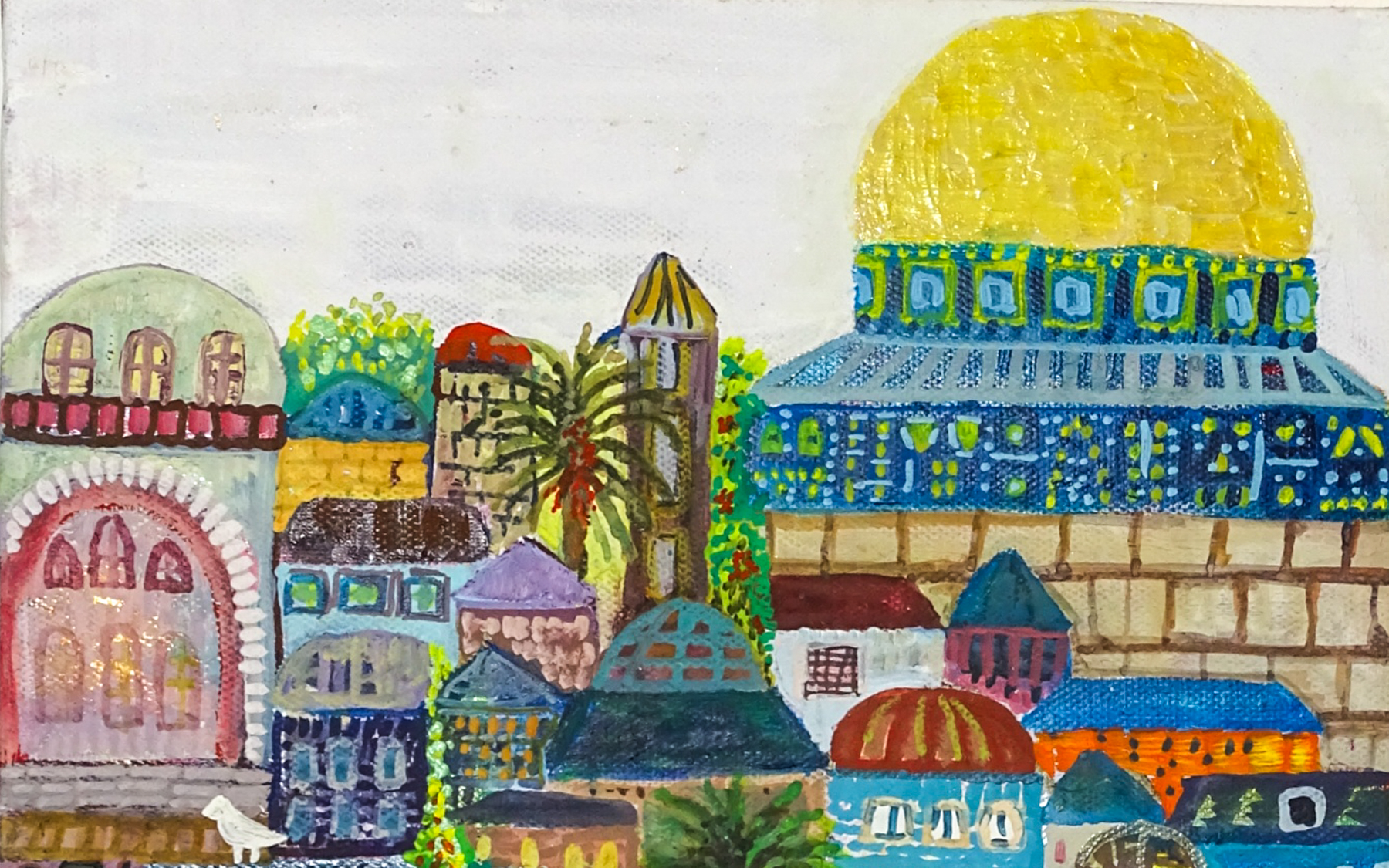

ARTWORK BY HAIFA ABU KHDAIR

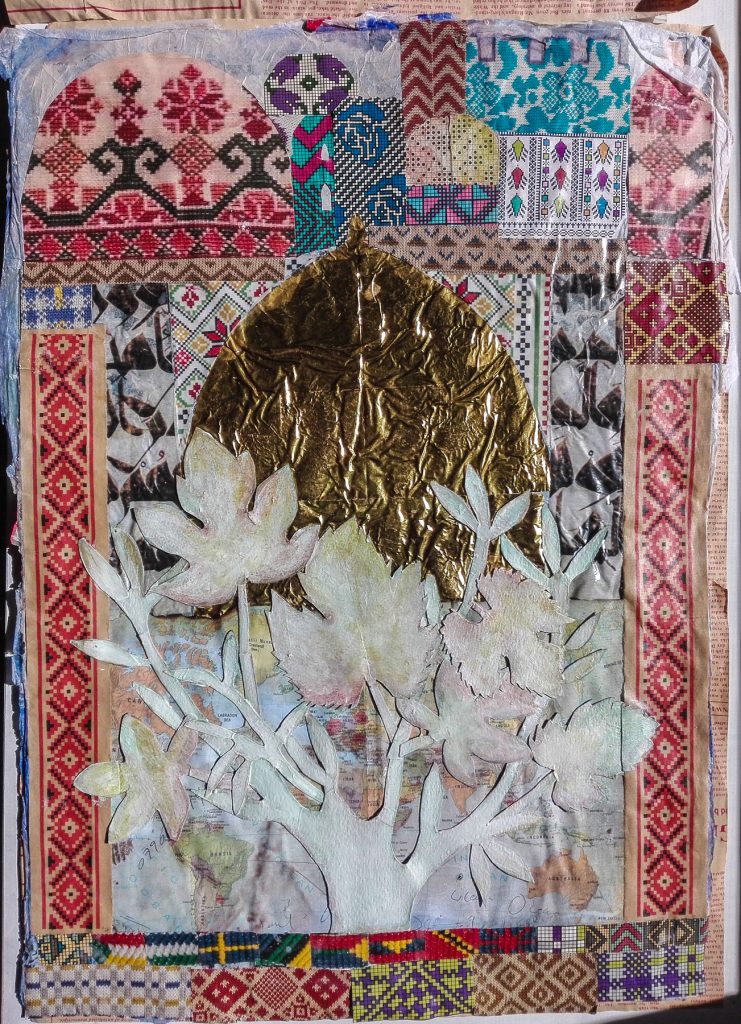

In Jordan’s Baqa’a camp for Palestinian refugees, I sat with several women and piles of their cross-stitch embroidery. A fan blew the late May heat through a simple but neat room, where we sat on brown couches drinking small goblets of juice, followed by Turkish coffee and tea. Zahieh Ahmad Saeed Abu Rases and her relatives showed me embellished pillowcases, a mirror framed in a kaleidoscope of colors and patterns, clocks stitched on white Aida cloth, and sections of unfinished thobes, traditional Palestinian dresses.

Abu Rases—called Um Ahmad, identifying her as mother of her oldest son, Ahmad—wore a long black abaya, and her plain, sturdy face was framed by a tan-colored headscarf. Though she once taught math in Saudi Arabia, when she returned to Jordan, Um Ahmad began working as an embroiderer, stitching hours a day to provide for her five children. Her husband, who lost his eyesight from diabetes and an accident, is unable to work. Right now she’s employed by Deerah, a young Canada-based company that creates customized, hand-embroidered thobes.

“I embroider for the whole world,” Um Ahmad said in her deep voice while showing me her current project, a bridal gown with colorful cross-stitch on white crepe fabric for a customer living in France. After personal consultations with Deerah, in which customers can help design their thobes, the company’s embroiderers spend up to 260 hours stitching a product. These employees are Palestinian women living in the Baqa’a camp, about 12 miles north of Amman, and in the Gaza camp in Jerash, about 30 miles north of Amman.

While, historically, Palestinian women embroidered their own trousseaus before marriage, Um Ahmad said employing her needlework for others has enabled her to pay for her kids’ education. Her oldest son, Ahmad, studied in a Jordanian university and now works as an engineer in Oman. By using skills handed down through generations, Um Ahmad follows in the steps of other Palestinian women who are using their traditional handcraft to support their families while at the same time perpetuating the memory of their homeland.

“Besides the financial benefit, in this way we practice our country’s culture,” Um Ahmad said. “We preserve our identity. This is our culture and heritage.”

When Um Ahmad referred to her country, she wasn’t talking about Jordan, though she was born here, in a village called Karameh, and grew up in the Baqa’a camp, which was established in 1968 after the war with Israel and is now home to about 120,000 Palestinians. Along with more than 2 million Palestinians registered in Jordan with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East, Um Ahmad considers Palestine—the strip of land west of the Jordan River identified on most maps as Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza—as her homeland. Because of restrictive Israeli policies, Um Ahmad has never visited the country, but typical of many Palestinians in exile, she carries a deep attachment to the land, which she describes as “a piece of heaven.”

Though I initially contacted Um Ahmad to learn more about the process of stitching an entire thobe, I was just as eager to hear her stories and perspectives on her identity as a Palestinian woman. And Um Ahmad and her relatives were eager to share—sometimes all of them talked animatedly at the same time, flashing me pictures of embroidery patterns on their phones while dipping in and out of family stories and political issues.

“We want our voice to reach the whole world,” Um Ahmad stated. Her phrasing reminded me of Shireen Abu Akleh, the veteran Palestinian-American reporter for Al-Jazeera who was killed on May 11, 2022, while reporting on an Israeli Defense Force raid in the West Bank city of Jenin. Abu Akleh was treasured by Palestinians because she amplified their voices, humanizing and dignifying a people often misunderstood by the West.

Glad for a chance for her own voice to be heard, Hajr Saleh Arrabaty, a tiny woman in her mid-80s who had lived in Palestine before the state of Israel was established, sat down beside me on the couch right away, her wrinkled face circled by a white, lace-edged hijab. In thickly accented Palestinian Arabic, Arrabaty—called Um Salah—told me she was born in ‘Ajjur, a city northwest of Hebron, in the late 1930s. British Mandate reports from 1945 state that ‘Ajjur’s population was about 3,700, and that the village depended on olives, wheat, and animal husbandry for its livelihood.

Prior to and after Israel’s establishment on May 15, 1948, Jewish military units systematically attacked Arab villages and towns in the area delineated by the 1947 UN Partition Plan as a Jewish state. Unfortunately, they also penetrated into the proposed Palestinian state, using terror tactics to induce the residents of these villages to flee. As a result, around 700,000 Arabs were expulsed from around 400 villages and towns, including the people of ‘Ajjur.

Um Salah said ‘Ajjur’s residents had heard about the massacre that occurred in Deir Yassin, a village near Jerusalem, and since they were unarmed and afraid, they fled under the Jewish forces’ shooting. They walked from village to village, sometimes sleeping on the plowed ground between trees, before reaching Jericho, where they lived in a tent in weather Um Salah described as fire. Eventually, Um Salah and her relatives continued to the Dheisheh camp in the Bethlehem area.

“We lived there, we stayed day after day, month after month, and year after year,” Um Salah said. “We stayed a long time, and we grew up, and we became old women.”

By the time Um Salah married, she had moved to Karameh, a village on the east side of the Jordan River, in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, which gained political autonomy in 1946. She had two children, but both died in infancy. When she was not able to have more children, her husband married Um Ahmad’s sister. After a six-day war in 1967, Israel occupied the Jordan-controlled West Bank, triggering another wave of Palestinian refugees. This time roughly 300,000 people fled to neighboring countries like Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon. After a battle was fought between Israel, Jordan, and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in Karameh in 1968, Um Salah, her husband’s other wife, and the future Um Ahmad settled in the Baqa’a camp.

To this day, 10 official and three unofficial Palestinian camps exist in Jordan, housing approximately 360,000 people. Camp residents originally lived in tents, but these were eventually replaced by prefabricated buildings, and most of those have evolved into cement block structures. Most of the Palestinian camps have been completely absorbed by the cities surrounding them, though their buildings’ shoddy construction and the small lanes between them distinguish them from other areas.

While the UNRWA provides some services to Palestinian refugees, the Jordanian government has full administrative and security authority in the camps. The UNRWA reports that high unemployment and poverty are serious concerns in Baqa’a, but Um Ahmad also told me that everything is available there: centers for young people, companies, malls, restaurants, schools, parks, and exercise clubs. She also pointed out that although refugees in Syrian refugee camps in Jordan, for example, are not allowed to leave the camps without permission, residents of Baqa’a can travel independently and work outside of the camp.

In fact, the majority of Palestinian refugees in Jordan enjoy the full rights of Jordanian citizens. King Hussein, who reigned from 1952 to 1999, granted Jordanian citizenship to Palestinians who were displaced by 1948’s Nakba—Arabic for “catastrophe.” However, according to a Jordanian census conducted in 2015, around 635,000 Palestinians in Jordan do not have Jordanian IDs. Without Jordanian national numbers, they cannot access free public education, health care, and public benefits. The majority of those without Jordanian IDs are Palestinians who were living in Gaza and displaced in 1967.

“In order to preserve Palestinian identity, we don’t give them a national number,” Um Ahmad told me. If these were given citizenship, she explained, the case of Palestinians’ right of return would be weakened.

Palestinians regularly refer to this “right of return”—al-‘audeh in Arabic—which is codified in UN Resolution 194 from December 1948. But for everyday people, al-‘audehis not just legalese. Palestinians consider the right of return a basic building block in any sustainable peace agreement between Israel and the Palestinian people. I once interviewed Ruba Shaheen, a former neighbor and embroidery hobbyist from Jericho who moved to Amman when she got married. While chatting about embroidery, she vividly portrayed the concept of al-‘audeh and its centrality in Palestinian thought.

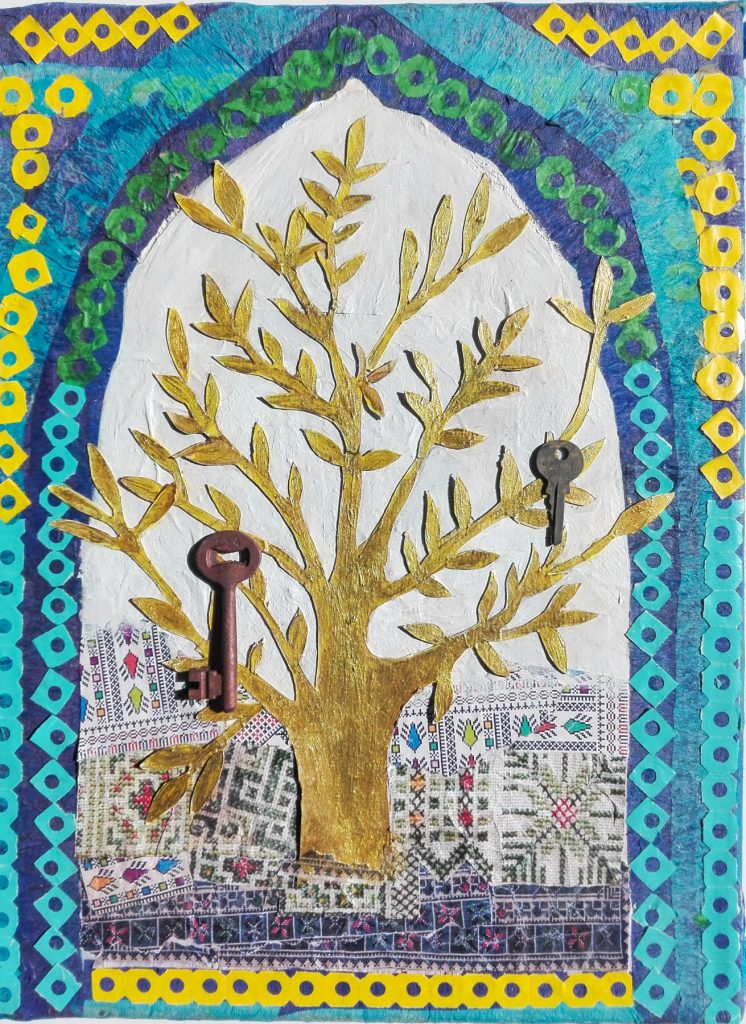

“If you go to the camps where there are Palestinian refugees, you see elderly people. You find they have with them the keys of their old homes. Until now, they are keeping them.” She said that if you express doubt about them returning, these older people will reply: “It’s impossible that I will abandon my country or my land or my house. I may one day return there.”

“They’re holding on to the hope of return,” Shaheen elaborated. “They say, ‘One day, certainly, we will return. Of course we will take back our land. Of course our land will be liberated.’”

If and how thousands upon thousands of Palestinians realistically could return to their ancestral land is a matter of debate, one that requires nuanced investigation of a conflict that continues to develop day after day. While Western media outlets tend to headline stories from Israel and the Palestinian territories when Israeli citizens are wounded or killed, they largely ignore weekly, and sometimes daily, injustices incurred by the Israeli government and security forces on the 5 million Palestinians in West Bank and Gaza.

As a resident of the Middle East, I follow Arab news alongside Western outlets, so I’m familiar with Palestinian grievances against Israel. In the Baqa’a camp, Um Ahmad and her relatives listed some of these: Palestinians killed by radical Zionist settlers; Palestinian minors arrested and/or killed by Israel Defense Forces; homes demolished; settlements built in Palestinian areas, which are generally recognized as illegal by the international community, barring the US, since these are areas reserved for the proposed Palestinian state; and police-guarded extremist groups disrupting historic status-quo agreements on Jerusalem’s Al-Aqsa mosque compound. In the Gaza Strip, 2 million people live under blockade, with sporadic electricity, a dire lack of medical supplies, no travel without Israeli-granted permits, and restrictions on imported building materials to repair damage done by wars with Israel.

Because of these constant provocations, many Palestinians carry deep generational trauma coupled with a passionate nostalgia and persistent sense of displacement. However, through decades of collective suffering, they have also developed deep resilience and steadfastness, promoting their heritage through handcrafts like embroidery and passing on their family narratives to generations who have never seen Palestine, except in the haze across borders. Unlike refugees of other nationalities that I’ve met in Jordan, who tend to look forward to immigration to the West, most Palestinians doggedly hold on to their origins.

“We hope that we will all return to our land,” Um Ahmad said, “that all Palestinians will be gathered in Palestine.”