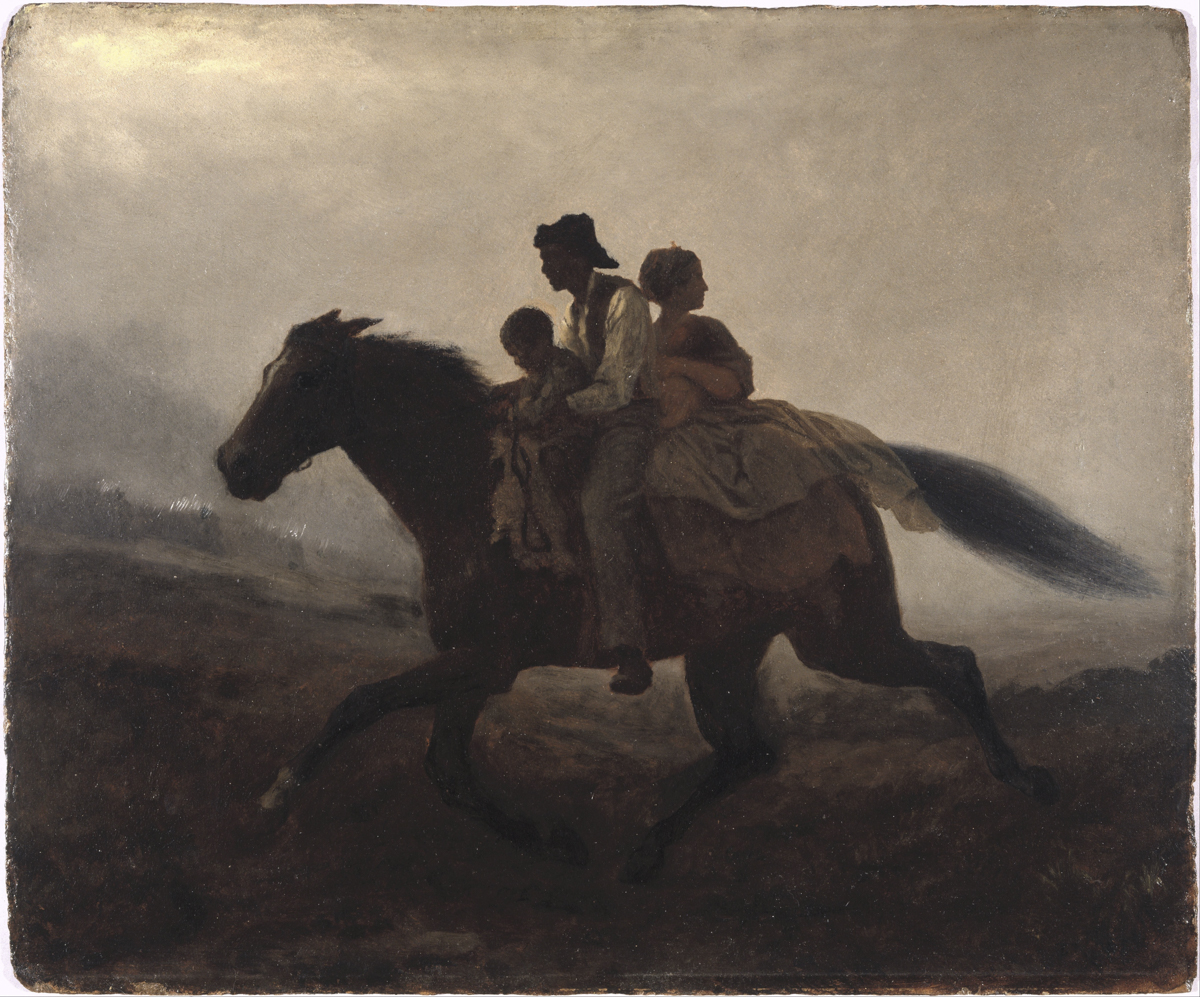

A Ride For Liberty – The Fugitive Slaves by Eastman Johnson. Image provided by Wiki Commons and the Google Art Project.

STORY BY KAMI L. RICE

Take up residence in France and you’ll find that everyday life is infused with history. If you’re a curious person, you can’t help but absorb facts it would take years of history classes and careful concentration to learn back in the United States. Here you see and touch history, observing how its effects are felt even long after its scenes’ original actors have departed.

From dime-a-dozen Roman ruins, to the castle where Henri IV was born, to the ancient port of Marseille, to the angles of Cézanne’s beloved Mont Sainte-Victoire, to the beaches of Normandy, history has come alive during my years of French life.

These history lessons don’t stop with physical sites. For example, reminders of the world’s two Great Wars are ubiquitous, but not only in rebuilt walls and monuments. In addition to memorial services on key dates throughout the year, turn on the TV almost any given night and you will not be hard-pressed to find a series, film, or documentary set during World War I or II.

Despite all this ever-present history, as France’s first pandemic confinement began to ease last summer, I noticed a gap not yet filled in for me: Details of France’s participation in the transatlantic slave trade remained mostly a mystery, though the existence of French-speaking Caribbean islands testify that France did plunge itself into this horrid business. While gaining consciousness of this history hole, I was living only a couple hours south of Bordeaux, a major Atlantic port city on France’s western coast that, I would learn, was the second most important port, after Nantes, in France’s slave trade.

American and British participation in the enslavement of humans is fairly well-documented in films, books, plays, and other cultural and artistic creations in English. But these artistic products don’t tend to regularly implicate France. Thinking this was a function of the language gap and knowing fictional stories in historically accurate settings to be an engaging way to learn history, I assumed I’d easily find French novels that would recount French slave trade history the way English ones do. After unsatisfying online research efforts, I sought in-person help in one of the charming independent bookstores in the southwestern French town I was then living in.

The resulting list of books was very, very short.

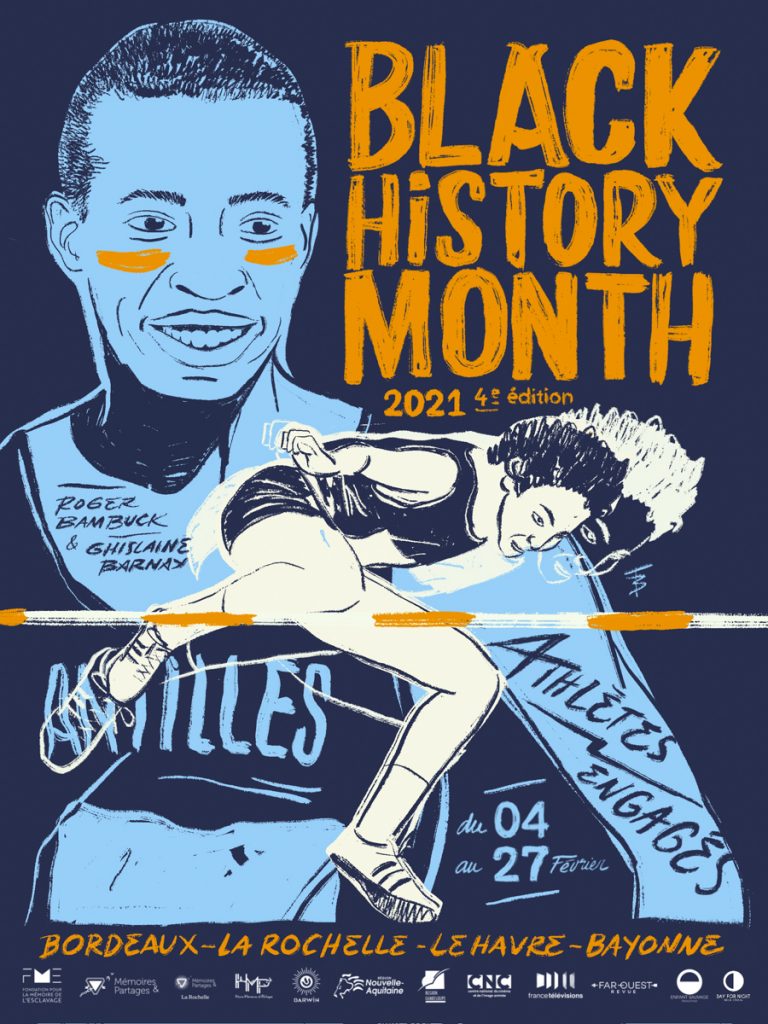

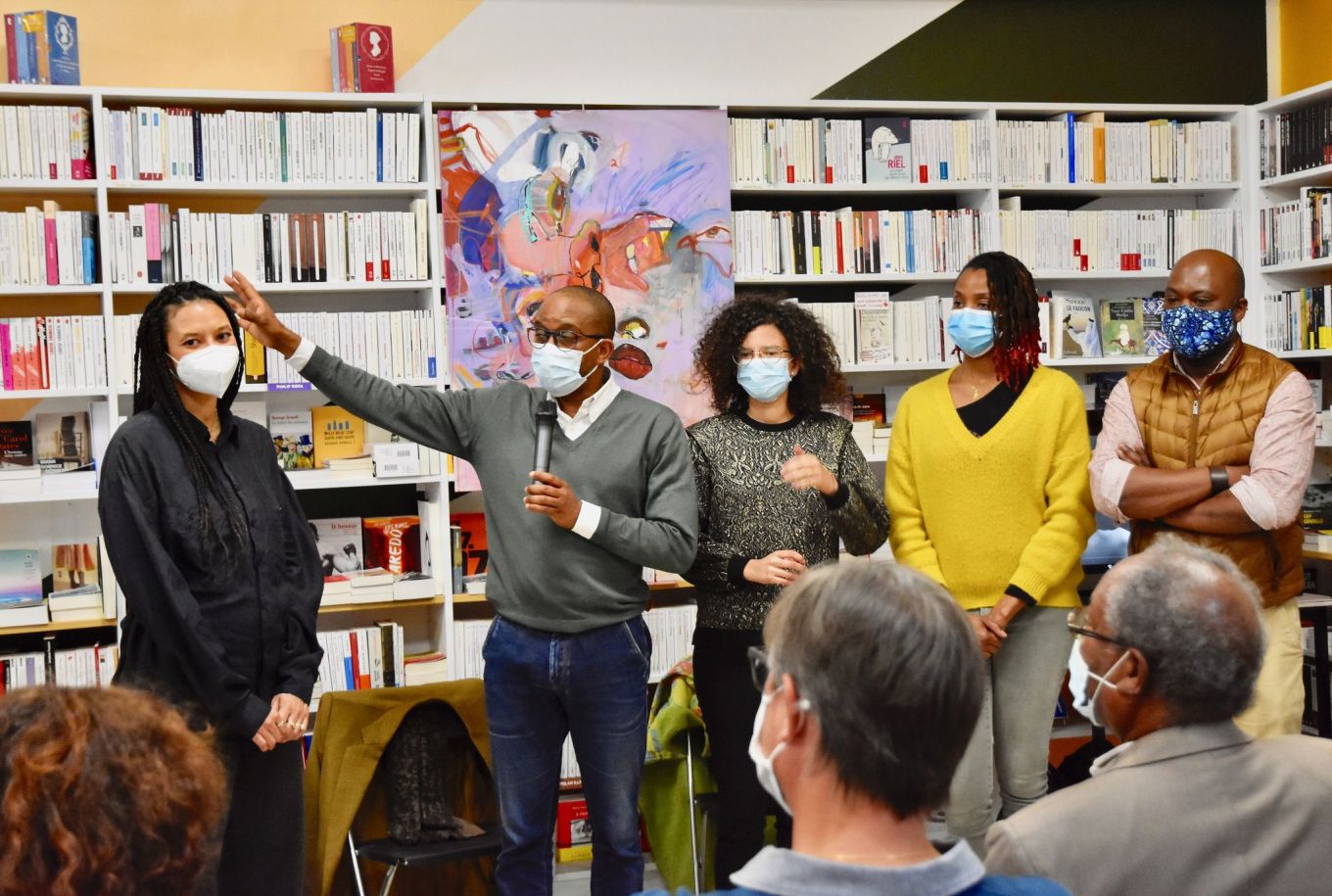

For the fourth year running, the Bordeaux-based organization Mémoires & Partages organized Black History Month activities despite 2021’s ongoing pandemic limitations. Four years ago, they decided to retain the American name for their month of educational and commemorative programming, a show of respect for its American roots. (The event first launched in the U.S. in 1926 as National Negro History Week before evolving in the late 1960s into a full month of focus.)

Karfa Diallo, founder and director of Mémoires & Partages, clarifies that despite the U.S. links, their Black History Month programming focuses specifically on the situation and history of Black people in France as well as “the history of the world because … it’s the same human experience, and we know that to be Black today is to often be confronted by racism and violence. This is the global context of this event.”

Motivated by a posture of vigilance and collective remembrance, Mémoires & Partages has been working in France and West Africa’s Senegal since 1998, raising awareness of France’s participation in slavery and the slave trade. Throughout the year, the organization hosts seminars, works with schools and universities, and organizes guided tours and exhibits.

But through Black History Month, they’ve found increased connection with youth. “Young people, European, French, have a strong American awareness. They’re very influenced by American culture,” Diallo explains. Retaining the American moniker has facilitated connecting with these youth in ways the organization hadn’t managed to do before celebrating Black History Month.

Mémoires & Partages’s events in four Atlantic and English Channel port cities were the only Black History Month activities organized in France this year. Diallo notes, though, that “events related to the murder of George Floyd and Black Lives Matters [in 2020] truly changed people’s awareness. Today there’s a sharper perception of the problem of racism and of structural racism.” If not for the coronavirus crisis, he surmises there would have been other February initiatives addressing how Black history and current conditions influence French society.

The organization’s 2021 events opened on February 4 with a ceremony at Bordeaux’s town hall. The date references February 4, 1794, when, influenced by events in the Haitian Revolution, France was one of the first countries to abolish slavery and the slave trade for nearly all its territories. However, this abolition was revoked in 1802.

Officially, slavery and serfdom had been outlawed in continental France since 1315 as decreed by King Louis X. The official position was that any slave touching French soil was freed. But this official policy wasn’t applied to France’s territories and colonies and wasn’t enforced in mainland France in the slave trade era. Though some slaves were on French soil because, for example, their masters passed them off as domestic servants, large-scale slavery took place on islands and territories far from the daily lives of most French citizens. It wasn’t until April 1848 that France definitively abolished slavery and emancipated all slaves.

See Anthrow Circus’s 2020 coverage of protests against police violence in France and two other countries.

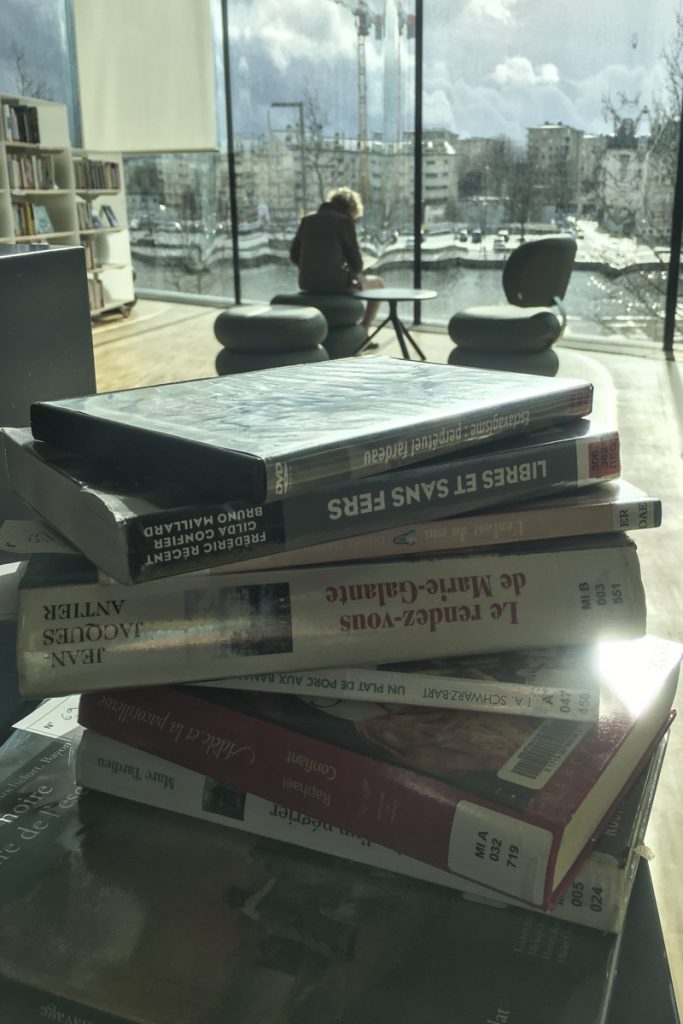

March sun and windy rainclouds fought an epic battle as I blew into the library in my new Normandy town armed with my research project. The first librarian I approached handed me off to a slightly older one covering the desk in the history and biography section. Both seemed intrigued by my question about slavery in French fiction, in part because neither of them could answer it easily without digging deep into search engines.

Over the course of an hour, through our masks and pandemic-era plexiglass, the librarian and I chatted at her desk with shared curiosity as she worked through her library’s catalogue, the catalogue of the French national library in Paris, and the search-friendly listings on Babelio, the French equivalent to Goodreads. I was still on a quest for French novels that treated or were set in the context of the transatlantic slave trade. I wanted to know if a librarian in a sizeable northern town’s large, modern library could supply me with a longer list than the small bookseller down south.

One combination of search terms on Babelio was particularly telling, producing only nine relevant books of fiction by French authors compared to 166 by American authors translated to French. As the librarian exclaimed, “Ça parle!” (“That says something!”)

When we broadened the search beyond fiction, we found many more books in French documenting France’s history with slavery. “The subject is treated,” the librarian summarized. “It’s not ignored. But it’s treated more in works of historical nonfiction.” She added, though, that “it is not a historical subject addressed as much [in daily French life] as others.”

When I finally exited the library into the wind that had defeated the sun’s efforts, I was loaded down with a much healthier stack of books than I’d procured from the bookstore months earlier: two chapter books for younger readers, a few novels, and a couple nonfiction books. And I’d left others behind for another time. For the motivated, some books on this topic do exist, but still, the options were far scantier than the lengthy lists offered by two libraries and a used bookshop consulted back in the U.S. for comparison’s sake.

Both Patrick Serres, president of Mémoires & Partages, and Diallo, the director/cofounder, say the situation in France is “très contrastée,” meaning there are contradictory realities around the country’s reckoning with its slaveholding past.

For example, they acknowledge a significant institutional effort in France since 2006. In May 2001, the French parliament adopted “Taubira’s Law” and became the first country to recognize slavery itself as well as the transatlantic and Indian Ocean slave trades as crimes against humanity. In 2006, the French government established May 10 as a national day of remembering the slave trade, slavery, and their abolition. As a result, this history is included in the national curriculum for middle school students, and each May 10 the French president gives homage at a symbolic location with the mayor of that town.

While this day of acknowledgement has the same official weight as May 8 and November 11, days commemorating the losses of the World Wars, Serres says it’s unimaginable that even the smallest French municipality would not hold a solemn ceremony on those two days.

“The least mayor who doesn’t have a ceremony to honor the dead, he’d be politically dead the next day … which we would understand,” Serres says. However, “for May 10, we have multitudes of municipalities, basically the totality of French towns, who do absolutely nothing to commemorate,” not even an artistic or cultural event to remember the history of slavery and those who suffered.

In reference to my search for relevant literature, Diallo says there are very few, practically zero, novels about this slave history, though he affirms the Normandy librarian’s findings that there are French works of history for specialist audiences.

He posits that one reason more American literature and film address and acknowledge slavery is that there has been a sizeable and influential Black American middle class with the means to invest in “the imagination.” He adds, “In the United States, there is an intellectual, cultural, and artistic creativity. There are important films that recount these stories; there are important works and important books that are known today all over the world. In France, we don’t have that.”

Sébastien Sacré, an associate professor teaching in the University of Toronto’s French department, grew up and did his undergraduate studies in France before relocating to Canada. He says many French Caribbean authors have written about slavery, the consequences of slavery on descendants of slaves, or various minorities on the Caribbean islands post-slavery. But while these books are easy to access in most French bookstores and are awarded prestigious literary prizes, he never learned of them during his schooling in France.

Rather, it was a French Caribbean literature class during his master’s degree studies in Canada that introduced him to these authors. A course he’d taken the previous year in France on francophone literature focused only on authors from Quebec and French-speaking Africa. Sacré says that seven to 10 years ago, when he was still visiting France regularly, novels by French Caribbean authors were usually classed in the “foreign” category in bookstores.

“It is clear that the experience with slavery did not affect literature like World War I and World War II did,” Sacré says. “Of course, I am not sure why, but it seems that World War I and World War II sell well, as the majority of the French population was affected by them and most people have stories within their families.” It’s not only written works that are affected by this gap. “I am not really aware of movies dealing with slavery the way we have such movies in North America,” he adds.

Considering that, officially, slavery didn’t exist on metropolitan French soil, it begins to make sense that fictional works set in France during the slave trade era don’t have to mention slavery to be historically accurate. Whereas for works set in the French Caribbean or in the Americas where enslaved people were tilling the soil, any historically accurate fictional work has to acknowledge slavery’s existence.

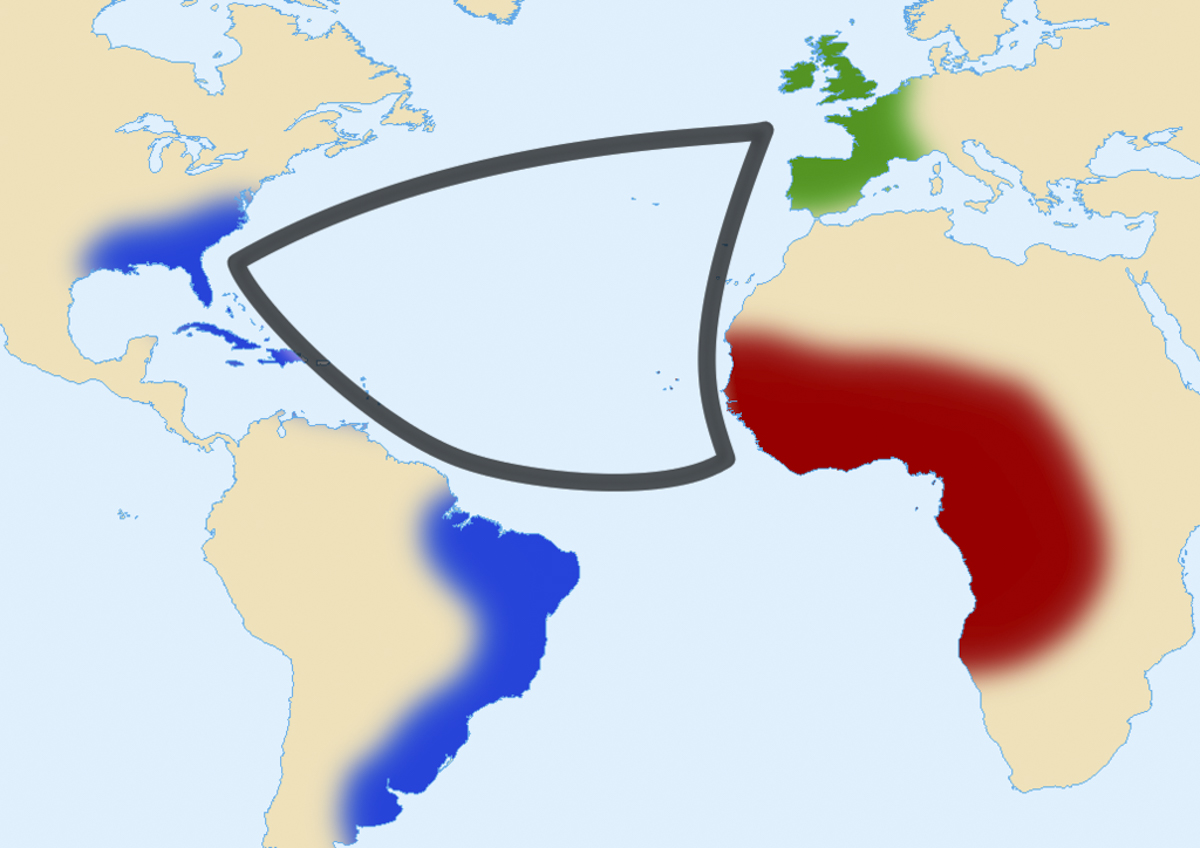

The Triangular Slave Trade Route, map provided by Wiki Commons.

In another “très contrasté” twist in this story, France has been a traditional haven for Black American creatives escaping slavery-era America and the racial tensions that have lived on since then. Author James Baldwin, performer Josephine Baker, painter Beauford Delaney, playwright Victor Séjour, and, more recently, musician and actor Lenny Kravitz are a few of the celebrated African American artists drawn to France.

Famously considering itself “colorblind,” France doesn’t gather race and ethnicity statistics during censuses or other data collections. But Myth of a Colorblind France, a documentary released last year by American Alan Govenar, is among the voices questioning whether colorblindness truly defines French culture, despite the freedom African American artists have found here.

In a France-Amérique interview about the film, Govenar acknowledges that there has historically been a double standard, one that persists today, of better treatment of Black Americans than of French citizens from Africa. “African Americans who came to France are treated differently than people of African descent. France was a slaving nation, but slaves were never brought to French soil, and this legacy, combined with decolonization and the influx of Africans into France after the Algerian War, has had a profound impact.”

“French society has remained highly stratified when it comes to race and culture,” he continues. “In the film, Tyler Stovall [author of Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light] tells the story of when he came to France for the first time and was stopped and frisked by the police. Once he showed them his American passport, they left him alone. It made him aware of his different status.”

Diallo says that in the 22 years Mémoires & Partages has been at work in Bordeaux, not a single novel has been published from the city relating its slave trade history, a topic he says remains a taboo in the region, especially in the artistic milieu. However, he’s encouraged by the evolution he’s seen. Things are moving, he says, and he anticipates that in coming years, there will be artists and creators taking up the subject, especially as they feel liberated by a society that is gradually finding this part of its history less taboo.

He thinks the arrival of people in Bordeaux who are from Paris, the United States, and other places and who are thus more comfortable wrestling with this past will help the Bordelais grapple with a history that implicates their own families. Already for Black History Month and other events, Mémoires & Partages is finding an increasingly enthusiastic and supportive audience.

And in February, Anne-Marie Garat, a prolific novelist living in Paris but born and raised in Bordeaux, released Humeur Noire, a literary work of nonfiction that delves into her hometown’s challenges of dealing with its slave history. The book’s catalyst is what Garat views as problematic word choices observed in the exhibit on slave trade at Bordeaux’s Musée d’Aquitaine.

Attentive to words’ precision, Garat said in a Prologue interview that she sees “slavery” as a plural word, which acknowledges that slavery is still practiced in parts of today’s world.

“This contemporary slavery proceeds from the same primitive mechanism of enslaving human beings, of reducing them to the rank of productive energy, in the name of profit and political domination,” she said. “Knowing the history of the ‘slaveries’ since Roman antiquity, or even since Neanderthal times, allows us to understand the modern forms of slavery that are … based on the monopolization of human and natural resources by one group exploiting the others. Affirming ‘slavery’ as a plural updates and perpetuates research and reflection on this crucial question for our world today.”

Kami Rice, Anthrow Circus’s editor, plies her insatiable curiosity from a base in northern France and from perches in coffeehouses, cafés, and friends' homes the world over. As a freelance journalist, she has reported for the Washington Post, The Telegraph, The Tennessean, The Bulwark, and Christianity Today, among many others. Her more creative work has appeared in Another Chicago Magazine, The High Calling,and Washington Institute's Missio.Her French to English translation has been published by Éditions Beaux-Arts de Paris. She also edits manuscripts and articles for a variety of clients and loves learning about the lives of regular, real people wherever she finds herself.