STORY AND IMAGES BY EJ BOWMAN

There are parts of me

I only recognize from photographs.

—Sarah Kay

La Nonna’s name was Jone Corti then. Jo-ne. It slid off the tongue like a berry gelato. It was strange to burden a young Italian girl with a Greek name, especially one that referred so specifically to Ionia and the adjacent sea. It annoyed me when her biddy friends mispronounced it, suffering the harsh J instead of the more lithe Y.

She was boisterous at 70, kept exotic cacti in terra cotta bowls on the porch next to bleached statues of Tahitian demigods. When I was small, we lived together on Clover Spring Road in the cedar house with the great, east-facing bay windows, a perfect space to watch the sunrise over the still oaks in the summer. Jone collected stories as she collected thimbles and silver spoons, each laid in a black velvet case and tied with a length of green ribbon. I polished each spoon carefully and modeled the thimbles 10 at a time so I could click them together with my fingers.

We three children were a perfectly paired grouping, triply isolated: residents of a diminutive California town, schooled at home, the only Italian immigrants we knew. When we hurt our feet on sharp corners, we called vacca miseria, which was Jone’s favorite profanity. Christmas meant panettone and chocolate coins in our shoes. I was 17 before I learned that cachi were called persimmons.

The sunspots on Jone’s skin, purple and dark brown, rose and fell over deep wrinkles. I wondered many times at her deformed toes and fingers, knobby and knotted and too short for her limbs. A gift, she said, from the war. She spoke English with a thick accent, almost all vowels, but she also enjoyed the small celebrity afforded her as a consequence of her otherness. She joined the Rotary Club, worked for the census, ran the summer concert series at City Park. She dragged me to the knitting circles at Annie’s Yarn Stop, where she could gossip with her friends as they puzzled over patterns in hushed voices. In the spring she smelled like turpentine and linseed, and her counters were piled with books on the Old Masters; on her easel she replicated not only the tempera but also the temperament of the Dutch Renaissance. I learned Girl with a Pearl Earring, Joseph the Carpenter, and Mademoiselle Rose first at her kitchen table, on canvas, still wet and alive and quivering.

Jone told me stories about 27 Via Lomazzo in Milano, where she had lived in the 1940s. There in the apartment building’s latticed courtyard the children played while the voice of Mussolini—Il Duce—streamed in over the radio from 4 to 6 p.m., at which time gatekeepers Carolina and Leonardo shooed them home off the cobblestones.

During the war, ration cards allowed for a liter of milk per day for children, served with one hundred grams of black bread, cut with marble dust to add weight. (After 1945, thousands would have their appendixes removed.) Once a week, the children were issued stamps for a treat from the bakery, which was otherwise empty since there was no flour left to bake.

The first bombs came in October 1942. Jone and her mama, Ines, were visiting in Nigra Square when the alarm sounded and cousin Ruggero came running. The first house was destroyed, then the bakery. On the fractured stairs they passed Swiss friends with bicycles hoisted over their shoulders. The Swiss would sleep outside since they were too afraid of the buildings. My grandmother did not own a bicycle.

Radio London passed messages in code: Tonight the moon is red and John takes water to the mill. Nonsense but great fodder for children’s play when they hid together in the basement during the raids. Ines made a lanyard for Jone’s identification and packed her cardboard suitcase with a few biscuits, two pairs of panties, socks, and a gray wool sweater.

Remember Giannino, brother of Mariuccia who lives in Turate? Jone asks me from a distance. I don’t answer. He was dead 40 years before my birth. Giannino, he was caught and bring to Villa Triste, tortured. They make him empty.

He had a cat and every day at 4 o’clock, this cat leaves and walks for two kilometers to Geranzano where Giannino was used to arrive by train. If the train was late, the cat sit on the bench of the station and wait. Everyone knew the story of the cat, and when Giannino die, the cat still go out at 4 o’clock. How you explain war to a cat still waiting for Giannino? Miseria.

It was with Jone that I learned to make pasta, pounding out the dough before pressing it and leaving it to dry on a checkered tablecloth. When I was little, I preferred chiacchiere, fried strips in powdered sugar like twisted ribbons that clung and clotted on my fingertips. When I was older, she taught me gnocchi, pollo milanese, and carbonara with raw eggs and parsley, my garbled recipes in mixed English and Italian metrics. We soaked savoiardi in espresso and rum. We hung the copper pots back on the wall at odd angles. And always, always, she talked about the war. Vacca miseria.

An enormous, wizened oak tree split the dirt road to her house in California, surrounded on three sides by horse enclosures. The fences were easily climbed regardless of an austere incline. I could scrape over or under her neighbor Arthur’s gate, and then to freedom. No mobile phone tethers then, just cow pastures and a steep climb. Ricardo managed her acreage and lived with his children in the house shaped like a turret down the long drive; Jone prepared his taxes and application papers while they practiced together for the citizenship test. Her own process lasted over 15 years.

Jone collected stories as she collected thimbles and silver spoons, each laid in a black velvet case and tied with a length of green ribbon.

Her home’s expansive lawn was cut away in increments to make space for a large strawberry patch, a vegetable garden, and three thin willows whose roots never fully took. She hung silver ribbons in a field of cherry trees to keep away the birds, while we picked miner’s lettuce along the shallow creek bed. It could be a healing place at times, in so much still air. When we lost our own home after my father’s death, we resettled there with her, in the bottom floor, cut into the hill where we could convalesce or asphyxiate with fewer windows.

Then the Allies arrived in Milano on trucks, bringing chewing gums, chocolate, music, boogie music. But the partisans wanted to punish people who were sympathetic to the Germans. There was a young girl who had a German soldier as a guest. Perhaps he was not a bad German. Maybe he also was a victim of the war. But they shaved her head, walked her weeping in the street with a sign. I felt so guilty, I do not know why.

When she was 14, Jone’s neighbor in Italy hung himself in the courtyard. Another, 19, shot himself. Why? The war was over, but maybe is inside him.

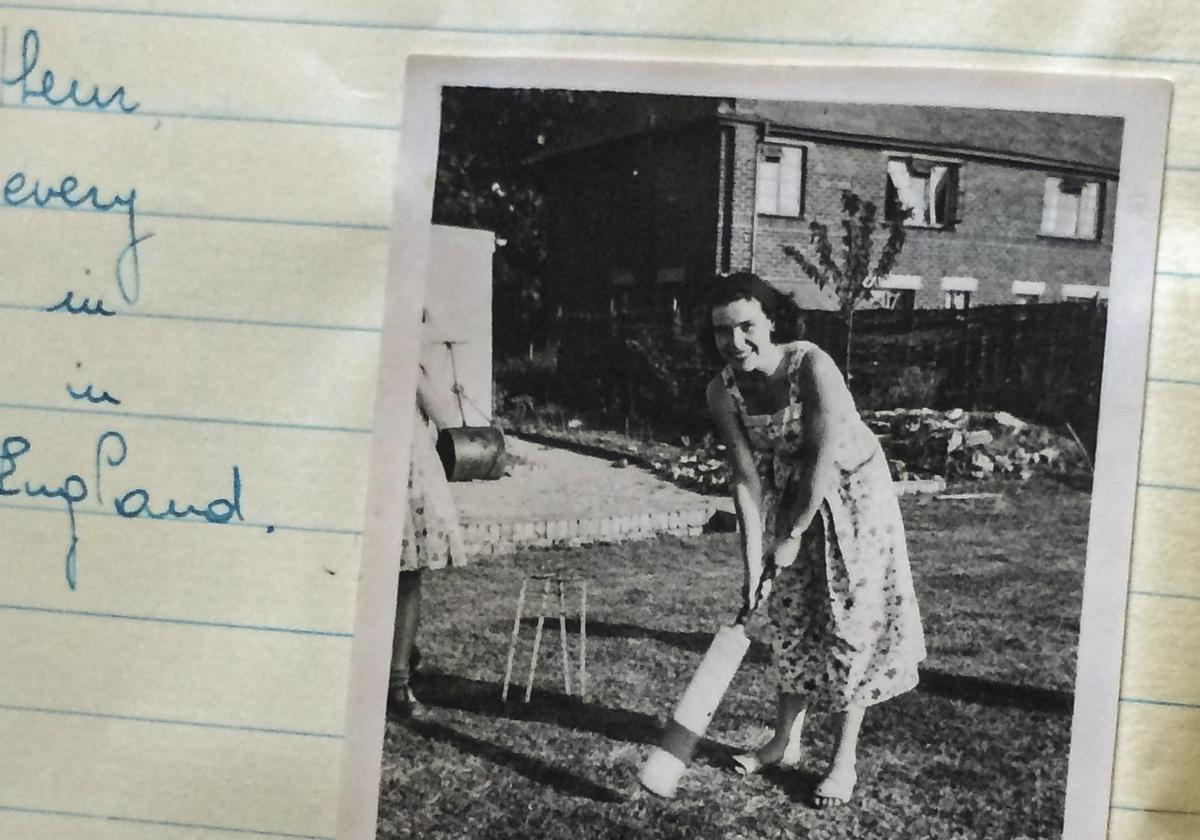

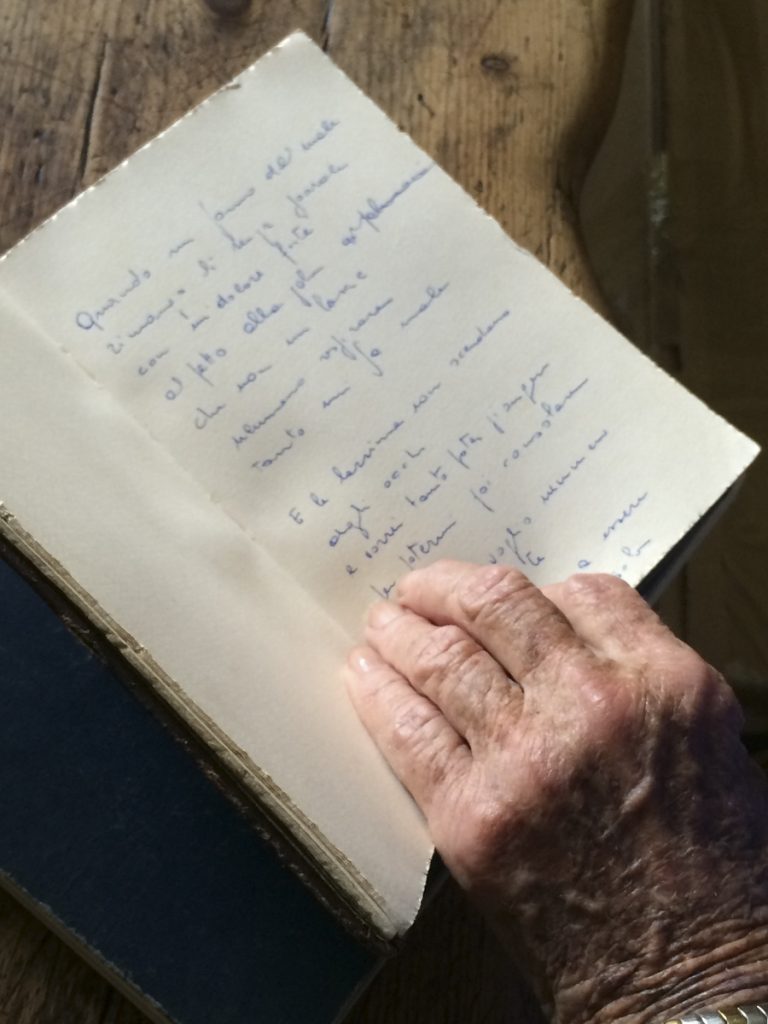

About 85, she began to forget her English. Yesterday, my mother found her hiding under a table. She does not know her name. She does not remember Lomazzo or me or her miserable cows. Tonight I found a photograph of her from maybe 10 years ago. She is clutching a book of notes with tea-stained edges, dated 1951. I asked to borrow it once, then took the photograph now on my screen: a poem notated in solfege. The libretto is smudged in blue ink, the pitches in pencil; there are too many lines I cannot make out.

le Cose Importanti:

Tu non sai quanto sia importante

la prima — — — — — — — — –

il primo — — — — — — — — –

la prima volta

— — — — — — — — — — — —

and so on, for six more lines, mostly smudged. I wonder what was so important.

EJ Bowman was recently named a finalist for both the DiBiase Poetry Prize and the Florida Review Editor’s Choice Award. She is currently enrolled with The Writers Studio at the University of Chicago and the Community Literature Initiative out of the University of Southern California. EJ lives in Laguna, California, with her husband, gecko, and numerous neglected houseplants.