STORY AND PHOTOS BY ARMON A. MEANS

I cautiously refer to myself as a biker. When possible, I participate in long-distance motorcycle trips, either alone or as part of small groups. This has taken me throughout most of the United States (44 of the 50 states) and parts of Canada via motorcycle.

The majority of this travel happens during the summer months when I have time to be outside the studio and the photography classrooms I teach in, and I often use this travel as a method for producing new artwork.

The first annual Black Wall Street Rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma, though, stood out from amongst all the others I’ve attended. The May 13-14 event consisted of two days of music, vendors, motorcycle competitions, historical tours, and cultural experiences within the historic Black Wall Street area of Tulsa’s Greenwood District.

Most motorcycle rallies take place in summer and fall, and I’ve been to my fair share of them, from Sturgis to the National Bikers Roundup to local events. Each one is unique, creating its own culture, reflected in the attendees, location, and associated activities. Yet there are also generally crossover points that make them feel more similar than different.

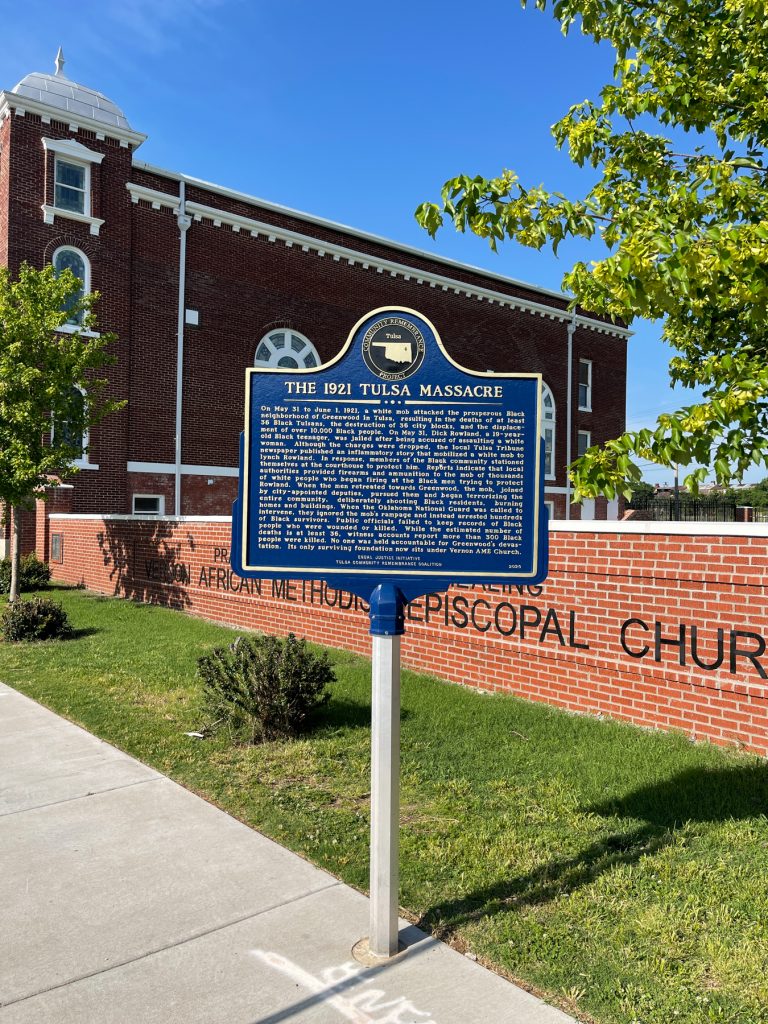

The rally was launched as a way to commemorate the history of Black Wall Street, which is known for the tragic 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, an event that, despite its significance and dire consequences, had been intentionally buried in history, escaping wide public knowledge until recent decades.

As described on the rally’s website, “Tulsa, Oklahoma’s Greenwood District was once characterized by bustling streets with hotels, theaters and doctors offices, restaurants, nightlife establishments and more. It later became known as ‘Black Wall Street,’ one of the most prosperous African-American communities in the United States. The creation of the powerful black community was intentional. In 1906, O.W. Gurley, a wealthy African-American from Arkansas, moved to Tulsa and purchased over 40 acres of land that he made sure was only sold to other African-Americans.

“On May 31, 1921, a white mob attacked black residents and destroyed homes and businesses of the Greenwood District, known as the Tulsa Race Riot. The incident is considered the single worst incident of racial violence in American history. The attacks burned and destroyed more than 35 square blocks of the neighborhood—at the time one of the wealthiest Black communities in the United States.”

As summarized by the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum, an incident between a young Black man and white woman in an elevator (an American Red Cross Disaster Relief Committee report) on the museum’s website says the young Black man, “on entering an elevator conducted by a white girl, stepped on her foot”) became the spark that “ignited a long smoldering fire.” Accounts of the elevator incident became more exaggerated as they circulated among Tulsa’s white community, setting off an out-of-control spiral. “Jim Crow, jealousy, white supremacy, and land lust, all played roles in leading up to the destruction and loss of life on May 31 and June 1, 1921,” according to the museum summary.

~~~

In addition to the draw of the rally, I also traveled to Tulsa to connect with friends from various parts of the country. We’re all bikers, many I’ve known for years, one essentially since childhood. I rarely get to spend time with them, so rallies like this provide an opportunity to reconnect, regardless of how “good” the event turns out to be.

The ride to and from a rally is part of the experience. Round-trip, my ride was 1,320 miles over three days, with unfulfilled hopes of catching up with other riders along the way. As with most trips, no matter how tired I am at the end, I loved this ride . After 13-plus hours of riding, I reached the Osage Casino, the location for the Black Wall Street Rally registration.

I pulled up and saw a sea of motorcycles gracing the asphalt lot—this was the moment I understood just how many people had traveled to support this event, and I knew these bikes were merely a small sampling of the full number of bikers who had made the journey.

At registration, along with the official pass to the rally, we received some merch, entrance to Greenwood Rising, the Black Wall St History Center, and admission to a variety of venues hosting related events. Already, this was a little more than what is normally included with standard motorcycle rally admission.

Beyond this, the rally offered a wide range of programming, such as outdoor musical performances, speakers, and vendors of items ranging from food to clothing to cigars. The motorcycle events included a parade and an all-female ride as well as sound system competitions, bike show, and demo rides sponsored by local dealerships. All this stretched along a three-block area, allowing the local businesses to take part, all in the same historic district that was once home to Tulsa’s thriving African American community.

This variety of activities created an environment unlike most rallies I’ve attended. The first noticeable difference was in population. As expected, there were bikers and “biker adjacent” visitors, garbed in leather and representing motorcycle clubs from across the country. But there were also cultural enthusiasts who came to celebrate the history of the people and the unequivocable “Blackness” of the event.

~~~

Few spaces and events truly honor Black culture without a sense of stereotype, pandering, or makeshift atmosphere, resulting in a celebration that seems like an act put on for visitors but that underneath feels disingenuous. In contrast, the Black Wall Street Rally environment was warm and welcoming across the board, and being in this place felt authentic.

As a result, visitors who weren’t part of the motorcycle community had an opportunity to experience Black culture from a historical perspective related to the area, while also connecting to the steadily growing subculture of Black bikers. Whether people were there for the HBCU Hour (HBCU is the acronym for historically Black colleges and universities), gospel performances, or the food, there was something for everyone, all stemming from the celebration of this historic Tulsa community.

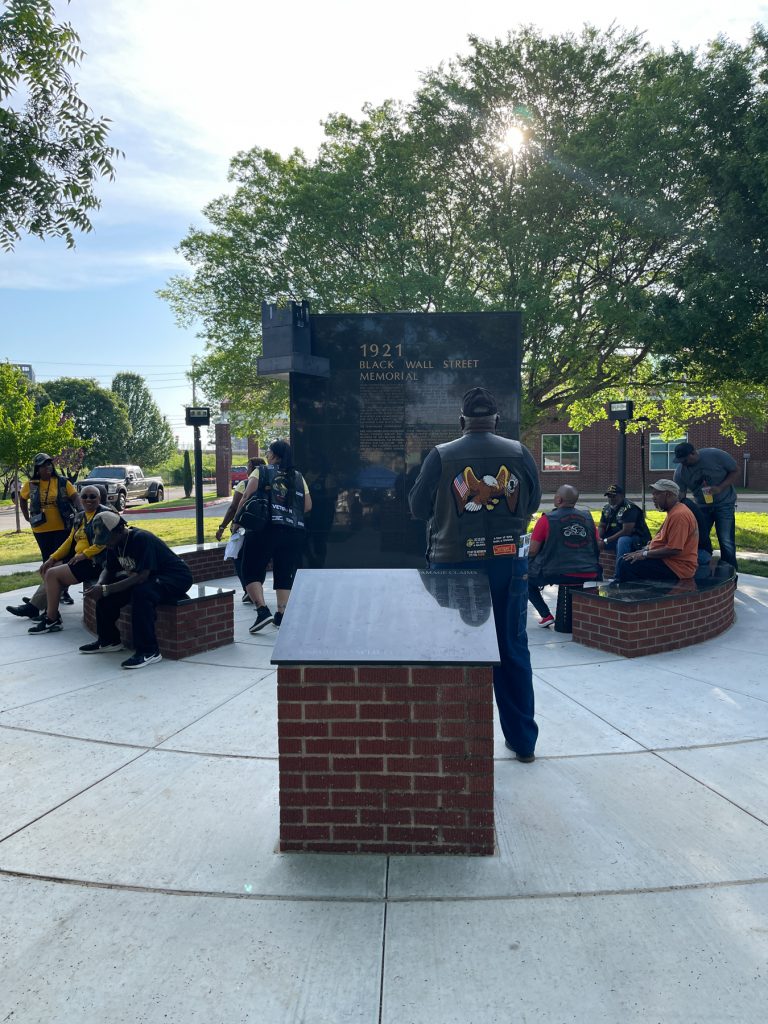

It’s this tie-in to the Greenwood community’s history that distinctly separates the Black Wall Street Rally from so many others I’ve attended. This rally celebrates the people and events that had made this a thriving community while also remembering the horror that resulted in as many as 300 deceased, along with 1,256 homes and 35 city blocks of businesses, churches, schools, and theaters burned to the ground.

Not only were these homes and businesses destroyed, a fact tragic in its own right, but the properties weren’t returned to their rightful owners nor was restitution given. Municipal and county government authorities at the time sanctioned, supported, and armed the white mob. Beyond the deceased, up to 800 residents were injured, more than 8,000 left homeless, and 6,000 detained in internment camps.

This blight on American history was the launch point of the rally, an event for remembering what had been inflicted upon this community, in this place. But there was also a secondary reason for the rally: celebration. The Black Wall Street Rally exists to celebrate the Greenwood District’s revival. The establishment of the Greenwood Cultural Center and Greenwood Rising, both centers for cultural experience and historic preservation of the area, as well as new businesses are a direct example of this revival in action.

~~~

The presence of families also separated this event from most motorcycle rallies. Not that you never see them at a rally, but here the families were present in order to participate in festivities that were joyous, informative, and educational. To me this was a defining distinction of the Black Wall Street Rally: it’s genuine atmosphere of inclusion, which extended beyond members of the African American population.

I had the sense that, particularly for the families of color, they were there in order to absorb something we as a culture had lost. They were reclaiming the past by steeping themselves in the values that still exist in the very foundation of this place. This event gave them the opportunity to engage and connect with the people, environment, all of it. In this connection was space that allowed for an unabashedly Black existence which so often can’t be found in white America. Watching a step show or hearing Maya Angelou’s reading of “Still I Rise” at the historical center provided moments of enrichment, not just enjoyment.

As I walked Greenwood Avenue, I took in the motorcycles and marveled at the detail and attention applied to the customized bikes and paint jobs. I viewed them against the backdrop of the murals adorning walls that survived the 1921 chaos and those erected after, murals that tell the history of this place and honor it through aesthetic expression. The motorcycles became strokes of paint adding to the already colorful spectrum of the Greenwood District, and it all felt appropriate, like it was always meant to be.

During my time at the rally, I was able to unexpectedly see friends made on the roads of my trips, reconnect with those already planned, and build new bridges with bikers I hope to see again soon. I laughed, shared drinks and meals, and rode side by side with people who had made this trek just like me. Over shared glasses of bourbon the night before departure, I changed my route home in order to bypass thunderstorms across the Midwest, knowing this assuredly meant an extra 614 miles of solo riding home to beat sundown. But looking back at the weekend, the ride, the rally, the experience, even this inconvenience was worth it.

I commend the organizers of this event—many of us who came this first year look forward to setting time aside each year to return and watch how the rally grows. While the impact of the loss of Black Wall Street continues to be felt generationally and socioeconomically, this event is another element of its recovery and its rise from ashes. The injection of income into the community, the time to celebrate and remember, and the chance to bathe in Blackness for a couple days inspire those who ride in. We ride back out filled up and fortified for our day-to-day lives.

Armon A. Means, Anthrow Circus's manager of operations and social media, is a fine art photographer and professor of photography living in Nashville, Tennessee. When not in the classroom or behind the camera, he's riding motorcycles, hunting down the best BBQ in the region, or doing woodworking out in his at-home woodshop. His work centers on ideas of cultural concerns, minority identity, environmental influences, and the notion of interconnectivity through shared experience.