STORY BY HEATHER M. SURLS, WITH TRANSLATION HELP BY MARADI AYED ALHAWARI

PHOTOS BY HALA MAHMOUD

Our resident correspondent in Amman has been working on this story for ages. As she ran into road block after road block, we thought we might have a mysterious mini-series on our hands, complete with legends, cracked-open doorways, and classical Arabic to decipher. But our intrepid writer persisted and now brings you a delicious story of the power of a multi-generational love affair with books.

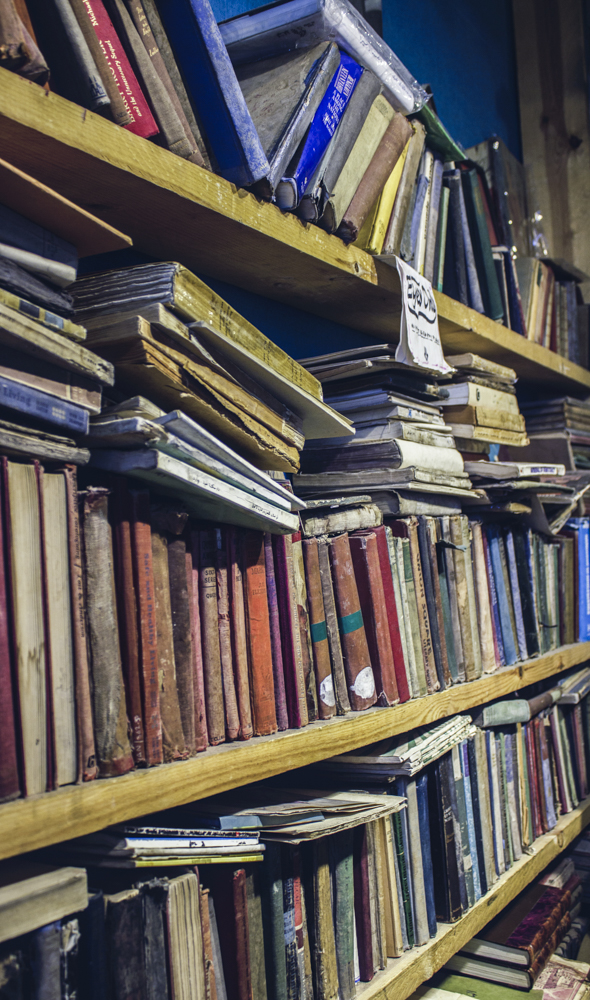

The Mahal al-Maa bookstore in Amman, Jordan, explodes from its 50-square-foot space, spilling onto the sidewalk where it fills shelves and wooden crates beneath a striped canopy.

Selling books is Hamzeh al-Maaytah’s calling. He believes in books. Even though he’s married and has five children, he often sleeps on a mattress in the back of his store, making himself and his books available to customers 24/7.

“Books are like medicine,” he says, “or more dangerous than medicine, and their effectiveness is stronger, because they have ideas. And ideas are a problem.”

Hamzeh and I sit in his shop, somewhat distanced from the noise of Quraysh Street, a main thoroughfare in the balad, Amman’s old downtown. Wearing jeans and a Cat-in-the-Hat T-shirt, Hamzeh looks casual. But his constant immersion in literature affects his speech; instead of speaking the Jordanian dialect of Arabic, his stories and ideas are laced with Fusha, the classical Arabic used in any printed medium but normally not used in spoken conversation. In my three years in Jordan, I’ve never met someone who talks like this.

Medicine is not the only thing Hamzeh compares books to. Books are like boats, he says. Some can keep people afloat, while others make them drown. Books are like food for the mind. Books are like water. In 2016, Hamzeh actually renamed his shop “Mahal al-Maa”—“Water Shop”—to reflect the necessary nature of books, and specifically of good books, which help people develop in positive ways.

“Water is free,” he says. “Every person needs water, and books also are like water.”

This isn’t a meaningless platitude for Hamzeh either. He refuses to put fixed prices on his books, because he does not want cost to hinder anyone from reading. One of his shop’s trademarks is his exchange policy, which he says has caught on with other booksellers in Amman: after paying the price of a book, a customer can return the book and pay a dinar (around $1.40) to exchange it for a new book.

Even if the shop is closed, he says, his books remain outside, available to customers, who can leave their dinars in a drop box. Making money is not the goal, he says. Reading is.

“Books are like medicine…or more dangerous than medicine, and their effectiveness is stronger, because they have ideas. And ideas are a problem.”

Meeting Hamzeh is a personal victory. I first heard of his 24-hour “emergency room for the mind” in fall 2017. On my first attempt to meet him that fall, I discovered the Amman Public Library, but not Mahal al-Maa. A few weeks later, following signs in Arabic and English, I located the ruins of the Roman Nymphaeum, supposedly next door to the bookshop. I found only several dusty, bright turquoise bookshelves on the sidewalk and a metal door rolled down and padlocked.

After emailing the bookstore to confirm its location, I tried visiting a third time. The door was open just a crack. I knocked tentatively. Was Hamzeh sleeping inside? Should I ask the men at the barber next door? In the end, I bowed to what seemed the more culturally appropriate action and didn’t push further when no one responded to my knock.

But in January 2018, Mahal al-Maa was still on my mind. Partly it was the bookstore’s history that drew me. Hamzeh inherited his livelihood from his father, Mamduh, who inherited the shop from his father and grandfather. In 1948, Mamduh moved his books from Jerusalem to Amman when thousands of Palestinians fled their homeland. He set up Al-Jahith’s Treasury, the first lending library in Jordan. (Al-Jahith was an eighth-century Iraqi writer who reportedly died when a stack of books fell on him.) When Mamduh died in 1993, three of his seven sons—Hisham, Hamzeh, and Muhammad—inherited his work, setting up shops in three locations in the balad.

So I emailed Hamzeh again. He made a confession: “My English is very weak. I am writing to you through Google translate.” I replied in Arabic, pecking the stickered keys on my keyboard. Don’t worry. I speak Arabic, and I will bring a translator with me. We set an interview for that Saturday morning.

The day before the interview, I watched a video of Hisham, the brother who runs a well-known book kiosk near Mahal al-Maa, describing a fire that had recently destroyed thousands of rare books and manuscripts in the al-Maaytah brothers’ warehouse. I felt surprised that Hamzeh hadn’t mentioned this to me; it seemed such a loss.

I told my translator to meet me by the Husseini Mosque at 9:45 on Saturday morning. When I arrived, I planted myself in a sheltered corner and waited in the rain. I smelled falafel, crispy as it came out of the fryer. Shopkeepers squeegeed rain away from their storefronts and into the street. The marble plaza in front of the mosque shined.

My translator never showed up. I texted Hamzeh to apologize. “I waited for you,” he wrote, and sent me a picture of the wet street, a mourning dove in the corner.

A couple months later, Hamzeh’s brother Hisham died in a car accident. I texted Hamzeh the appropriate condolences, then ended with a question: What will you do? Three days later, Hamzeh replied with a tiny block of words:

سلام يا هيذر

ساعمل سلام

Peace, O Heather,

I will make peace.

I wanted to ask him what that meant—what does peace mean, O Hamzeh? What would peace look like for you? But I read sadness in his words, the grief of a man who had lost much. I chose not to pry into his grief, and with my unanswered questions, I sat in silence.

Until today.

Outside the shop on this Saturday morning in September 2018, about a year after I began pursuing this interview, a mama cat and kittens wrestle among Hamzeh’s books. While I sip the coffee Hamzeh brought me, I ask about January’s warehouse fire. The news made it out bigger than it was, Hamzeh tells me. Yes, a lot of books burned, but they were mainly new books and copies of the Qur’an, not old manuscripts as had been reported.

I ask about Hisham’s kiosk, how it’s operating after his brother’s death. Hisham’s sons are running it, Hamzeh says, and Hamzeh is coaching them in bookshop administration. Since Hisham’s death, he adds, his other brother, Muhammad, has started working with him at Mahal al-Maa, bringing Hamzeh some much-needed work-life balance.

I also ask about the crowdfunding campaign set up in 2017 to save Mahal al-Maa. Hamzeh lights up as he talks about Alan Elbaum and Hussein Alazaat, friends who helped him set up the Indiegogo campaign that raised close to $19,000. With this money, he was able to pay off thousands of dinars in rent and personal medical bills. With his debts taken care of and his health improved, Hamzeh was able to renovate the shelving in his shop and on the sidewalk and install the striped canopy outside. He dreams of licensing Mahal al-Maa as an organization so he can enter prisons and refugee camps to bring life-giving books.

Hamzeh also tells me about his father, Mamduh, who taught him to love reading. He kept a locked cabinet in their home, full of books. Hamzeh remembers standing in front of it as a boy, longing to get at the books inside, but Mamduh said it wasn’t yet time. Instead, he and Hamzeh’s mother read stories to Hamzeh and his siblings, with acting and singing. They put an alphabet chart beside Hamzeh’s bed.

“I’d wake up and see it, sleeping I’d see it, waking up in the night I’d see it,” he says. “Night and day, the letters were in front of me, taped on the wall. And stories were everywhere—in the bathroom, stories; in the kitchen, stories.”

Though Hamzeh considers the personal library as important to a home as the kitchen, he recognizes that worldwide, reading is under attack. Technology is not a problem, he believes, nor is reading from phones or tablets, but it does prevent people from remembering what they read. The internet is not a problem in itself, but dependence on it is. People used to memorize, but now they use hard drives to store knowledge.

“How will we now preserve this human inheritance?” Hamzeh asks. “We have to return to reading books and reading in general.”

And how could a bookseller and reader like Hamzeh not talk about his favorite book?

“Always the best book is the last book,” he says. “I feel sorry and sad when I finish a book, because I lost people I lived with and their ideas and adventures, and they died—they died in the novel and in my memory. I’m sad. I want to hold a funeral and have people comfort me. So how do I comfort myself? I look to books.”