Dawn, Emily, and Allison

STORY AND PHOTOS BY JC JOHNSON

A good black and white photograph has a pure black, a pure white, and every grey in between.

My first photo class, my professor taught me that a good black and white photograph has a pure black, a pure white, and every grey in between—a mantra I now repeat to my students. Just like with a cause that rallies people to the streets, a photograph is exposed with different variations of light in order to become a successful image. A good photo needs contrast. Without contrast, the image is flat, boring, and unmemorable. But too much contrast sacrifices image quality with loss of details and information; it usually means you didn’t do it right. In other words, the presence of only a small amount of grey means you didn’t consider where the light hits the important parts of the image.

The Women’s March on January 21 was a lot like a photograph to me; it was full of black, white, and lots and lots of greys. But it’s the greys that are easiest to miss and gloss over, no matter who is looking at the March’s image. For many people, the issues being addressed at the March were and are very black and white, and the greys aren’t even considered. What many participants and observers viewed as a positive, inclusive moment was met with anger and disapproval by other observers viewing the scene from a different perspective. For many representatives of either “side,” it wasn’t worth considering another point of view because they assumed those points of view represented the complete opposite side of the spectrum—they didn’t consider where the light hits to allow for a spectrum of greys.

I marched for the people who couldn’t march, the people who have marched before me, and for the people who wholeheartedly disagree with the March.

Allison

Nashville, Tennessee, is a burgeoning southern city that is a combination of old and new. Every month, thousands of new people move to a changing Nashville, and it finds itself a city wrestling with its identity. It is one of only two blue congressional districts in a predominantly red state, and the tones and values of the city vary as widely as its kaleidoscope of old and new residents.

Curious about how these variations played out among people from Nashville who participated in the Nashville Women’s March or the larger march in D.C., I posed a question to some of them: “Why? Why did you march, and can I photograph you?” I wanted to see some of their greys. Where did they see light exposing this story?

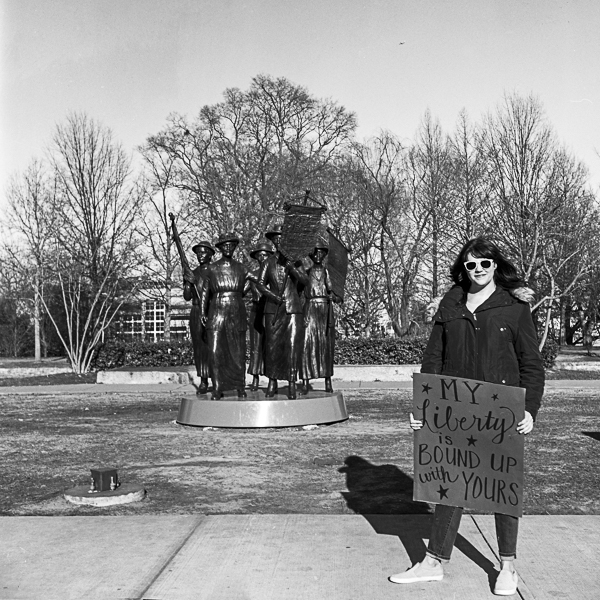

n their responses, I met a group of people asking others to consider all the values, not just any one specific issue. For their photographs, I instinctively asked to meet in front of the new Nashville suffragette memorial. By coincidence, we stumbled upon a group from the League of Women Voters of Tennessee with a similar idea. I introduced myself and talked with them; in five minutes strangers became friends, partners, and sisters. It was clear that each woman had her own reason for marching, but they all marched together. To say it in photographer-words, each woman may have been looking in a different direction, but the sunlight was shining on each face from the same place.

It wasn’t worth considering another point of view because they assumed those points of view represented the complete opposite side of the spectrum—they didn’t consider where the light hits to allow for a spectrum of greys.

A world without contrasting extremes would be flat, boring, and unmemorable. Some aspects of life will always remain black and white; we can’t develop an image without those two values. However, by holding too hard to contrast, we will find ourselves either surrounded by empty white space or blind in the dark, black areas. Being contrasting is what makes us interesting as human beings, it’s what catches the eye first. But it’s our ability to consider the light and create a final image with all the greys in between that makes us special. Keep the black and white, but expose for the greys.

“I marched for my mother, or more specifically for the woman she taught me to be – one that doesn’t see race or gender or sexual orientation or country of origin and think anything less or greater because of it. I marched because she always made me feel like I could be anything, and I want to pass that message on to all of the girls and women of the world, regardless of where they come from, what they look like, what gender they were assigned at birth, and what they believe in. Until that message is a reality, I will be fighting.”

Erin

JC Johnson, Anthrow Circus's creative director, spends most of her time as a photography and arts instructor in Nashville, Tennessee. She is often overwhelmed with wanderlust, photographs internationally, and has a passion for travel and study abroad as both an artist and instructor. Her photographic work makes associations to childhood as well as to the nostalgic and the whimsical. Common themes in her photography include European architecture and history, fashion, travel, toys, and miniatures.