Photo by Kami L. Rice and edited by JC Johnson.

ARTICLE BY SOPHIA RILEY

There were three things I was determined to do during my 14 weeks abroad, only one of which I actually achieved.

The first was to journal every single day, and I did. I scribbled down every trivial memory, everything that made me mad, everything I ate, and then I taped down every ticket, leaf, and pamphlet to boot. Goal achieved.

My second goal was to learn as much French as possible. Alas, even after an intensive language course with a woman named Flo, I found myself stumbling into English at every turn. The Parisians would take one whiff of my pathetic accent and click over to English like it was as easy as changing a TV channel. I guess it is, for people outside the suburban American dream.

My third goal—this one I kept out of even my journal—was to fall in love. I mean, I was in Paris to study art, but if I met the glorious, bilingual man of my dreams during my travels, so be it. I didn’t want it to be like a kitschy romance novel. I wanted to meet a 20-something in the grimy depths of the metro. Perhaps a fellow artist wandering the contemporary hellscape of the Pompidou Centre. Or maybe just some dude smoking cigarettes in Parc des Buttes-Chaumont.

In my mind, it would happen this way: I would become so attuned to the city that I would blend in seamlessly. A pretty boy would make eyes at me—as they do—and when I returned the favor, he’d tell me in French that he loved my red hair. Then, in my own perfect French, I’d reply, “Oh, merci!” Then I’d tell him I’m actually American, and he’d be intrigued. We’d chat, and he’d offer to take me on a personal motorcycle tour, helmet included. I’d wrap my arms around his waist and tumble deeper and deeper in love, not only with him, but also with the City of Lights.

There was this park near my dorm, situated in one of the nicest neighborhoods in the city. Just a little corner place with a playground, a carousel, and a charming grove of trees. After passing it every day on my way to the language academy, I finally decided to walk through rather than around it. This park became my favorite spot to study, sit, breathe. It felt like the kind of place where something lovely would happen, were I patient enough to watch for it.

My chance for romance did come, believe it or not. It was the first week in October, still early in the semester. After meeting up with a close friend of mine in northern Italy, we parted ways in Venice, where I boarded the plane back to Paris alone. It was there, just as I landed, that I met a man named Ben. A French man.

A Man Smoking A Pipe by John Phillip.

Provided by Wiki Commons and the Aberdeen Art Gallery.

We chatted on our way off the plane, and although he was a stranger, I allowed myself to enjoy his company. He helped me renew my metro pass in the airport, and we discovered we were taking the same train line home. We talked for the duration of the 40-minute ride; I learned he was nine years my senior, and apart from his fancy day job, he was a musician. He was impressed by whatever pathetic French I spewed his way, and he liked hearing about my art and my aspirations of being a writer. As his stop approached, we traded Instagram handles. He later messaged me to say he hoped I got home safely, and that was that. I resigned myself to the certainty that I would never see this man again.

But I did.

Roughly a week after my excursion to Italy, my friends dragged me to a bar across Paris. Not being much of a drinker, I guarded our table in the basement while the others bought their alcohol upstairs. I glanced around, absorbing the white noise of French voices until a tall, skinny man with glasses brushed past and caught my eye. It was him, carrying a guitar case over one shoulder and a motorcycle helmet under his arm. My friends returned to the basement to find me chatting with a man they’d seen before; Ben often played at this bar on weekends. It was serendipity.

That night, as I watched him sing romantic songs onstage, my friends kept nudging me in the ribs. “He’s looking right at you,” they whispered. I snorted and shook my head.

It felt like a movie, some kind of manufactured destiny raining down in rose petals. It was the corny Paris magic that, as much as I hated to admit it, I’d been craving. So, when Ben returned to the table and asked me to stay to watch his second set later in the night, I said the only thing that made any sense in that dazzling, dinky little bar.

“Maybe.”

But his second set began just as my friends were climbing the basement stairs to leave, and I followed them. Ben’s voice faded out behind me, and I knew that the moment of magic had ended. Somehow, if I’d really wanted to, I could’ve taken that spark and coaxed it into a flame, but I chose to let it sputter out. It wasn’t even him that I wanted, but the idea of it all. The opportunity for love—or at least a ride on a motorcycle—came and went as fast as rickety train cars flying by underground platforms.

The thing is, Paris is not for lovers. Yes, Paris is the epitome of romance, but when you’re really there, breathing in the smoke and the piss and the overall stench of city life, life in Paris doesn’t swirl like stirred-up leaves. You aren’t the epicenter of a romance novel, but a tiny bug smushed on the edge of a page. Life doesn’t stop for you.

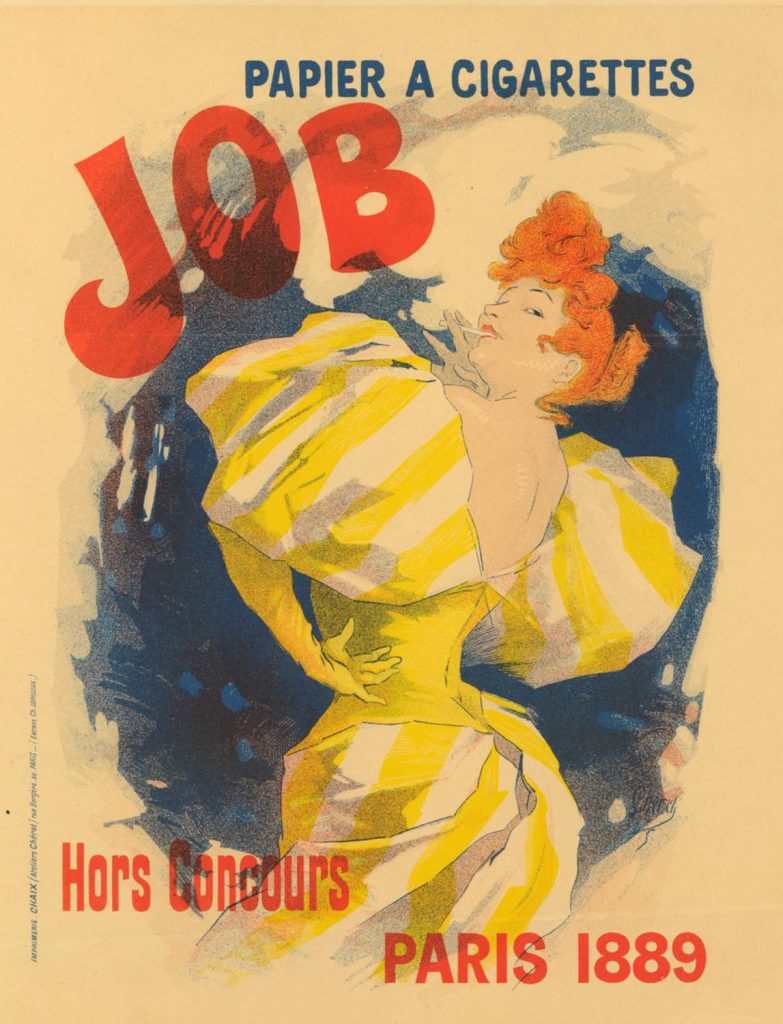

Paris; red-headed woman in striped yellow dress smoking; published as plate 1 in the series “Les Maîtres de l’Affiche,” 1889.

Print made by Jules Chéret. Image provided by Wiki Commons and the British Museum.

As I sat in my park each day and watched the pigeons peck at the cigarette butts in the grass, I kept hoping something monumental would happen. But, in reality, I had come all the way to Paris only to live the same way I’d been living at home. I staggered down the street with my groceries because the French hate plastic bags. I drenched my hands in sanitizer after holding grimy handles on the train. And while I spent entire afternoons lying in my dorm bed watching TV, the city and all its enticing promise passed below my wide-open window, unseen.

The weeks flew. I grew to find comfort in the smell of cigarettes and the rumble of the metro. I traveled here and there, never for long, and never with much money. Nothing was ever perfect. In Venice, I fought with my best friend. In Rome, I threw up on a train at 4 a.m. In Chartres, my homesickness reached me even at the top of a cathedral tower. In Barcelona, I was kissed sloppily and unprovoked, not by a handsome Spaniard, but by that imperfection I’d claimed to have overcome. There, on my 20th birthday, my phone, passport, wallet, and the remainder of my money were stolen.

I found myself completely alone with only my metro pass to guide me home.

I was shaken to my core, not because my European dreams were crushed in the hands of thieves, but because this was just another reminder that the magic wasn’t real. When I finally reached line 10—the metro line that crossed through my neighborhood and the one I now knew like the back of my hand—I broke down in tears.

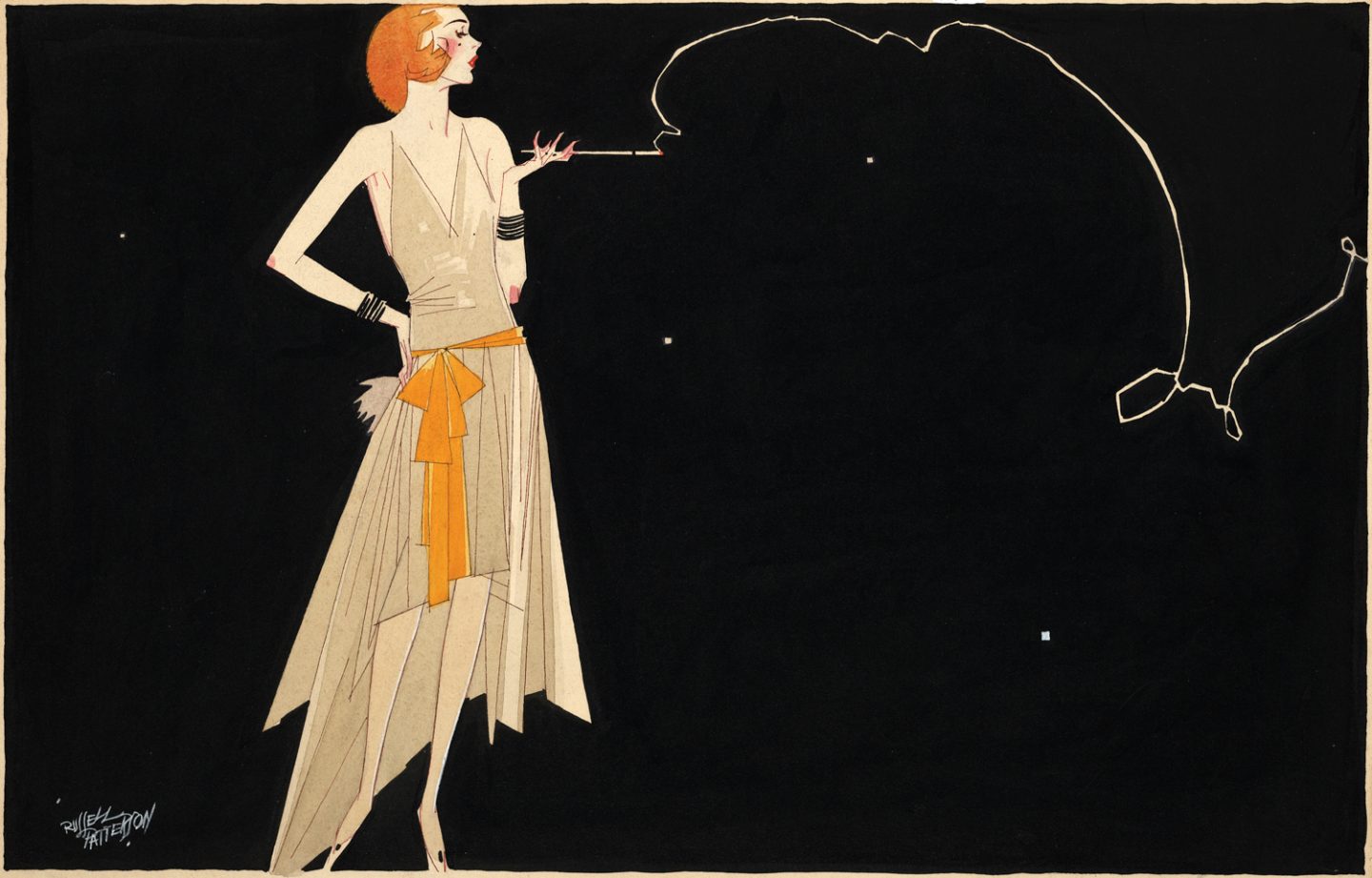

“Where There’s Smoke There’s Fire” by Russell Patterson (1893-1977).

Image provided by the United States Library of Congress‘s Prints and Photographs division and Wiki Commons.

I spent the rest of the semester phoneless, living off 70 euros my friend offered me from the ATM. By the time I packed my bags, I had only a handful of coins left. The evening before I left Paris, I gave the last of those coins to the Roma woman who often sat outside our dorm and I went to the little park on the corner one last time. It was rainy and the park was empty. The vacant carousel spun, glowing a somber yellow through the mist. This place—with its gray skies and strange smells—had become a part of me, and I felt stupid for it.

The next day, my flight home was canceled. Not delayed, but completely canceled. I stood in line for hours, when, finally, late in the night, they announced they’d be getting us a new plane in the morning. I felt like collapsing into a ball and rolling away, shutting the pages of this stupid, wannabe romance novel and tossing it into the fire.

I was quickly “adopted” by an older American couple who had been scheduled for that same flight. They were sensible and chatty, avid wine tasters, seasoned travelers. They saw a vulnerable, tired girl in the same shoes as themselves and put an arm around her, along with a handful of other young, disgruntled travelers—including a Russian man and a French girl I’d befriended. Together, we were put up in a hotel near the airport, where we ate a fancy fish dinner and listened to the planes roar overhead. I told them about the robbery over a bottle of wine, and for the first time, I found it a little funny.

As I curled up in my plush hotel bed, I found myself unexpectedly thankful. I’d never have imagined myself in a situation like this: disheveled, exhausted, and broke, without even a way to call my mother when I landed. But I’d had the chance to experience something unexpected, and yet so rawly human—a chance to connect with people I’d never have met if things had all gone according to plan. I always knew Paris wouldn’t really be a romance novel, but I’d expected to fall in love with something. I just didn’t think it would be the imperfection that I’d fall for. The ordinary chaos tucked into each day, on every continent. The way a park can just be a park and still mean something.

As we boarded the plane in the morning, my ragtag airport friends and I felt like we’d been through hell and back, but at least we’d done it together. They wished me luck getting home, and we parted ways cordially, eager to move along with our separate lives. Before we took off, I dug in my bag. My fingers closed around one last euro, a remainder I’d somehow missed. I zipped it away and stifled a laugh.

Sophia and her family reminisce on their travels at the outskirts of Mont-Saint-Michel. Photographed by Savannah Gutherie.