View of the Horse Ceremony in front of the barricades. Photography was not permitted inside the camp.

Text and photos by Manuela Thames and Becky Schauer

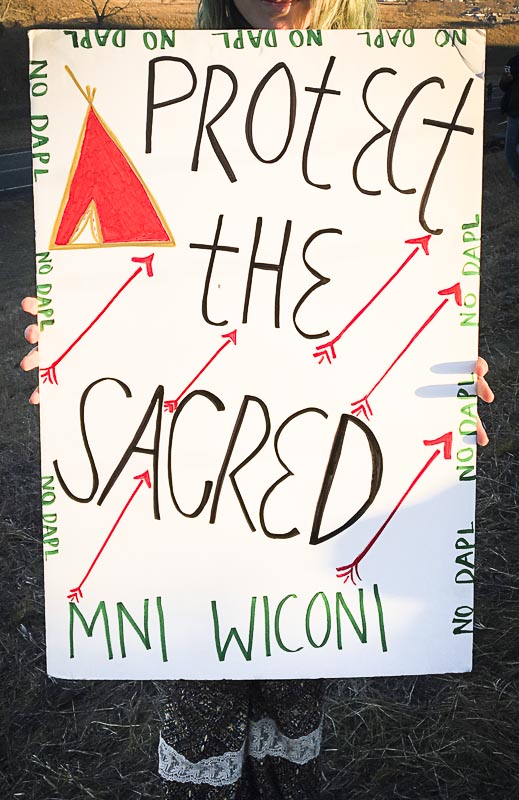

The specifics of the controversy over the Dakota Access Pipeline dominated news cycles last fall, but now we bring you reflections from behind the scenes at Standing Rock where our contributors learned much from their Native American hosts. Regardless of your position toward the pipeline, we hope you’ll listen and learn universal lessons along with Becky & Manuela.

It was evening on November 11, and we were driving westward on I-94 past golden emptiness. None of us had really slept for the past three days or so. The events from the previous Tuesday still hung thick in the air, like a somber dirge, heavy in the hearts of each one of us. The entire fall had been strange, dark days, to say the least, with angry words flung across social media lines, all having to do with politics. Many we knew felt physically sick after the election; we understood and admittedly felt the same.

Now here we were driving as the day faded away. We were headed toward an unfamiliar destination, filled with uncertainty and fear, both for what the longer-term future held and for what would happen in the upcoming weekend.

Feeling inadequate and grieved by a history riddled with oppression, as well as humbled by the past, we wondered as we headed toward Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Land if we really had a place in this indigenous effort to save the water. For preparation, we had read the elders’ instructions on how to conduct ourselves as guests when we arrived: we were to come with a good heart, one willing to listen and be silent; to come upholding the Lakota values of prayer, respect, compassion, honesty, generosity, humility, and wisdom; and to come with an awareness of how colonialism had wounded and affected all of us in different ways. We didn’t really belong there, but we were welcome anyway.

ARRIVAL

It was midnight or so by the time we arrived at Oceti Sakowin Camp in North Dakota. The black night sky was illuminated with thousands of flecks of light, and the smoky air filled our nostrils with the scent of burnt fragrant sagebrush. The nervousness inside our car was palpable, as our hearts pounded fast and rhythmically with the faint sound of drums. We had to pass through security to enter the camp and were questioned about why we had come. Our reply, which seemed strangely scant and insignificant, was, “We’ve come to help.” Somehow it was enough, and we were waved through.

The entrance into camp was lined with colorful flags representing the various tribal nations. Looking to the right, we could see an endless field of teepees, tents, and campfires, and to the left, fairly close in proximity to the camp, standing menacingly in the night sky, was a line of floodlights, bright and bizarrely out of place. We were later told thatthis was where the pipeline stood. Somehow the realness of those terse words cut deep, awakening us to the reality of what resistance against greed and power looks like. We went to bed with this heavy on our hearts but relieved and eager to be at camp.

FINDING BELONGING

As morning came, we could see that the camp was filled with people from all over the world united in this effort, yet despite several thousands of them, it was astonishingly quiet, clean, and organized, and most of all peaceful. The Natives called it a resistance camp of prayer and ceremony, making a clear distinction between their self-identified role as protectors and the name they were commonly given in the media, protesters.

Help was needed as there was a lot of work to be done. Among the many tents and teepees in the camp were larger army tents serving a variety of purposes: kitchens, dining halls, donation centers, media aide, and medical care. We found ourselves sorting through medical supplies, organizing hundreds of cans of beans, going through boxes and boxes of donated toiletries, and chopping vegetables. Everything was shared—food, work, and purpose—making it really easy to jump right in. As we moved from task to task, we soon transitioned from feeling unsure of what to do to having a place and a sense of belonging in this movement.

SACRED CEREMONY

In between our various tasks, we were invited and even encouraged to attend some of the sacred native ceremonies, many of which left lasting impressions on us. One of them we inadvertently happened upon.

The day had already been long, and it felt as if a week had past. The early evening sky hinted of shades of yellow and gold, reflecting the sun’s warmth on the gently flowing prairie grass. We decided to walk outside of camp, along the roadside and adjacent high hills. From the hilltop, one could easily view how expansive this collective movement had become.

Down on the road sat a line of native people praying. Behind them another group sat in a circle, mostly white supporters whom the Natives referred to as “fellow warriors.” Further down the road, about 100 yards or so, was a barricade, and behind the barricade were two neat rows of at least 20 squad cars, 10 on either side. The stark, incongruous image of these two colliding worlds seemed like a throwback from some civil rights documentary. Yet it was a reality, our present history, and we were all bearing witness to a small, momentary part of it.

While we were taking all of this in, several young Lakota men rode up and then down the hillside on horseback. They seemed free and appeared to be joking with one another. They ended up down by the road, lined up on their horses in front of the other water protectors. Out of curiosity and a desire for solidarity, we slowly followed. Several others did as well.

WORDS TO BE REMEMBERED

One young Lakota man spoke up. What we heard that night was something that none of us will ever forget. It would be impossible to repeat the words as eloquently and beautifully as they were spoken. What we remember was this: “My brothers, this is a moment in history…It is the first time in over a hundred years that the seven council fires have come together in unity…My grandfather told me that we should ride down together, and so we ride, in peace and not violence…This is our legacy, my brothers, and one day we will look back on this time with pride and smile…we are here protecting the water and Mother Earth…our allies are all of these people who have come from all over to stand alongside us….and we pray for them and the water, but we also need to pray for those on the other side, those who oppose us. They have families too, and they are just doing their jobs…”

As we walked back to camp, these words resounded in our heads. Words that we didn’t necessarily feel toward the police and Dakota Access Pipeline workers after being there for only one day were upheld by these young Lakota men whose ancestors had historically faced this kind of opposition. It was happening again, but this time we were witnesses of the prayerful, peaceful agenda of those who sought to save the water and protect the earth.

YOUTH COUNCIL LEADERSHIP

Later that evening we attended another powerful ceremony led by the indigenous youth council who had been at Standing Rock from the very beginning. The youth were among the first to stand up for their rights for clean water and a clean earth. The elders had encouraged us all to attend this ceremony. So several hundred of us joined the youth at one of the sacred fires adjacent to a teepee which was gifted to the youth by the elders; the gift demonstrated the deep respect the elders had for them.

The goal of this ceremony was to pray and march in silence to Turtle Island, a small hill and sacred burial site situated right in the middle of the pipeline construction. Turtle Island was about a twenty minute walk from camp. The Natives had undertaken countless peaceful actions at this site. Stationed upon the top of the hill were several armed policemen who stood day and night, securing the site, preventing the Natives from going up to theirown sacred burial grounds.

Just days prior to this ceremony, several members of the youth council had gone on a peaceful action to Turtle Island, which had been accessible only by crossing a short wooden bridge over the Cannonball River. But the bridge had been taken down by the police in order to keep Natives from accessing the ancient site. Because the bridge was gone, the youth council members had attempted to cross the river by wading through inhospitably cold water to pray and talk to the police. But as they neared the land on the other side of the river, they had been confronted with pepper spray and rubber bullets. Some of these young Natives were barely 18 years old, yet they had remained in the water, unarmed, letting it happen, while praying for the health of their water, their ancestors, and their enemies.

And now they wanted to go back to heal the trauma inflicted from both sides and to pray. It is difficult to describe the heartbreak that was distinctly visible in the Natives’ eyes and voices, but it evidenced a deeply embedded pain as a result of others’ ignorance and disrespect for the sacred. So on this cold, mid-November evening, we prayerfully marched in solidarity with them, each of us holding a burning candle in our hand while listening to the quiet chanting and drumming. By now the sun had gone down, and as we approached Turtle Island we could see the silhouettes and shadows of a number of police cars and officers lined up on the hilltop.

The ceremony begun, but because there were so many people, it was impossible to get close enough to hear what was being said. However, after only a few minutes we were instructed to turn around and prayerfully walk back to the camp. Upon leaving Turtle Island, we noticed a sizable fire on the other side of the river. Several of us stopped and looked over to see what exactly was going on.

We could feel the tension, and people were beginning to get nervous. It was unclear how the fire had started, but it seemed intentionally lit. Young members of the indigenous youth council kept walking and encouraged us to do the same. One of them repeated these words: “Do not get irritated…do not turn around…stay focused, stay in prayer…we have our own light in our hands. They want to provoke us, but this is a prayer march and we need to stay focused. Pray for them, forgive them…We are being peaceful…”

Once again, we were struck by the powerful messages of peace, prayer, and forgiveness.

PLACE OF HEALING

When we had left home, only two days prior, we had come from a place of dissension and anger. At Oceti Sakowin Camp, we entered into a place of healing. We didn’t seek healing, but it was an obvious by-product. Our initial fears almost immediately melted away upon our arrival.

Moment by moment, people were living out their values with complete conviction and for an honorable cause. Their humble plea to the “Great Spirit” was always the same: it encompassed an awareness of the sacred and deep interconnectedness of all of life. We were the fortuitous recipients, quietly listening and breathing in this wisdom.

We realize that this is only our brief account of a moment in time at Oceti Sakowin Camp. The more comprehensive and richer accounts of what actually happened at Standing Rock should be heard from the Native Americans who lived there day in and out and started this remarkable, indigenous-led movement. They have cultural perspectives and experiences that are different, and perhaps more accurate, than our own, and this is their story to tell.

We honor that, and only wish to say that we were witnesses. We thank the Native people for welcoming us with overwhelming kindness as family members, not strangers, and for paving the way by showing the rest of the world how people of diverse backgrounds can come together in complete unity, peace, and love. Our hosts had been protecting the water for months forall of us, carried by a quiet, uniquely powerful strength.