FICTION BY DENISE CAMPBELL

IMAGES BY KAMI RICE AND JC JOHNSON

“Wake up, Indigo! Time to start this journey you come here for.”

Aunt Mercie’s singsong call rushed in with the sound of the rooster crowing. We woke to a washed-out, downcast morning. But by the time Salome and I loaded the crocus sacks of groceries into the back of the pickup, the sun had put in an appearance. She’d landed in Kingston two nights before and had to make the trip with me to visit my sisters—Samira in Bog Walk and Claudine in Lional Town. Salome and I had grown up on the same street in Norbrook, in the hills of Kingston, and gone to high school together before attending universities in different parts of the world. Even so, we were bonded friends for life in the way Catholic high school compatriots often are.

Over Aunt Mercie’s stew peas and bottles of Ting, Salome had helped me sort and separate the food and clothes earmarked for Samira and Claudine, making sure each got their share of flour, rice, cornmeal, cooking oil, and household items. Though we’d kept in sporadic contact, it was more than five years since I’d seen any of my sisters. For all her talk, I hadn’t seen even Dominique in that time. Through letters, holiday cards, and every-now-and-then phone calls, I had just a vague sense of their lives, that there was a coterie of nieces and nephews for whom I’d packed discmans and CDs I thought they might enjoy.

After we’d all turned in at Aunt Mercie’s last night, Dominique had called to say she would arrive first thing in the morning to come with us for the drive to Samira’s. Trevour, Aunt Mercie’s trusted companion, would drive Dominique, Salome, and me to Bog Walk. He’d been with our family ever since I could remember, had driven us across the island countless times, and knew most of the country roads through Jamaica.

From Bog Walk, the plan was to meet Adassa at her niece’s bake shop in Old Harbour, then together we’d make our way to the address she had for Claudine in Lionel Town. But for our father’s insistence and the folly of a “peaceful life,” I could not for the life of me understand the need for our wicked stepmother’s insertion into this fairytale journey. Through a series of increasingly bewildering excuses, she’d avoided handing over Claudine’s address itself, making things more complicated and keeping herself part of the mix. Initially, she’d suggested that I meet her in front of Spanish Town hospital, but Aunt Mercie had put the brakes on that idea.

“Yuh mad! Spanish Town hospital wid American grocery? Your mother would crucify mi! One look in de van wid all that food and people will come from far and wide to rob yuh. And Adassa know dat!”

It was well over a decade since we three half-sisters had all been in a room together. Even in the year before I’d emigrated, we’d seen almost nothing of each other. Years ago our father Capo had mentioned that Claudine was a physician’s assistant in Moneague, where her son’s father lived. We’d spoken several times each year, but then I’d called on her birthday and the number was disconnected. That was six years ago. Updates had come third-hand from Adassa until they’d trickled to nothing.

There were six of us now with these last two. Daughters all. At Capo’s insistence, the fifth was to be named Beatrix, after Aunt B, his mother’s sister. When I was born, he’d wanted that name for me, but my mother had rejected it as antiquated. The sixth daughter, born less than a year later, was named Micah, not from the Bible, but from a character in a movie Adassa liked. This sixth girl confirmed a running joke that if a young girl presented him with a male child, we’d all know it couldn’t be his; that he was a reverse Father Abraham, spewing all girls and no boy to perpetuate his name.

Samira and I were six years apart, the third and fourth of Capo’s girls, all with different mothers. But our age difference had been almost non-existent. She’d told me things the girls at her all-age school did and about working in the market with her aunts and mother. I was the first one she’d told about getting her period when she was in the tub in the backyard, and I’d recounted to her what the school’s guidance counselor had told us about it. I’d given her all my science and math books—even the ones I liked best. We’d been left together many weekends at Capo’s—with Adassa or some other woman a reluctant caretaker—when he’d gone off with a new girlfriend or with other friends to overnight beach parties on the North Coast.

Once, after an argument with him, Samira had demanded to be taken home, and when he’d refused, she’d thrown her knapsack over her back and taken off the second he’d left the house. She hadn’t made it back to her mother’s tiny house in the country until after dawn the next day. It was one of the few times I’d seen him truly angry, and I’d had a grudging respect for her after she did it. But we didn’t see each other again for months and I had to wait to tell her. The last time I’d come with Capo to see her, they’d spoken from either side of the fence—she from inside her yard and him on the outside with his back inches from his newly polished Cadillac. The bumper reflected their ghoulish caricatures in the moonlight.

“How you doin,’ Samira? How you makin’ out?”

“Fair to middlin’, Missa Wade.”

She hadn’t looked at him, not even at the top of his head, but instead turned her face sideways and addressed something at her side. They’d spoken about things I didn’t understand, and later Adassa told me that Samira was pregnant and would have to leave school. I’d cried the whole night without knowing why.

Months after I’d started college in the U.S., I’d saved up and sent Samira a barrel, taking a curious delight in forfeiting weekend movies and evenings out with friends to pack and ship it. I’d included the usual necessities but also some of my favorites I thought she and the children might enjoy. After the barrel had been delivered, I’d called excitedly, “Did you get it?”

She’d greeted my excitement with a symphony of complaints I didn’t know what to do with.

“Mi haffi pay de man extra fi go up the hill.”

“Is not enough flour and too much rice.”

“Some things thief out of it ‘cause it looked only half full.”

“Wha’ ‘bout cereal an’ shoes foh de chirren dem?”

The following week she’d called to know about help with a down payment on a housing trust lot that had come up, and after that, she needed help for a fridge from the Courts store. Aside from Western Union money sent sporadically and unexpectedly over the years, I’d given up. She must have too: She never wrote or even called collect. None of the promised pictures of the children ever arrived.

Now, six children and four men later, I wondered what of the old Samira I’d recognize, what was left. We drove through Spanish Town, a quarter mile past Bog Walk, and into the tucked away hamlet she and her mother and grandmother had lived in all their lives. It was a slow, meandering town whose glory days had never quite come. The matchbox house was hitched on a tiny hill and was the same one I remembered from past visits. Unless they’d made major changes, it consisted of two small rooms no larger than the cubicles at work. The front yard looked like it had been razed after the house’s occupants fled in a mad dash for survival. The lone hold-out was a white rose bush in the first blush of bloom. It flourished in a dirt patch at the side of the little house, its perfect petals stretched just outside the rusting fence, the one enchantment in the dismal, desecrated yard. In the back, farther up the hill, smoke from a coal stove streamed from the doorless, lean-to kitchen. I wondered what they did when rain came in torrents as it often did in these parts.

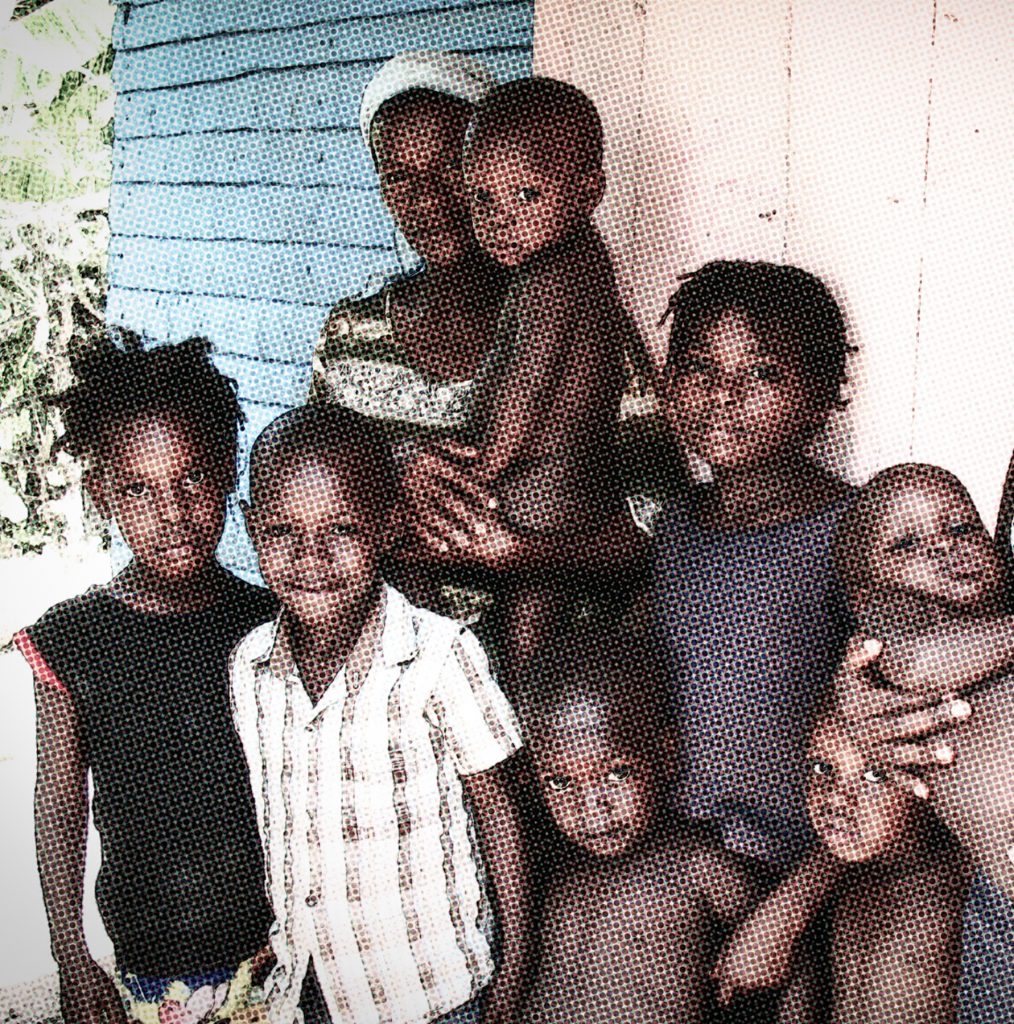

Against the fence, arms folded, with a broad, red band across her forehead, stood Samira, a daguerreotype version of the girl I’d last seen. In the calf-length, three-sister skirt and puff sleeved blouse, she looked like a pioneering school teacher. Behind her stood a rag-tag bunch of children, with rambunctious hair, sturdy limbs, and broad smiles. A grubby, off-white dog lazily licked its privates, then yelped a greeting. So this was how it had all tuned out.

“You really come fi true! And early too!” One hand sat akimbo while the fingers of the other fluttered at her mouth. “Never believe I’d set eyes again. And look who yuh bring? Is where yuh find her! God can come down from heaven now!”

“Samira? Is you?! Never think I’d see the day!” Dominique lit out of the car before it came to a full stop.

They hugged briefly and Samira laughed, “Long time now anybody call me dat. Dainty me name now. Is where Indigo find you? You look good!”

She still had that tentative, lopsided smile and the dimple in her left cheek. For a moment, I felt a burning shame and sadness that I had abandoned her to this. That while I’d been developing plans for clean water dams in foreign cities and dreaming of Blue Mosques and Brazilian cherry wood for wood carvings and imbibing brunch at the Columns, here sat my flesh and blood.

“I can hardly believe it’s you! It’s a shame how long it’s been.” I ran my hands over her hair and held her to me even after I felt her hand feebly pat my back.

The children carried the bags into the tiny front room, dancing around us as if they’d caught Santa in the act. There were eight in total; five were hers and the others belonged to assorted sisters and aunts. The living room brimmed with various iterations of religious images. Jesus, Mary, and a host of saints were paraded shoulder to shoulder against every inch of wall space. Plastic figurines of saints in repose dotted the tiny wooden table and the ancient breakfront. Between images of Jesus and Mary was a framed picture of the eldest daughter, Althea, at her high school graduation and another at the teachers’ college she attended. Bunches of flowers, bougainvillea mostly, sat in small plastic buckets around the room. In the back room, camphor was burning, and the scent wafted into the front room.

Around bottles of the Shandy and Ting we’d brought, we eased into a light camaraderie, trying to fill in the blanks from all the years that had slipped away. After bustling about for assorted biscuits and papaya, Samira eased onto the lone hassock in the room, leaving the sofa for us.

Even after all the babies, she still retained something of her swimmers’ physique. Yet she sat down heavily, then seemed to fold her shoulders into herself, like origami, as if hoping to go unnoticed or perhaps to disappear altogether. No signs of those fingers that looked like they belonged on a Steinway playing in Carnegie Hall. Now the knuckles were knotted and calluses had taken over the soft places of her hands.

We swapped stories and pictures, and four of her children were paraded in front of us. Our peals of laughter and loud exclamations spun out in the little room, and it was easy to imagine it was a reunion of true sisters.

“Remember dat time when…”

“But don’t forget how we…”

After the second child, she’d started taking in sewing and darning, she told us, using the second-hand Singer sewing machine Capo had bought her. Then she’d had a stint in trade school, but the men and the babies had kept coming, and money was always low, and after a time she’d given up to the inevitability of fate. The second to last child, a girl of about five, shone like an exquisite emerald among the rushes. She looked up at me with large, liquid brown eyes, and I wanted to scoop her up and whisk her away from all of it. Do it! Why not? a voice demanded.

Verna, the second daughter, waded into the room, a baby of about eighteen months bobbing at her hip. She promptly placed him onto my lap.

“Dis one name Frederico. Haffi be the last. Can’t tek no more.”

A dusky, curly-haired, dimple-chinned thing, he cooed and spit as I fed him softened water crackers. I tried not to squirm against the soggy cloth diaper and was relieved when one of the children took him away for a nap. The other boy of about ten watched us with fierce, jaundice-glazed eyes. Every now and then, a small smile relieved the tension on his face.

We knew from the scurry of the children into the back room—and the curtain of silence that followed—that he’d arrived. His long, gangly legs filled up the tiny door frame. Against them hung his machete crusted with mud and something else. Among us, Dominique was the only one who didn’t flinch. Instead, she leaned back against the lumpy sofa, one arm draped across its back, her face assessing, as if waiting to hear the punch line of a bawdy joke.

“A him dis to rawtid? Is coolie yuh mek put ring pon yuh finger? But yuh nuh easy! Is beyond time yuh come outta this bush, m’dear.”

I nudged her hard and she chuckled unapologetically. “Mek me chat!”

He came from the farmland with the other men who worked the ground. He looked us over, then dusted off his boots without a word of acknowledgement. The room waited until at last he gave out, “Where mi tea and coconut water?”

His hair was long, inky black, and silken. It wound down his back like the serpentine staff of a prophet. The thick bush of his beard was held together at the end with a tired rubber band. A tiny crocheted red, gold, and green hat perched atop his head like a steeple.

I knew in his mind he was wondering where the men were and why these men-less women congregated in his house.

“Ah mi sister dem,” Samira gave out, watching his face and hands. “Dat one come from foreign—where?—New Orlins. Dis one,” she hooked a tremulous finger in Dom’s direction, “live a Kingston. Dis is McKenzie. Everybody call him Bunty.”

He wiped off the machete with a crumpled newspaper and told the boy to put it in the kitchen behind the coal stove. Hellos all around did nothing to break the ice, and he made no move to shake our hands. His grudging smile came like tiny ripples on a pond, and he turned his face from ours even as his mouth said, “Please to meet you.”

She’d met him at a tent revival meeting in Linstead where’d he’d just been passing through. She’d been ensnared by the dark ropes of his hair. When the first blow had come she’d still been punch drunk with love and had mistaken the explosion of light in her head as stars in her eyes. I imagined her running through the fields, the hard slap of her feet against the ground, sweat and tears and everything else running into her mouth—and wished for a moment that I were a man.

When had she given up, I wondered? When had she resigned herself to this cage, agreed to let whatever she yearned for dissipate through her fingers, to die stillborn? Easy to say, “Not for me, smoky evenings around a coal stove,” fingers smelling of kerosene from the wick of the fading lamp, hands calloused from steaming plates and blackened pots, doling out food with a subservient smile as I waited for the men to eat first. Mine had been the paved path of first-in-class, best-in-show, gold star for science. Neither choice had been entirely ours to make. I looked into the steel cages of his eyes and the unyielding chords of his neck and hands and knew why she was afraid of him. The children bundled together at the doorway between the living area and the bedroom, silent, watching. If one fidgeted, an older one swatted at them and all grew hushed.

“So where oonu husband? Nobody nuh come wid husband? Can’t believe is so far dem mek you travel on you own,” he asked now, an attempt, I supposed, at civility.

He was living in the 1920s and I had no patience for it. How the hell did she live in this back-ass ward, armpit of purgatory? I wanted to shake her until her teeth rattled. Wake up! Smell and taste life beyond this town!

“Yes,” I answered glibly, “they let us out these days.”

We stumbled about, reaching for safe conversation. Salome was unusually reticent and, after a while, set out with her trusty camera to take pictures of the surrounding country scenes.

“Ladies,” he began, “did you know that Jesus is the Way, the Truth, and the Life? Have you declared Him yet, sistas?” He walked over to the ancient bureau in the corner, rooted around for several religious tracks, and placed them at the edge of the table.

Declare Him to who, I wondered.

“Awright, Bunty. Dem sey dem will send a likkle money next month,” Samira offered timidly.

“We know things rough and we want to give Samira a hand, especially with the kids,” I said.

He interrupted, “Is Dainty she name now.”

“Maybe help get them on some kind of schedule that would help with school and food,” I suggested carefully.

He nodded his agreement and caressed his beard with dirt-encrusted fingernails that made me queasy. “Hhhmm, hhhmm. Each one help one. So me see it. So de Bible sey. Long time me tell call har people dem a Kingston.”

“It would be good if the children could be in some kind of structured school environment. Like Althea.”

“So how she would get the money?” he asked, pretending to mull it over.

“Western Union or something,” I offered impatiently. “Whatever’s convenient and in town.”

“Well, if you want, you can put it in my name and I can pick it up and give her. Mine o’ I nah fast in oonu business, I just tryin’ to help out a situation.”

Dom and I exchanged horrified looks. Clearly some ganja had gone to his head. “Why can’t she control it herself? What? She can’t read and count?” Dom demanded.

“Dainty don’t have ID fi pick up money. So why yuh don’t give her in her hand now,” he suggested slyly. “She know is for all of us.”

“But where is her ID?” I asked, puzzled. “Something with her name on it?”

“Me know har name, wha’ else dem need?”

It was too ridiculous to be debated and I didn’t push it, afraid Samira would pay for it later in ways we didn’t care to imagine. We stepped outside for a spell, needing relief from the saccharine fragrance of the flowers that intermingled with the stuffy, indefinable smell of the tiny, cluttered room. Who knew despair smelled like bougainvillea? Down the track next to the little house we trudged toward the wasted fields with their dwindling crops. One of the younger girls—no more than seven—rushed into my arms and hugged my waist as we walked.

“So what you do for money now?” I felt like Salome with one of her interview subjects.

“I used to plant pimento and ginger, help the banana farmers wid dem crop, but tings dry up now. Hotel dem don’t buy local produce no more, sey dem haffi buy from cheaper foreign people. Banana was green gold, now it mash up. We too expensive for our own good.”

The genius of the globalization machinery—it made my head hurt with anger and sadness.

“What about work in Spanish Town? Take a computer class.”

“Who will take care of de children? My mother can’t keep dem all the time an’ everybody else have dem own ting.”

She shook her head. “I sew, wash sometimes. I used to make T-shirt with the press print on the front, but people not money on it and it cost too much to buy the pattern in Spanish Town. Plus, people prefer buy from the haggler wid goods from America or the small islands dem.”

“Why don’t you come town?’ Dominique urged. “I can set you up with a little job so you can help the kids, help yourself. Yuh aunt or one of yuh friends can’t keep the chirren dem likkle bit? The two older ones can help.” She looked around. “No use sacrifice everybody to this.”

“Me ‘fraid,” she said simply.

“What yuh can ‘fraid of more dan dis? So what you going to do? Stay in it? Make them eat the same bitter sorrow you eat? What you going to tell them when they get older? Or you’ll just let them get used to this?”

“I don’t know, I don’t know.” She wrung her hands and looked behind her.

Nothing I said or promised would change even an iota of her life unless she wanted it to, but I said it anyway. To her and the Universe. “I’ll help. If you want something better for your children, I’ll help.” I paused then added, “But no more babies, Samira. Please.”

She smiled sheepishly. “Couple of months ago, no blood come end of month. When I check it out I say, ‘No boy, can’t go up to that again.’ This one would make seven. One weekend him go revival, I find Ms. Lillita and we go bush and dash it way. Momma say it nun fair to do data to ‘im. Sey I should have out all de babies God intend.”

“Stop the foolishness and take care of yuhself! Sometimes you have to claw your way out of the muck, year! We never lucky to get anybody to give a hand so it leave to yourself. Claw your way out even if you have to take out ‘im eye!”

It was hard to say how much penetrated enough to make a difference.

“One thing, though, neither of us is going to send money to him, so the least you can do is get your own identification. Jesus, Samira, don’t give yourself over so completely, for Godsake!”

She smiled wanly. “So Althea say too. How Missa Wade?”

“Sick,” I said matter-of-factly, as if I were delivering the weather. What was the use of saying anything else? What was she to do?

“Oh yeah?” She scratched her elbow absently, and the sound like chalk on a board set my teeth on edge. “Sorry fi hear.”

“So it go,” I replied.

“I used to go look for him ‘bout every two weeks, bring him fruits, sweet potato, coco and such—when I have it. ‘Im tell yuh? But one time I go an’ ‘im cuss me off in front some stranger at de hard.” Her mouth twisted. “Embarrass me, y’know. Cause dem tink me nuh ‘ave no sense or pride. Me is a big woman! Adassa, she put in har two cents, tell me how nobody like nutthin’ too black.”

I winced. “In front of him.”

She nodded and slapped away a mosquito, “You know from long time she push it, sey my mother give Daddy jacket, sey me nuh fi him pickney.”

Dom was incensed. “Mouth make to say anything! Always a push her own agenda. You can’t mind that. You look just like his father sister, Samira, so Adassa can say anything. She vex she couldn’t have baby fi him.”

“Long time dat now, but I don’t go back since.” She looked off into the field. “Hope ‘im awright though.”

There was no use offering consolations for any of it. For in this town and all the crevices like it, emotions are not hard currency. There was no value in longing or nostalgia or regret. Everything costs in real currency, and when the lights and water are off and the baby can’t breathe and the ground is unyielding but the rent man is coming tomorrow morning, what good is longing or reconciliation or if-onlys? It came now why I’d cried. She among all of us needed saving the most. Even then I must have surmised that if she didn’t get a hand up and out she’d fall headlong into the murky abyss that was familiar territory for girls like her from town to country. Hatred stirred in me then towards him, a useless, passionate hatred that only a conversation with God could ease.

Salome rejoined us from her photo wanderings, and when we returned to the little house, they brought a loudly protesting fowl that was to serve as a noonday feast in appreciation of our visit. The scrawny thing strained against the thin, red string twisted around its neck and made such a ruckus.

“No chicken for me, thank you,” Dom pronounced in a stage whisper. “One helluva shittin’ temper gon’ tek everybody dat eat it, way how dis ya fowl a carry on!”

I recalled thrilling visits to the country capped with late night sessions in the back of the farm or someone’s backyard. Sometimes it was a Nine Night for an elder who’d passed. The vicious, dispassionate neck-wringing of a favored fowl, its body careening wildly in search of its head. Then the long arc of scalding water and seconds later the acrid smell of blood and feathers, clawing and thumping against the lid of the Dutch pot as it writhed against the clutches of death. I looked at Samira, her shoulders hunched in, unresisting against the strain of her own red string. When had she stopped, or had she bothered trying at all after the fathers of the first two girls had lit out for parts unknown with prospects and resources dwindling? Even without knowing they would have to do without to afford this feast, I wanted no part of it. I told her I wanted to buy her a goat and fish too if we could get some. She sent the eldest girl to the community man who sold both.

As we prepared to leave, Dom moved towards Bunty. Her smile was flirtatious but her eyes were wintry. They were sandwiched between the narrow, decaying door frame, and I watched in horrified fascination as she leaned into him, proffering several folded bills. I opened my mouth to demand, “What the hell?” but nothing came out. His smile stretched like a lizard’s and his hand eased up between them. But with his fingers a hair’s breadth from the cash, she suddenly whispered something. His face went slack like a cobra victim and his hands fell to his sides. She tucked the bills into his front pants pocket, then patted it.

“What was that?” I asked when we were outside.

“Not a thing.”

We left amidst promises and hopes of staying in touch, all the while praying we wouldn’t fall prey to the indelible pattern of this perverse version of sisterhood we knew. The image of the children waving from the dirt track stayed with me, and the soft feel of the little girl’s hand in mine, tugging on my sleeve, was ingrained on my memory.

In retrospect, we should have seen the pandemonium spiraling towards us like a monsoon. Should have noticed the men’s coiled watchfulness and distracted greeting. The play had been set in motion well before we hit that dead-end street and the van stalled on the speed bump. But buoyed by the camaraderie and promise of our visit with Samira, we missed all the tell-tale signs. Even Adassa had cooperated and gave me her niece’s address in Old Harbour, a halfway point on the way to Claudine’s place.

“Pass the likkle square and stay to de right. Look for Sleaveright Circle. Just ask anybody for number twenty-one. Can’t miss it—full of fowl and pickney.”

Then the niece had gotten on the phone to repeat the directions to Trevour again.

But doubts circled forty minutes in, after we’d entered Lionel Town. Despite following the directions to the letter, no square appeared. No one had heard of Sleaveright anything. All inquiries were met with a screw face, a head scratch, or both. Passionate, frustrated debates about whether we meant drive, avenue, or lane raged among passersby we asked; speculation that it might be a town his cousin worked in or where her father-in-law hailed from. As we drove from one dead-end to another, we called the niece, but no one answered. Text messages too went unanswered. At last, a young boy pushing a cane cart hooked a thumb behind him. “Back dat way, I think. But dat spell wrong.” Ten minutes later, it was the boy who proved wrong.

“But this is a crazy, strange happening!” Trevour announced. “I don’t understand it. This place exists only on dis piece of paper. Better to head back home and figure it, then come back another time.”

As he reversed out of what we’d all agreed was our last ditch, we noticed them. They slithered towards us with purpose and bad intentions. The shorter of them sported an olive-green velvet jacket and dark shades. He whistled a sweet tune as he approached.

“Girlyourloveislikewildfiyaaaaah….”

The other two came up quickly from behind him. The wiry one had a raised hook of a scar under his dead-fish eye; the other had pulled his knit cap over the top half of his face.

The velvet jacket man sidled toward Trevour’s door, but seconds later he seemed to stare directly at me instead. Something about his gait seemed strangely familiar.

His lips stretched in a crafty smile, “How de Empress?”

I gave a hostile nod.

He placed his hand on the driver side of the car’s roof and leaned in. “Boss man,” he nodded to Trevour. “Whatta gwaan?” He surveyed the back seat. “Mi sistren.” As he spoke, his compatriots moved towards the rear of the car. Dom watched the other two from the corner of her eye, and her stillness made us alert. Salome eased her camera under the front seat.

“Something’s coming; get ready for it!” Dom managed before it all spun out like in a nightmare that was so preposterous only your scream could jolt you awake. At first my mind rejected that it was happening at all—the flash of the knife at Trevour’s throat, that one of the men had Salome by the hair and seemed intent on dragging her through the window. Senseless thoughts collided. I’d never get to dance in those bejeweled, four-inch heel shoes I’d been saving—I’d never get to see what the sculptures might have become—I hadn’t jumped off the cliff in Negril yet—Why hadn’t I gone to Tunis that time?—Who knew exactly where we were? And then—Capo knew.

The man at the front pressed in close to Trevour, as intimate as a lover. “Pussyhole, come outta di cyar an’ gi wi di tings dem. Know how long we spot oonu an’ a wait.”

Bedlam erupted suddenly. Trevour alone stayed rock still. The third man reached for the handle of the van’s sliding side door, his eyes roaming wildly over the groceries in the back. The sound of the jiggling lock exploded in the shaken silence and catapulted Dom into action.

“De tiefin’ bwoy a try rob we!” The man reached his other arm into the open window and grabbed Salome’s wrist. In a flurry of limbs, she raked her fingernails hard across his face.

“Eyii gyal! Yuh gon’ pay fi dat!”

But she was a madwoman, scratching and tearing at will. Galvanized by her resistance, I pressed my head toward the front seat and bit down on the hand that held Salome’s hair, doing away with the useless, rising hysteria. Her screams shifted a few nearby curtains, but no one came to our aid. The third man managed to wrest the side door open and lunged for a twenty-pound bag of rice. We fought him like enraged Oya goddesses, grabbing at the bag until it ripped and a confetti of rice rained over us all. As Trevour wrestled with the hand at his throat, velvet jacket man’s lackey passed something to him. From the corner of my eye, I caught the flash of silver as the wiry one reached into the back of his pants. Dom saw it too. She clambered into the front seat and managed to throw the car in gear.

“Jesus Christ! Hurry!” The words burst from me like a mantra.

As we sped away, I glanced at my watch. It had all happened in a teaspoon of time. Only six minutes had passed. Our lives lost and recaptured in six minutes, in just three hundred and sixty seconds.

We all spoke at once. Our outraged chatter filled the car, followed by bouts of levity that lightened the mood.

“You should a seen Indigo fight off the boy with rice!”

Salome was shaken and there was a welt on her chin. She had been in worse scrapes than this on assignment. But still. We hugged tightly, knowing it could have gone much further south. Dominique said what I’d been thinking,

“Dat fucker! Who else know we was coming wid things? Send we on wild goose chase. Capo and dat wretch Adassa set we up! A trip into a ditch fi tek food out of him own daughter mouth!”

The thought sickened me. But I felt it was true. Capo, with that Adassa as the serpent in his ear. And I was almost certain the velvet-jacketed ring leader and the man always at Capo’s gate were one and the same. With all the excuses and reasons that would follow, the knowledge sat in my gut like a rock.

Of course, when later confronted, Capo denied it, fought tooth and nail against the very notion of it. Aunt Mercie cautioned, “Mine how you accuse.”

Adassa claimed it was all a mix-up and had an answer for every question I threw at her. Aunt Mercie was uncertain but erring on the side of caution.

“From de devil was a boy Capo cannot be trusted, but I don’t know dat him could go dat far. Desperation and opportunity make all kindsa dastardly things seem reasonable. But dat? Hard to say.”

But my swampy gut told me everything I needed to know. It roiled and bucked with a knowledge that was grievous to my soul. Would nothing I did move him? If all I’d made of myself could be reduced to this in his eyes—supplier of oil, rice, flour, soap, peas—what then was it all for? Why pretend there was anything of value left to protect at all?

Jamaican-born, US-based, Denise Campbell is an international communication consultant, content strategist, and travel and culture writer providing strategic communication planning and content development for such industries as international relations and development, media, healthcare, and technology. Formerly, she was head writer and communication lead at the Geneva-based Convention Against Torture Initiative, a UN-supported organization charged with global ratification and implementation of the UN Convention Against Torture. Denise’s fiction has been featured in the Caribbean Writer Vol. 27 and awarded the anthology’s David Hough Literary Prize for her short story “Where Dreams Die,” an excerpt from her debut novel Journey to Land of Look Behind. Denise has a bachelor’s in political science and English from New York University and a master’s from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Service and from American University’s School of International Service. She is fluent in Spanish and conversant in French.