TEXT AND PHOTOS BY MIKE PLUNKETT

I can’t tell you how many times Megan and I have nearly tripped over a tombstone during this pandemic.

As our corgi Bentley barks to get off-leash and run through the historic Union Cemetery, it’s easy to nearly twist an ankle on a broken headstone that I could have sworn wasn’t there, even though I’ve walked this spot what seems like hundreds of times.

The cemetery, established in 1857, is the resting place of some of Kansas City’s leading families and a slew of soldiers and settlers from the founding of what is now Kansas City, Missouri. Our Union Hill neighborhood is named after the cemetery, and the cemetery is the unofficial meeting ground for all the local dogs. Bentley has more friends than we do, and like children and the parents they bring with them, his dog friends’ “parents” have become our friends.

Before COVID-19, I hated cemeteries, especially the ones that are unkept. Not just because of the ghosts that walk at night (I’ve seen Coco enough to believe it) but … it’s a cemetery. Walking my dog there was a chore, and this place was a constant reminder of what I thought about this city: old and needs maintained. And not for us.

When I was sent home to work, it was under the guise of a sprint: You’ll be working at home for just a month. There’s paid administrative leave if you need it. Megan, on the other hand, was deemed an essential worker and still left home for work, hand sanitizer at the ready.

At first, the change was great. I’ve always wanted to work from home.

Quickly though, it became clear I wasn’t working from home. I was at home, in a quarantine, trying to make it work.

But this will be quick.

The cemetery is one large loop, with old wagon trails that bisect the middle of the cemetery. Depending on the weather and the time, Bentley and I do the large loop and stop for water at the Sexton’s Cottage, where the visitor center is, or do the mini-loop and hurry home. It also depends on who’s there. Sometimes it’s Blu, Rusty, and Margo. Or Hattie and Fletcher, who live nearby. Bentley’s bestie is Frye, another tricolor corgi who lives three doors from us and often comes along. When Megan takes him out in the afternoon, they meet up with Casey Jones, Bentley’s other best friend.

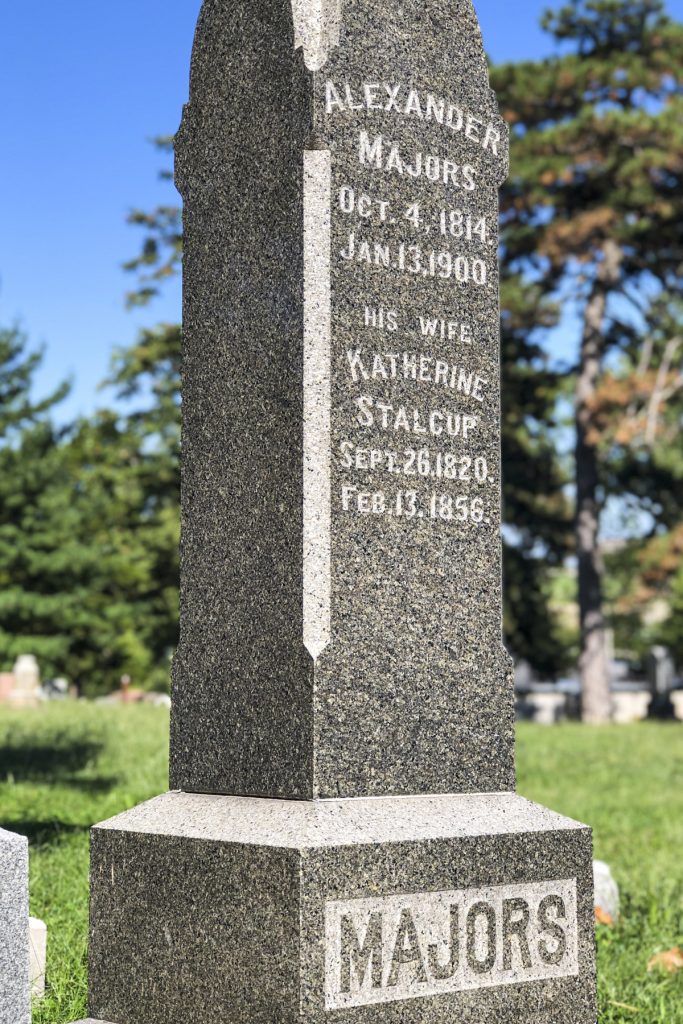

The Friends of the Cemetery created a walking tour. It features the famous souls buried here. Alexander Majors, the founder of the Pony Express, is stop #10. The Pony went from St. Joseph’s, about an hour north of Kansas City, to San Francisco.

James Calhoun, #8, was New Mexico’s first territorial governor. He died on the Santa Fe Trail in 1852. Thomas Jefferson Goforth’s tombstone is on display at #32. He was the first mayor of Westport, now a K.C. neighborhood. He was laid to rest in 1882.

Scores of Union soldiers rest throughout the cemetery. Many come from the Battle of Westport, the “Gettysburg of the West,” where the Union fought back Sterling Price’s attempts to reclaim this area for the Confederacy.

The rest are families. Father, Mother, Infant. Emily, the wife of Reynolds. After 150 years, that’s who they are to folks like me trying to get his dog to go potty. Father. Mother. Historical.

“I am not my thoughts. I am not my emotions.” On a Sunday morning, I was doing a neuro-meditation session. I was working on a content marketing project for a startup. This was research. (Yeah, research.)

It was about two months into the lockdown, and I was screaming for a quiet mind. It was getting louder by the day.

After the research session, Bentley and I went to the cemetery. The large oak trees that shade the cemetery provide enough space to see what is in between the leaves. At first glance, there’s nothing. Space and air.

But I looked closer and focused.

Wait, there is something there. Space holding space.

[Pause. Brief but poignant.]

I’m pretty good at knowing what to do. Even better with direction. Leaving D.C. for Medellín was a knowing. Leaving Medellin for Kansas City was a knowing.

Then, the knowing stopped. Instead, I had thoughts. And emotions. But they weren’t actually accomplishing anything. Just circling. Coronavirus made this more acute.

What can I focus on besides COVID-19, a racing mind, and the dead?

Maybe this: I am not my thoughts. I am not my emotions.

I’ve been seeing a therapist since moving here. I wish I had done it sooner. When the coronavirus went from a sprint to a marathon, I was grateful for the standing appointment.

During one session, we were talking about negative space, the areas in your life that are only revealed if you look at them in a new way.

For those buried in our cemetery for 100, 150 years, they are now old bones below well-trodden ground. But they are there. They are … present? I saw several tombstones of those who lived during the Spanish Flu. What would they say about all this?

Somehow, considering this brought calm. And for a moment, a quiet mind.

The trips to the cemetery became a daily occurrence. Exploring a different part of the plot of land, investigating who else was there. Before the pandemic, I’d heard that folks enjoyed walking through cemeteries. It was calm and peaceful. And so, I learned, it was.

Then Bentley scuffled with another dog. It seems our beloved Corgi and a male puppy didn’t take too kindly to each other. I was at home working when Megan returned, distraught about what Bentley had done.

For his part, Bentley didn’t seem to mind. But for us, that meant a dog quarantine. No cemetery.

We limited his interactions with other dogs, called dog trainers and a behaviorist. He may just be acting out, said one. How old is he? He just turned one. Oh yeah, that’s when dogs start to show their personality and assert what they want and don’t want.

Why our dog had to assert himself in the middle of a pandemic is beyond us. Except we’re sure he’s feeling the stress and anxiety of the world too.

But damn, yet another thing to focus on. Testing, masks, social distancing, lockdowns, now isolation for dog and human. And more so, the ravages of the past, the inability to learn from our mistakes.

The Confederate Obelisk is #15 on the walking tour. It’s mandated by Congress that unnamed Confederate soldiers who were captured and held as prisoners of war be recognized within certain historical cemeteries.

Kansas City and its Missouri state have a tortured history with race. The Missouri Compromise brought the state into the Union as a slave state, and Kansas City still struggles with the decades-long effects of segregation.

The cemetery is blocks away from Troost Avenue, the unofficial dividing line between Whites and Blacks in the city. When the protests over George Floyd’s murder began here, the main point of congregation was at the J.C. Nichols Memorial Fountain near Country Club Plaza. Nichols was a local developer who has been called the father of redlining, the former practice by banks of rejecting home loans in certain neighborhoods to creditworthy borrowers for no reason other than their race.

Where we live, we’re about three miles from the Plaza and could hear the ambulance sirens as they took those injured to Truman Medical Center down the street. By the time the initial protests were done, the K.C. Parks and Recreation Board had voted to rename the Nichols Fountain and the connecting street bearing Nichols’ name. This is a big deal—many citizens had either opposed the name change in the past or didn’t think a change was warranted. Yet, despite this renaming, scores of auditoriums and businesses here still bear the Nichols name.

No one touched the Obelisk in the cemetery. No graffiti, no Black Lives Matter. Like many things in history, it may take more time.

I turned 40 in August. COVID-19 cases are still high in the Midwest. The city extended the mask mandate until mid-January, and sadly, more businesses will close.

We got back from a trip back East, and as I was walking through the cemetery after our return, it took a moment to set in that I was walking through it because I enjoyed the place.

“Boogie Wonderland” came on my iPhone. I did the twist along the road. I hope it isn’t seen as disrespectful.

My mind is clearer, and the anxiety has dissipated. We don’t know what’s next. Like everyone, we wait for the break in the clouds.

When we walk through the broken headstones, we feel another kind of knowing from those souls in this plot of land.

Life will go on.

After returning stateside following their "grown-up study abroad" in Medellín, Colombia, in 2018, Mike Plunkett and his wife Megan Finck made their way to the Midwest. Like Medellín, they found great coffee and craft beer in Kansas City, Missouri. Unlike Medellín, they haven’t found any mountains or arepas con queso in Kansas or Missouri. Mike is a communications professional who worked in a previous life as a journalist at The Washington Post and other newspapers. His work has been syndicated in more than 100 newspapers and media outlets throughout the world, including the Houston Chronicle, Chicago Tribune, and the Sydney Morning Herald. By day, he's a senior editor, working in higher education. By night, he's a story and communications herder, helping mission-driven organizations get their stories and messaging moving in the right direction through Good Boy Bentley (G.B.B.) Creative. He vows to finally finish that screenplay he started in Colombia.