First Street, Snohomish.

STORY BY RICHARD PORTER

PHOTOS BY JAKE CAMPBELL

There’s a place in the popular American imagination called Main Street—a Norman Rockwell scene where the butcher, baker, and barber all hang out their signs and sweep their stoops, where emerald baseball fields are immaculately groomed, and where the town gathers on a Friday night to cheer the high school football team to victory.

If this vision of the idyllic Main Street America is flawed, it’s because it’s based on a nostalgic vision of the past that rings dissonant when compared to the reality that many Americans face today, especially amidst a global pandemic: a shrinking economy, a housing crisis, outdated infrastructure, and political division.

But if a place like Main Street America does exist, it probably looks something like Snohomish, Washington.

Snohomish, population 9,875, is a small town 40 minutes north of Seattle with a literal main street called First Street. This highly walkable, four-block strip runs parallel to the lazy Snohomish River. The river valley is lush and green, filled with farms and barns that double as wedding venues. From spring to fall, hot air balloons rise out of the valley and local wine club members convene to sample Washington-grown vintages.

First Street in Snohomish is lined with shops, bakeries, restaurants, plant stores, and small businesses. The city planners of yesteryear had the foresight to zone the city to forbid fast-food restaurants and strip malls in the downtown core. Highways don’t touch the heart of the city, and, indeed, the local economy thrives on its … well, its Main Street-ness.

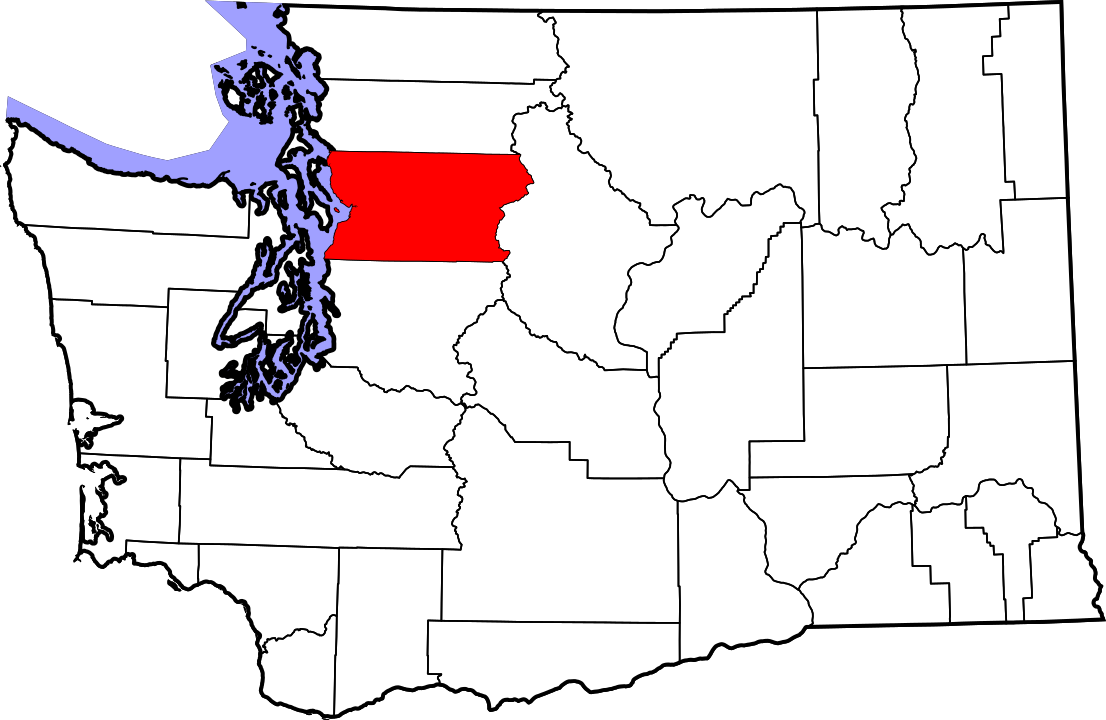

Location of Snohomish County, WA

Photo provided by Wikipedia Commons

Snohomish has done what many small towns have been forced to do: It’s reinvented itself through marketing and harnessed the forces of gentrification. Old buildings that once held greasy diner cafés and car repair garages now offer shopping opportunities for Seattle tourists making day trips to the river valley. Downtown has become a place to linger over a croissant, window shop, or search ritzy boutiques filled with upcycled, rustic chic furniture. On an autumn day in Snohomish, you’ll find professional photographers taking portraits of high school seniors leaning against brick walls or sitting confidently in the whitewashed bandstand that overlooks the river.

This is small-town America. Yet increasingly, residents of Snohomish and other local populations are divided over what their vision of small-town America entails. This year that division increased and tension built as residents squared-off on social media and began to wage an escalating culture war that took no prisoners and found little room for compromise or moderation.

How did idyllic Snohomish get here?

This year…division increased and tension built as residents squared-off on social media and began to wage an escalating culture war…

“If the town has an Andy Griffith feeling, it’s partly because preservation-based economic development is the town’s whole thing.“

Here’s the thing about Snohomish: Despite all its reinvention, it’s somewhat trapped in the past, for better and for worse. Tellingly, it’s known and marketed as the “Antique Capital of the Northwest.” Part of the town’s marketed identity has rested on its collection of curated antique stores, which bring tourist dollars to the local economy.

Tourist dollars weren’t always the economy’s driving force. For almost a century after its founding in 1859, the city of Snohomish was a working-class town. People who lived here had jobs cutting shingles or plywood at riverside lumber mills or punched the clock at places like the aerospace giant Boeing in the nearby city of Everett.

Then, in the late 1970s and 80s, both the federal government and Washington State passed new environmental regulations that put a halt to the timber industry. Snohomish’s mills shuttered for good. The city had to pivot to stay viable. So, it became a tourist beacon.

And, seemingly, people liked the new version of Snohomish. It’s cute, alright. It’s Beaver Cleaver.

If the town has an Andy Griffith feeling, it’s partly because preservation-based economic development is the town’s whole thing. The small-town vibe is an economic model, one which feeds into other facets of the local economy: agrotourism attractions, like pumpkin patches and corn mazes, and the wedding industry, which makes use of rustic barns and provides bread and butter to wedding planners, photographers, florists, and caterers. Folks come here for the beauty of feeling like they’ve traveled back in time—and some people live here for the same reason.

Fast-forward three decades to 2020. Last summer, when present-day America came to the antiquated town of Snohomish, conflict was bound to break out.

In late May, after the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, cities around the country were filled with protesters who marched against police brutality. In Seattle, protests reached a fever-pitch. Protestors threw Molotov cocktails, broke into stores, and set police vehicles on fire.

The Seattle protests, still escalating in late May and early June, were seen by many Washingtonians, particularly those in rural areas, as acts of extremism. The protests that took place in smaller communities like Snohomish were peaceful. Protests here were comprised of several dozen citizens wearing masks and social distancing while waving homemade Black Lives Matter signs at passing motorists.

But in the last days of May, tensions escalated online. Several right-wing groups claimed they found reports of Antifa action in Snohomish (these reports were investigated by local media and remain unconfirmed). In response to rumors of leftist looting coming to Snohomish, these right-wing groups, in closed social media groups, made plans to converge on downtown Snohomish and “protect” small businesses with guns and their presence.

Fast-forward three decades to 2020. Last summer, when present-day America came to the antiquated town of Snohomish, conflict was bound to break out.

On Sunday, May 31, about 100 armed men, forming a loose militia, showed up on First Street in Snohomish. Reports mention at least one Confederate flag flying from a truck. The atmosphere was like a tailgate party as armed men drank beer on the street in the presence of the county sheriff, who did nothing to stop them. Local media photographed some of these militants making racist hand gestures and wearing body armor with Proud Boys patches. The next day, Monday, June 1, a cell phone camera captured video of a man punching a protestor, a teenage boy, in the face as he marched with a crowd in downtown Snohomish, chanting that black lives matter.

After watching videos of the armed counter-protestors, I’m left with a lot of questions. What were these men with guns afraid of? What were they afraid of losing? What threat did they perceive in a bunch of teenagers walking down the street?

How do people, on both sides of the political spectrum, get so scared?

“Fear divides—but it can also unite us as a society to achieve a common goal.”

The aftermath of last summer’s tension in Snohomish has been, well … anticlimactic. Racial tensions have been subsumed by larger worries about the coronavirus and its effects on the small businesses that constitute the downtown core of the city.

During my reporting for this story in late 2020, I spoke with a member of Snohomish’s downtown business bureau. She said that her organization was still struggling to do PR work—to spin the story that their small town is a place where black lives matter, to counter the image that Snohomish is synonymous with overt racism, public drinking, and the brandishing of long guns on street corners.

The town’s mayor, John Kartak, has to date refused to condemn the right-wing militia members who gathered on May 31. He downplayed their actions on local AM radio interviews. During a city council meeting in June, which happened through Zoom, locals took turns criticizing Kartak’s lack of response. Residents and community leaders who perceive his stance as supporting racism and white supremacy have called for his resignation.

At the time of this writing, in early December, Washington State is in the midst of a second wave of the coronavirus pandemic. Local cities are in lockdown, with restaurants operating at 25 percent capacity. The main street in Snohomish is lined with rows of tents wrapped in plastic, made somewhat cozy amidst the Northwest’s damp winter chill by space heaters. These booths are for dining “al fresco” during the pandemic. To me they look something like the hazmat tents in the movie E.T. While the tents allow diners to eat in relative safety, the idea of eating in a plastic bubble as winter sets in seems to be unnerving. Local restaurants are hanging on by thin profit margins. People are tense.

What’s ahead is a dark winter as the city, and the nation, wait for a vaccine that, when administered, will hopefully turn the nation back to normal. But what is normal? And how can we go back to it, after the stresses of 2020 have revealed dark and violent forces in our midst? America, from Main Street to Pennsylvania Avenue, is still figuring that out. We think about it in the isolation of our homes. We debate it on social media platforms with posts and memes.

How do people, on both sides of the political spectrum, get so scared?

Cities change because cities are made up of people. Sometimes they take decades to slowly transform their economy. Sometimes radical social shifts happen seemingly overnight. This can be jarring for some.

Ultimately, I have to believe that opposite opinions and beliefs can be peacefully resolved. I have to think that hatred is based on fear. Fear divides—but it can also unite us as a society to achieve a common goal, as it did during World War II.

I want to believe the best about Snohomish, Washington. I want to hope that the past can inform the future and that the present is the crucible in which the best version of ourselves can be formed.

That’s the Main Street I want to visit: a place where national adversity motivates change, both collectively and personally, for the better.