Image provided by the Detroit Institute of Arts

BY MARINA GROSS-HOY

A regular column in which our resident museum educator helps us fall in love with museums and their insides.

The Detroit Institute of Arts is a gem. It has one of the largest art collections in the United States, with objects spanning from ancient Mesopotamia to contemporary America.

The reason for my visit on a blustery March afternoon was to test Lumin, the museum’s brand new augmented reality mobile experience. The DIA is the first art museum in the world to develop such a project. The name is inspired by the Latin word for light (lumen) and evokes the spark that takes place when visitors have an enlightening experience with an artwork.

I decided to prepare for my digital experience with a purely analog one. Inspired by Lumin’s name, I explored the European galleries on the hunt for light and moments of illumination.

What first struck me was the actual lighting. So much thought goes into the light in a museum gallery, from aesthetic choices to preservation requirements (where light is measured in units of lux). But as a visitor, I rarely notice the quality of light unless there is an annoyance, like reflections on an especially shiny painting. But on this visit, I began to appreciate the subtle and intentional uses of light to facilitate observation.

The physical force of light added another layer to the artworks. The gilt copper angels of a reliquary from 1300 gleamed, and the white enameled terra cotta Madonna and Child had a heavenly shine. These religious objects came alive in the light, even when removed from their original contexts of devotion and placed in a decidedly secular institution. I tried to imagine how the reliquary would sparkle in its original fourteenth century light source: candlelight. But even modern light flirts with the materiality of these objects.

The absence of light could be equally powerful. Shadows carved additional levels of detail in statues, making them more dynamic. One sixteenth century terra cotta Italian scholar in particular seemed apt to spring to life and start lecturing as I passed him. The drapery of the carved cloth on a wooden Virgin and Child became monumental, boldly flowing around the towering figure. These masterful artists sculpted shadows to help make their figures more divine or more humane.

Another woman, painted by Bernardino Luini, is painted facing a bright light source. But behind her is an enveloping darkness that is not pierced by the light; this deep shadow becomes a tangible part of the portrait.

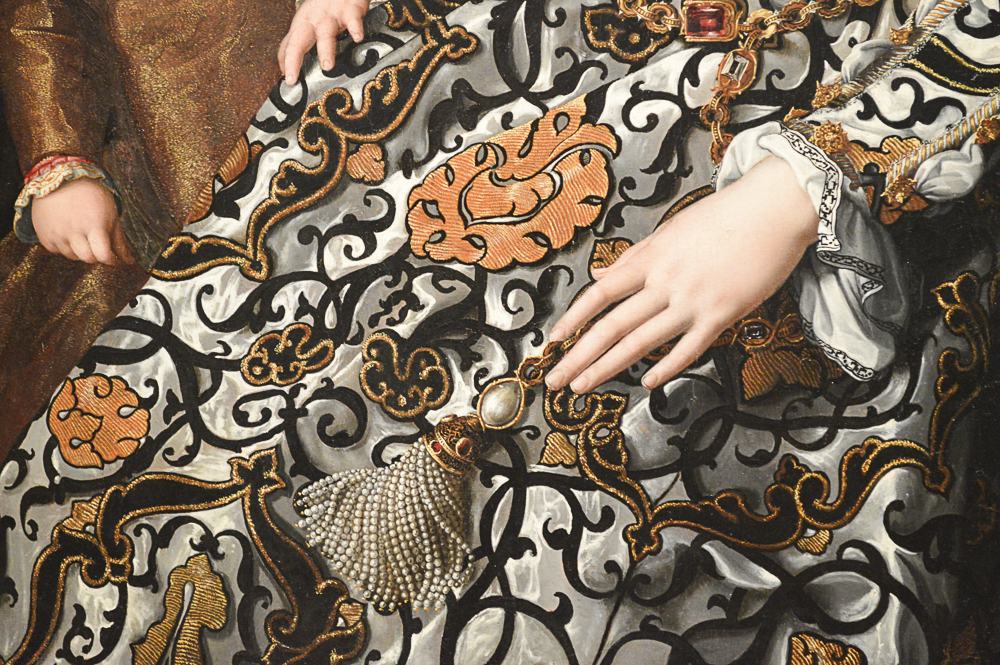

Painters created their own light and shadows within the world of their artworks. I was especially drawn to the depictions of fabric in the dress worn by Eleonora of Toledo. The luscious gown shines in the constructed light, letting us imagine the texture of the luscious textiles.

Two Italian paintings struck me with their representations of light sources. In the first painting, the night sky is filled with tiny holes, as if the end of a thin brush had been repeatedly pressed to the paint. These are actually tiny stars, and each hole was once filled with silver leaf. The artist, Sassetta, was one of the first artists to capture starlight in the 1400s. In another painting, the thin horizon line displays a dramatic dawn. The resurrected Christ, depicted in a glowing gold oval, is the rising sun. This potent imagery links the cycle of day and night to the Christian belief in Jesus’s resurrection.

The most powerful moment of illumination during my visit was my encounter with Fra Angelico’s “Annunciatory Angel.” The artist got his nickname because of his angelic treatment of his subjects. This angel is no exception. He is telling Mary that she will conceive and become the mother of Jesus, with parted lips and gentle gesturing hands. The golds, yellows, and pinks are sublime. The light of the galleries plays with the details in the gold of the angel’s halo, robes, and feathered wings. The angel literally glimmers.

The museum disappeared in that moment, and the only thing that existed for me in the entire world was this calm yet vibrant mélange of textures, color, and light.

You can read about my experience with Lumin over on my website.