STORY AND PHOTOS BY KAMI L. RICE

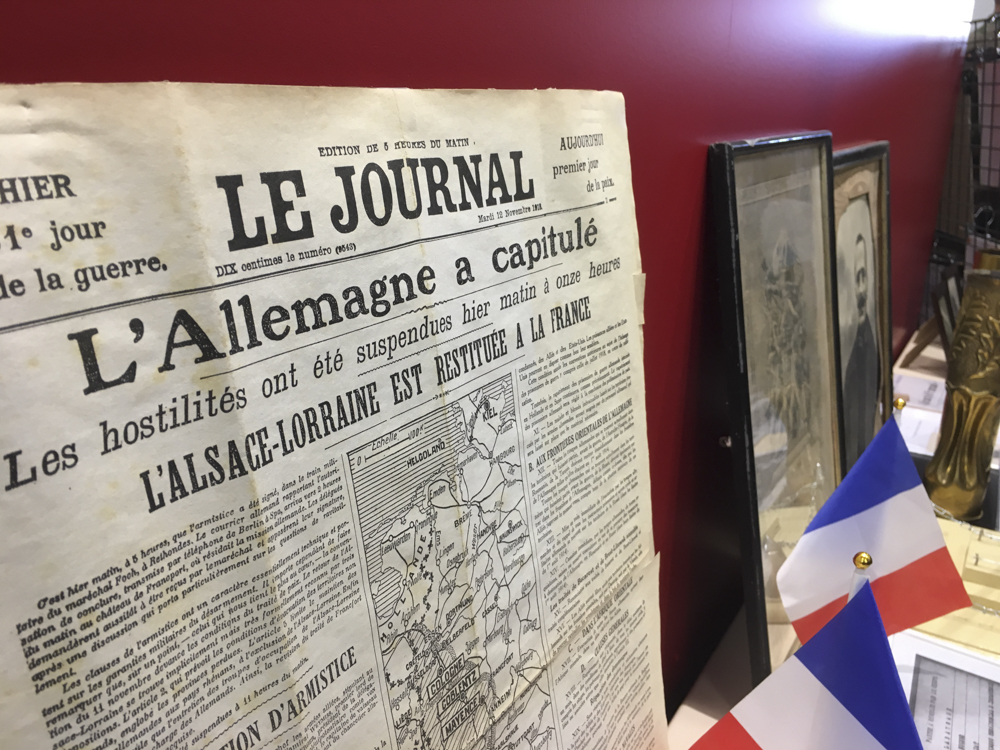

Unlike Paris, the French commune of Jurançon, with its renowned vineyards and 7000-plus habitants, didn’t make international headlines for the commemoration events it hosted last Sunday, November 11.

Along with so many other French communities, Jurançon, in the foothills of the Pyrenees in southwestern France, read aloud the names of its sons who died for France during that first Great War, which officially ended 100 years ago, at 11 a.m. on November 11, 1918. In one of his speeches of the day, Michel Bernos, Jurançon’s mayor, noted that the list of names would be one and a half to two times longer were it to include those whose remains were never found or able to be identified.

Bernos also used his speeches before the local dignitaries, former and current soldiers, citizens, and a small cadre of Americans living locally to call attention to American intervention in that war—at great cost to American lives—and the persistence of Franco-American friendship. One of the Americans read a statement sent for the occasion by Daniel Hall, the American consul in Bordeaux.

The morning began when the multi-generational crowd of roughly 150 people filled Jurançon’s St. Mary’s church for mass before exiting to the World War I memorial outside the church. Here were read the names of Jurançon’s 200 official dead (out of a population of around 4,500 at the time); speeches were given; school children sang part of “La Marseillaise,” the French national anthem; flowers were laid in honor; a junior-high-age trumpeter played solemn notes; and doves were released.

Next it was on to a rugby field to watch the sequenced arrival of four camouflage-clad parachutists, who floated to the ground underneath white parachutes, each with a different flag flowing dramatically behind him. The parachutists hale from the nearby School of Airborne Troops (École des troupes aéroportées), and the rugby field they landed in is named for Georges Guynemer, one of France’s most celebrated WWI fighter pilots.

Finally, with glorious fall sunshine bathing the event in extra cheer, the crowd reconvened at the day’s third site to celebrate Franco-American friendship with the planting of a symbolic pecan tree on the grounds of L’Atelier du Néez, a cultural arts center on the banks of the Néez. This site too is highly symbolic as it was formerly an airplane motor factory that was reportedly taken over by the Germans toward the end of World War II and used to build motors for their own planes. The French Resistance put a stop to this by blowing up the factory.

WHY PECAN TREES?

Though the oral history version of the story has yet to be supported with evidence providing 100 percent certainty of its veracity, researchers have found enough historical clues to strongly support the claim that Thomas Jefferson, man of the land that he was, brought the pecan tree to France during his term here as American ambassador from 1785-1789.

Primary among the evidence is the tree known as “Jefferson’s pecan tree.” The nearly 100-foot tall tree, with a circumference of nearly 15 feet, still towers on the grounds of the Château Carbonnieux, to the south of Bordeaux in western France. Estimated based on its size, its presumed age of more than 200 years corresponds with Jefferson’s known visit to the chateau during his three-month tour of southern France and northern Italy in 1787.

Given this history, the Bordeaux-based organization Les Pacaniers de Jefferson (Jefferson’s Pecan Trees) has set out to plant pecan trees around France as a symbolic witness to the intangible cultural heritage shared by France and the United States through their long friendship. Pecan trees are native to North America and are the state tree of Texas.

As Dan Hall, the American consul, noted in our interview, “France and the United States have never been at war, which is not necessarily true of some of our other very, very close allies. And we have this amazing history together. So it’s a matter of on the one hand ‘Vive la différence,’ and on the other hand we’re going to be going in the same direction. There may be discussions on how we get there or what the priorities ought to be, but fundamentally, we share a love for liberty, and we’ve got this great relationship that goes all the way back to Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson and will extend forward in the future.”

A 2014 article in The Guardian posits more succinctly, “Without the friendship of France there would be no United States as we know it.”

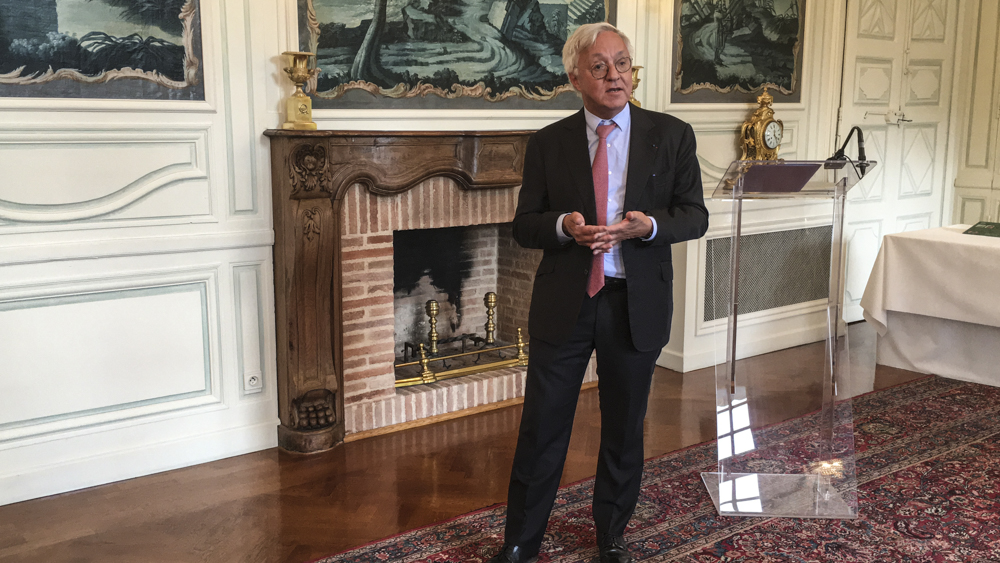

“These plantings should be understood as a gesture of thankfulness to the American people, a symbolic and diplomatic gesture following in the footsteps of the Statue of Liberty, which was given by France to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the American Declaration of Independence and which welcomes immigrants to New York’s port, and also the equestrian statue of Lafayette given [to France] by American school children, as organized by the Daughters of the American Revolution,” explained Bernard Dalisson, president of Les Pacaniers de Jefferson, in a speech delivered in French at planting ceremonies. “These trees, living witnesses of that which the sacrifices of our relatives have brought to us, will be, we hope, just as much a harbinger of hope and peace for future generations.”

American students are likely to know that the Statue of Liberty was a gift from France, but understanding why France would give the United States such a gift requires digging back into the history of relationship that the (much cheaper and smaller) pecan trees attest to. Given that the United States is often better at looking forward than looking back, while France often does better at the job of remembering the past, it’s appropriate then for a French organization to take on this particular task of remembrance and testimony.

AMERICAN REPRESENTATIVES

On a gray October 15, a handful of Americans living in and around Pau, the 75,000-person capital of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department that covers the southwesternmost corner of France, had joined Consul Hall and Les Pacaniers de Jefferson’s Dalisson for three other official pecan tree planting ceremonies.

These same Americans plus a few additions also attended the Jurançon event, yet none of them have formal roles as American representatives. David Blackburn, an American who has lived in Pau for years, is the connector who keeps these local Americans loosely organized and in touch with the consulate in Bordeaux. All of us were representing the United States at these events thanks to nothing more than the passport we carry, our interest in being involved in the community, and Blackburn’s invitation.

The American consulate in Bordeaux is staffed only by Hall and two others, and Hall said they rely significantly on their partners to bring them projects and help them make the connections that serve their tasks of cultural cooperation (including school visits and academic exchanges) and economic and commercial cooperation (in particular, talking with French companies interested in investing in the United States in ways that create jobs and economic growth in the U.S.). Being part of a small team has helped Hall learn viscerally how important partners like Blackburn are.

“Here we are sitting in the magnificent home of an American expatriate who’s lived here for a long time and who has developed amazing relationships with local authorities here, with the whole city really, and if it were not for the fact that he’s been in touch with our office for a number of years, with my predecessors as well, we wouldn’t have the same ability to be present here in Pau and to engage.”

The October events were much smaller affairs than the one this month in Jurançon. The first was presided over by the mayor of Pau, François Bayrou, president of the national Mouvement Democrate political party and former presidential candidate. Next up was a private gathering of the American group with Gilbert Payet, the préfet (appointed administrative leader) of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department. And finally, there was a community event in 13,000-resident Billère, a commune extending along the western edge of Pau.

DIPLOMACY FAR FROM THE WHITE HOUSE AND ÉLYSÉE PALACE

Participating in these formal yet informal ceremonial events that most American and French people will never know are happening, in contrast to the words and tweets exchanged between our presidents, one is struck by the easy down-to-earthness of it all, while also sensing that these exchanges taking place in the shadow of the Pyrénées, and photographed only by the local newspaper, matter.

“In this region in particular I find that there’s a tremendous amount of very deep-seated affection for the United States, and that’s something that the 24-hour news cycle does not capture and that by virtue of being here in the region [instead of being based at the U.S. embassy in Paris], being able to travel out and do the types of events like we’re doing today, we’re able to capitalize on,” noted Consul Hall on that Monday in October.

According to him, “Events like today really help us to put our relationship [the relationship between France and the United States] into the long arc of our historic relationship. It helps to in a way also connect on a personal level with people, also reassure people about the United States, the fact that the fundamental interests of the United States are aligned with those of France and of Europe in general and also the people-to-people ties. There’s a great story to tell here in Pau with the presence of American and British families who were here for years, decades, if not centuries in this region of France, and events like today help us to remind ourselves and everyone else of that fact.”

If the relationship between France and the United States were something that exists only at the presidential level, it wouldn’t be enough, said Jurançon mayor Bernos, speaking to me in French on November 11. “The friendship is strengthened at the level of the youth, the elected officials, the territories, and it’s also strengthened by the fact that it’s always reassessed and reinterpreted. Thus, the local level is even more important than the level of the heads of state, because the heads of state change, but…the democratic values that are represented by your founding fathers and by our constitutional system, this exceeds our heads of state. What’s important is the mayors, the citizens, the athletes, the youth.”

Jean-Yves Lalanne, mayor of Billère, said that the leaders of Billère invited town residents and the local Americans to the pecan tree planting ceremony because in general they want to facilitate friendship between people. And for this event, those people were American and French.

“This event came together a bit by chance, because in Billère there are villas built by English and Americans, a community that has mostly disappeared but that left behind a lot of beautiful homes from the pinnacle of their presence at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. It was an important community,” he explained in French on October 15.

“And today we [also] celebrate 100 years since the end of World War I, so it’s [also] an opportunity to highlight the American Expeditionary Forces’ arrival which helped shorten World War I. Because we want to be welcoming to all communities, this was an opportunity to plant a pecan tree that highlights good relations between France and the United States.… It’s a chance to make some history that can forge stronger bonds between people and communities.”

THE UNPAID AMBASSADORS

Hall said that when he talks with groups of American students studying in France, he tells them that whether they realize it or not, they are actually a kind of ambassador among their host families and various French friends and acquaintances.

“They have a great opportunity to really represent the United States and all that’s best about the United States,” he said he tells them. But then he chuckled as he recounted this and noted that the converse is equally true, as he also tells students: They can unwittingly give people bad impressions of America and its people. The students, and likewise all Americans living abroad, “are thrust into that role whether they realize it or not.”

Madeleine Croteau Duboé, one of the participants at all four pecan tree planting events, counts herself lucky to be a dual American-French citizen. “I don’t feel more of one or the other, as a citizen of the world. I’m always pleased to celebrate my two heritages, [since] my family is of French origin,” she noted, adding that “the pecan tree planting was an opportunity to share with the very small American community here in Pau. These opportunities also comfort me in the fact that Franco-American friendship is still alive and well.”

Around the time of these pecan tree ceremonies, an unimportant seeming task unexpectedly gave voice to the on-the-ground relationships my home country has with the country I live in. I settled down in the salon chair of a new-to-me hairdresser. At first I’d thought he wouldn’t be very chatty, but he turned out to be quite opinionated, with plenty to say as he snipped my hair.

When he learned that I am American, he suddenly spoke as though he were the official porte-parole, the spokesperson, for all French citizens: The French owe a debt of gratitude to the Americans, he said. People from our two countries are forever tied together by the American dead bodies that littered that beach in Normandy during WWII.

They died for us, he said, with a touch of awe in his voice. Then he added passionately (in loose translation of his French), “Without them not only would we be speaking German now, I never would have met my grandfather.” His grandfather had been a prisoner of war. Without American participation in the invasion that changed the course of the war, grandfather wouldn’t have stayed alive.

This coiffeur is just a regular citizen, years removed from those events of WWII, who still feels such a personal affection toward Americans—though he also mimicked some unflattering American qualities while being equally harsh on his own country. (Remember, he was opinionated.)

As he and I agreed, though, every nation has good and bad qualities, just as do the citizens who represent our countries to each other, far away from any headlines.

Kami Rice, Anthrow Circus’s editor, plies her insatiable curiosity from a base in northern France and from perches in coffeehouses, cafés, and friends' homes the world over. As a freelance journalist, she has reported for the Washington Post, The Telegraph, The Tennessean, The Bulwark, and Christianity Today, among many others. Her more creative work has appeared in Another Chicago Magazine, The High Calling,and Washington Institute's Missio.Her French to English translation has been published by Éditions Beaux-Arts de Paris. She also edits manuscripts and articles for a variety of clients and loves learning about the lives of regular, real people wherever she finds herself.