Sarah Racine during an art therapy session with children living in a slum outside Pune, India.

ARTICLE BY HEATHER M. SURLS

PHOTOS BY SARAH RACINE

Over the last decade Sarah Racine has worked internationally as a trauma-informed art-maker, helping a spectrum of individuals—from victims of human trafficking to refugees—find healing from trauma, abuse, and war. Though Racine calls Lancaster, Pennsylvania, “home” in the U.S., she recently relocated to Amman, Jordan, to study Arabic and explore options for working long-term in the region. Racine sat with Anthrow Circus’s Jordan correspondent, Heather Surls, to talk about her profession and how the arts can bring healing and hope to adults and children affected by trauma.

HS: Art therapy seems to be becoming more common these days. Can you define your field for us and tell us what trauma-informed art therapy or art-making is?

SR: Art therapy uses different creative mediums to help process traumatic events, and one of the reasons it’s becoming so popular is it has a lot to do with PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder], so it really helps people who experience that. It provides an outlet when words fail, and it creates safe spaces to express past experiences that might be hard to speak about. It’s a way that engages a different part of your brain, that allows you to share difficult memories. The “trauma-informed” aspect of it is based on principles of safety, transparency, choice, collaboration—because healing happens in relationships—and empowerment.

HS: Practically speaking, how does art therapy enable people to recover from trauma? What happens in your brain—psychologically, physiologically?

SR: Art therapy is a bridge from the unconscious to the conscious. It has an ability to reveal what’s underneath the surface. It engages a different part of your brain, the amygdala, which is involved in controlling the emotions, and where emotions, fear, all of that, are contained. This part of your brain can be greatly impacted by stress, and it tries to protect and guard you by burying memories, basically. Art therapy is a way to engage that part of your brain. It allows you to engage them in a way that helps process them more clearly without creating more damage. The idea with art therapy is that you’re telling your story once-removed, so it doesn’t make it as dangerous. By putting their stories on paper, individuals can see the emotions, and therefore, it’s easier for them to communicate about things they experienced.

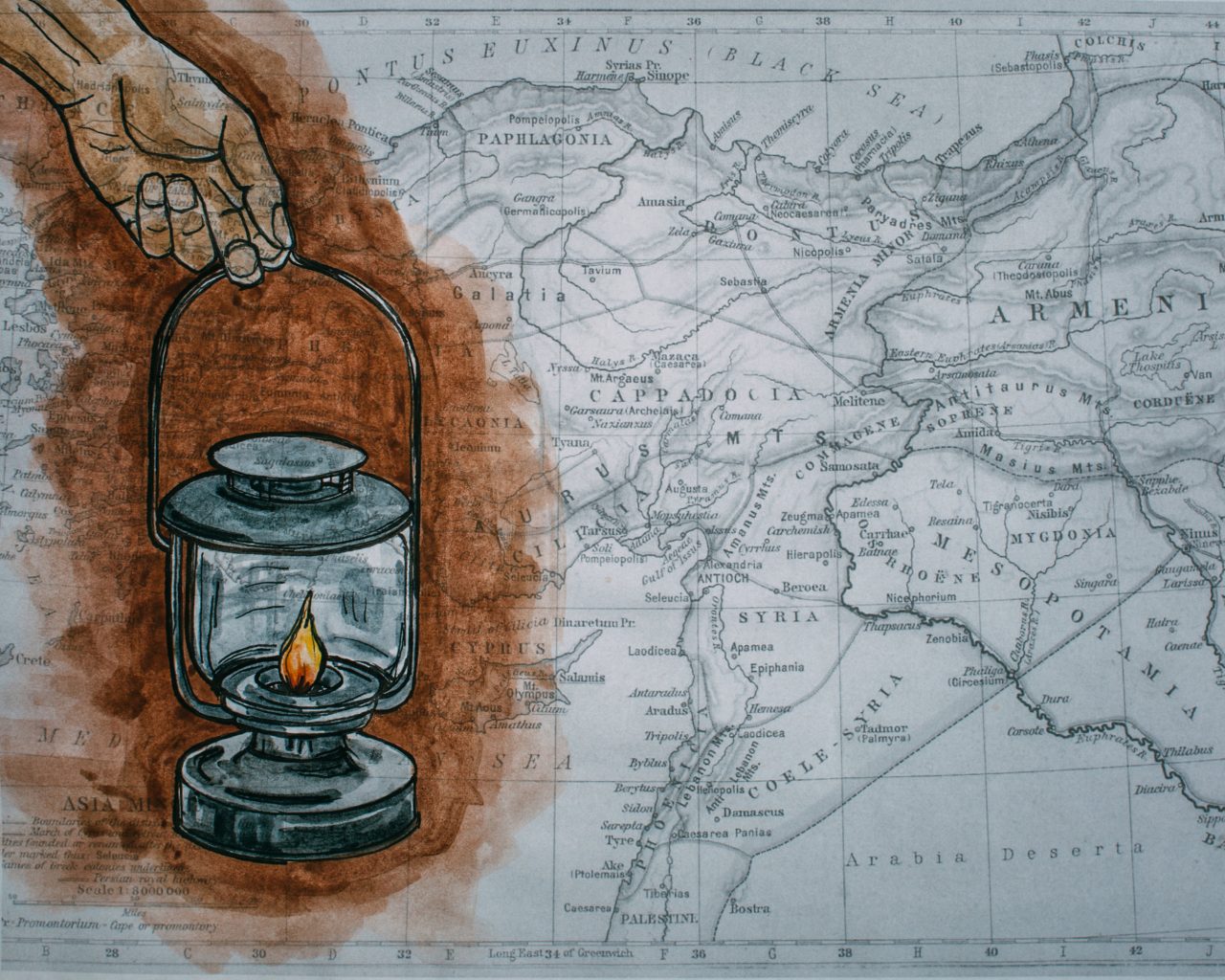

Be a light among the nations. Sarah created this piece to help process what she witnessed during her year in Moria refugee camp on Lesbos Island, Greece. The camp was such a dark place in great need of hope, life, and light, she says.

HS: Can you tell me more about how you got interested in this field? Did you have any personal experiences with art therapy that drew you to enter this area?

SR: The main reason that I was interested in this field was because of a past experience. When I was about five or six, my parents divorced, and they had my siblings and I go through counseling sessions after the divorce. I had a hard time actually talking about what had happened. Unfortunately, my birth dad was very physically abusive toward my mom, and I had seen a lot of that. I witnessed the fights and the hospital visits, and I had buried that and didn’t feel very safe or comfortable to speak about it.

They ended up bringing crayons and paper to me and had me just start drawing. And it felt not as invasive. As a child you want to please, you don’t want to get anyone in trouble. This way it was more of an opportunity for me to express something that I just didn’t have words for at the time. That was my first experience with art therapy, and I saw how impactful it was in my life.

Growing up in school, I was always very much attracted to drawing. Even in class, doodling would allow me to engage and retain information. I thought it was fascinating and wanted to look at how that could help people. So that is what got me interested in the beginning, and I’ve been able to see how it can create safe spaces for victims of trauma, abuse, trafficking, war, and how it has allowed them to process past hurt, pain, and also restore and redeem and give them tools to help as they continue to deal with PTSD.

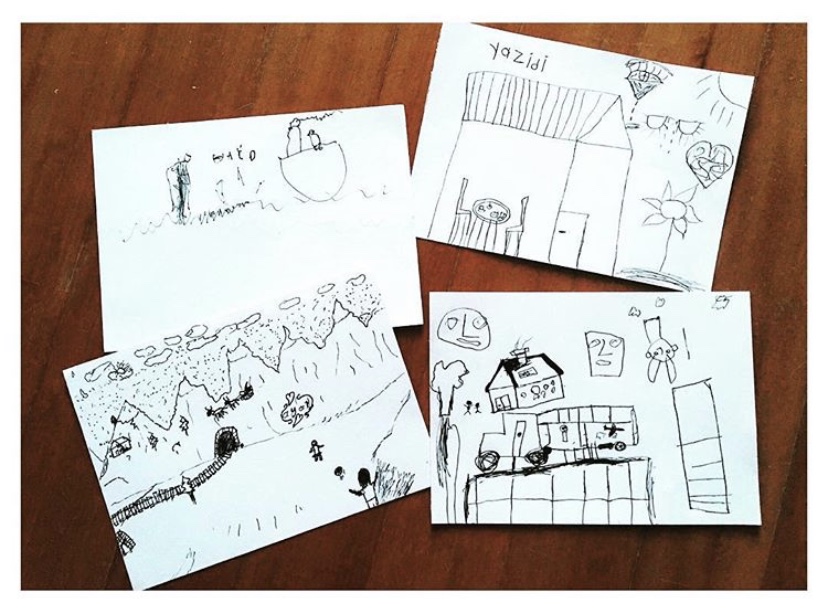

This artwork by Yazidi children in Moria refugee camp depicts fleeing from war and life on the sea as they escape to safety.

HS: Share with us more about the places you’ve gone and some of your experiences.

SR: I’ve traveled a fair bit in the past few years, mainly in Southeast Asia—Cambodia and Thailand— Kenya in Africa, in a refugee camp in Greece on Lesbos Island, and the Middle East region, including northern Iraq. My heart is to empower locals to do trauma-informed art-making or to understand these types of practices, because I know that they will be able to engage their own land and people better than I can.

From the time I graduated college in 2009, I had a desire to understand different cultures. I was fascinated with the world outside my American borders and wanted to really come against social injustice—like trafficking, the refugee situation, children of war, child soldiers. I really wanted to pour my resources where there was the most need. I saw that America was congested with therapy. As soon as someone needs a speech therapist, a counselor—all of those are at your fingertips in the States. The same situations are happening overseas, but there’s not as many people who know or are empowered to do things like this. So mainly why I’ve done it overseas is because that is where I’ve seen the most need.

This Rohingya grandmother in Kutupalong refugee camp in Bangladesh remains stateless.

HS: Can you share a few stories about people you’ve worked with who have benefitted from this kind of therapy?

SR: I have a lot of different stories, but one that really sticks out is in Southeast Asia. There were these girls who’d been trafficked; they were in their early 20s. And in Cambodia, also there’s the war that happened in the ‘70s, where there was a massive genocide. You not only had this trafficking situation—these girls who have dealt with sexual abuse, with slavery, being sold by their own parents—but you also have culturally a dynamic where these individuals have a deep hatred of themselves—the way they look, even just their presence on earth.

The dynamic with art therapy there was very fascinating to me because things that would translate in the States didn’t necessarily translate there. You have to really look at issues that are coming up because of trafficking, but also what are the cultural issues. Identity seemed to be the issue we needed to deal with, their self-image. I started with empowering the girls with simple lessons and techniques about how to draw, because sometimes you feel like you can’t really represent what you want because you don’t know how to draw. Each week we’d have a lesson on identity, or I would ask them their thoughts on what is beautiful. It was a four- or five-month process of just looking at identity and an ability to see themselves as worthy, as beautiful, as humans, as ones who have a hope for their future.

An Indian child Sarah met while doing art therapy with women and children in the slums outside of Pune.

In Greece, I did a lot of more informal art therapy, because there you have people who would come for maybe a few weeks, a few months, maybe a little bit longer. It could be as simple as, “Draw me a picture of how you got here.” I did that with children and women, and a lot of the images, it’s very disturbing for us, but for them it’s the norm. We really tried to help them process, even just telling their story. That was a hard season. How do you give them hope for the future when you don’t even know what that could be for them? In America, I can ask a woman, “What are your hopes and your dreams?” and most of the time we can articulate that, whereas in the Middle East, sometimes their hope and their dream is just to have a stable place to live or a roof over their head. Depending on culture, and depending on what they had experienced, you really have to find ways to navigate and have the right questions and questions that will translate well.

“By putting their stories on paper, individuals can see the emotions, and therefore, it’s easier for them to communicate about things they experienced.”

Sarah Racine

Ruth went through the Neema program in Kitale, Kenya, and is now a shop manager. She has hope for her daughter’s future and for helping other women who have been raped and abandoned by men.

HS: Are there kinds of people who would benefit more from art therapy, and types of people who don’t?

SR: To be honest, I can’t personally think of anyone who wouldn’t. I think if someone is closed-minded to the idea of it, it possibly could not be for them. A lot of people think it’s just for children, but it’s definitely proven extremely vital and helpful for adults as well. It’s not just for trafficked victims, it’s not just for refugees. It’s not just for those big social issues. I think it’s a great way to integrate with counseling that can be for anyone. I think it’s for all ages and all walks of life.

HS: What art mediums have you used with people in their therapy? How do you choose which to use? What are some other examples of artistic or expressive mediums that therapists use?

SR: My training is specifically in drawing and painting and photography. I love using those mediums because they’re very practical tools. You don’t need a lot of resources—a crayon, pencil, if you can get ahold of colors. When it comes to resources and doing it overseas, those seem to be the most easily accessed tools.

I love photography. I love empowering people with a tool that they can go out and create, capture their lives, capture what’s around them. I’ve seen music therapy, writing poetry, play therapy, drumming, dancing—the arts in general. It really all just depends on the person. I try to do assessments—who’s the client, who’s the participant, what are their needs, things they’re trying to work through.

While volunteering in Moria refugee camp, Sarah met Laity, an Iraqi boy whose left side was burned during the war.

Saif, a single man fleeing from fighting in the Iraqi war when Sarah met him in 2016, has since resettled in America and is married with a child.

“One thing I love about Sarah that didn’t come up in the interview: she is so slow about getting her camera out. She really believes in understanding a culture and gaining people’s trust before photographing them. When she told me this, she’d been here already three months and still hadn’t unpacked her big, non-phone camera.”

Heather Surls

HS: As a practitioner of art therapy or art-making, you are exposed to a lot of secondary trauma. How have you used art therapy on yourself?

SR: Secondary trauma is very common and is discussed a lot, especially with people who engage in this specific area. I always encourage practitioners themselves to get counseling, whether that’s once every other month or a few times a year. In Greece, I had a counselor I met with, sometimes almost weekly, because the stories you hear, it’s just heart-wrenching and sometimes you lose sight of hope. I’m a burden bearer, and I realized if I’m not healthy and I’m not processing these things myself, I find myself getting in the same headspace as these people are dealing with. It’s like PTSD.

I love to draw as my own therapy. I definitely try to integrate that within my weekly routine. It’s also a way for me to express stories I’ve heard and to create awareness of what’s going on. I’ve definitely used that in my own life, to not share personal stories, but to share a general social injustice or issue, whether it’s war in Syria, child soldiers in Uganda, trafficking in Southeast Asia. The arts have been really helpful for me navigating and processing those things that I’ve seen and experienced.

HS: What are your dreams for working in this area in the future?

SR: My dream and my hope is to be planted within this region long-term because I do see a major issue at hand with the refugee situation. And I don’t see that going away anytime soon. While I was working in the refugee camp, there was only a handful of psychologists who were able to give some kind of space for refugees to share what they were experiencing. I think with art therapy, it’s such a unique way for this specific people group to receive healing, restoration, hope for their future. So my dream is to stay planted here so I can continue to engage with them, in helping them process what they have seen and experienced. I would love to have a base here to continue to do workshops or help train locals to do this. My hope is to see them feel empowered and their voices to be heard. My hope is to see them receive the same type of healing that I was able to receive, that this experience would not dictate their future and that it would not keep them in bondage. My desire is to see them thrive, not just surviving day to day.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. To learn more about Racine’s work, visit her website.

In addition to serving as Anthrow Circus's assistant editor and proofreader, Heather Surls regularly contributes stories to the site, drawing inspiration from her relationships and experiences in Amman, Jordan. Her reporting and creative work have also appeared in places like Religion News Service, Christianity Today, Hidden Compass,Catamaran, Brevity, River Teeth, and Nowhere. Her first book, a memoir-in-essays about a decade in the Middle East, releases from Lucid Books in Summer 2025.