STORY BY ELEANOR MARTINDALE

At the end of Part 2, we learned of Martindales who survived against the odds in Barbados.

A 1679 census shows a John Marting (an abbreviation for Martingdale, a common misspelling of our name) owning 10 acres, one slave, and no servants in the St. James Parish of Barbados. This John was the grandson of John Sr., from Part 1 of this tale, and 10 acres is the same amount of land his grandfather owned in 1638. In 40 years, the Martindales had not expanded their farm, nor sold up. It seems they had simply stayed put for three generations.

They cannot have been growing sugar, which demands labor, mills, and boiling houses—far more than one landowner and one slave could have managed alone. Other crops—ginger, indigo, tobacco—were still being produced on Barbados, and those farmers who could not afford to make the switch to sugar were also still growing food for themselves. This, it seems, must have been the Martindales’ lot. On this small farm had survived three generations of English immigrants, while around them, their compatriots left, or died of fever or alcoholism, or both. How had they managed?

A single fact from John Jr.’s life may give us a clue. In 1674, shortly before his death, John Jr. was fined 500 pounds of sugar “for two defaults in not appearing in the Troop.” The Troop—the Barbados Militia, established in 1640—functioned as the island’s police force. As shackled slaves began arriving by the thousands, the militia’s main role was to prevent slave uprisings. It was effectively a private army, subsidized by landowners with a vested interest in keeping slaves in their “proper” place. Why did John Jr. refuse to participate?

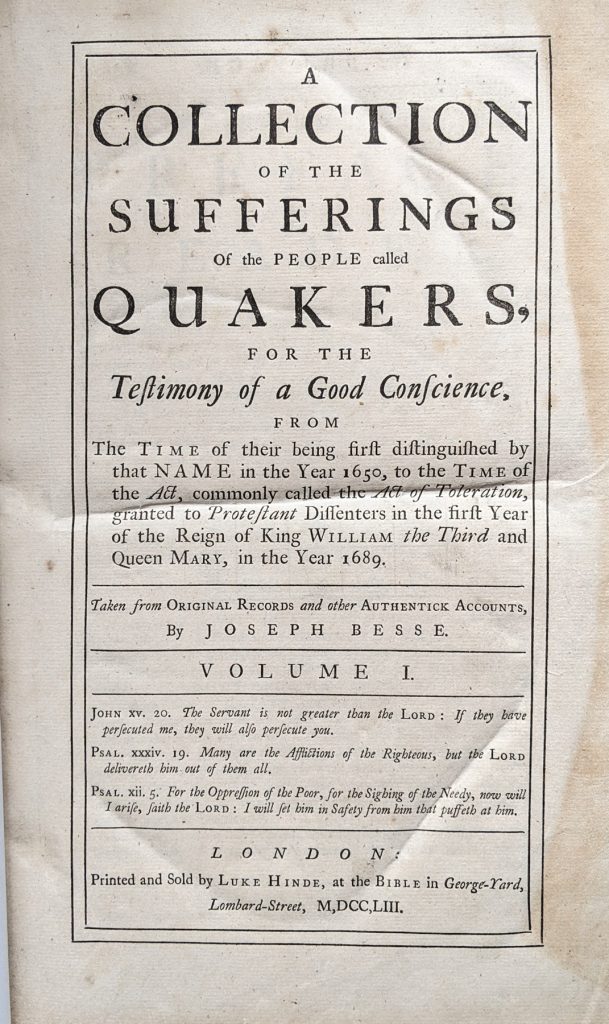

On its own, this detail does not seem much to go on, but it was recorded in a book entitled A Collection of the Sufferings of the People Called Quakers. Our John, it seems, was a Quaker. A pacifist, then. A man who refused to carry arms because of his religious beliefs. A puritan amongst pirates and drunkards. Was this the key to his survival? Why on earth was a Quaker living in Barbados just as the slave trade was beginning to boom? Quakers were the first abolitionists—what were they doing in a place where slavery was the kingpin of the economy?

Quakerism began in England around 1650, so my first intuition—that John Sr. might have left England due to religious persecution—did not hold up. His son must have converted to Quakerism in Barbados. And he was not alone.

In 1655, two missionaries, Ann Austin and Mary Fisher, landed on Barbados and converted several of the English immigrants. By the 1680s there were at least six Quaker meeting houses and five burial grounds on the island. The white settler population now numbered 20,000, and well over 1000 of those people were Quakers. In the 1670s Barbados was known as “The Nursery of Truth,” so full it was with Quakers.

As far back as 1688, The Germantown Protest, published by German and Dutch Quakers of Philadelphia, denounces slavery as unchristian. But the Barbadian economy could not exist without slavery, so what place did Quakerism have there? How was it that this island—a hotbed of corruption and drunkenness, where the torture of chattel slaves was an everyday occurrence—was also a hotbed of puritanism?

Courtesy of Wiki Commons.

The Quakers on Barbados, of course, did own slaves. The Dutch and German Quakers protesting slavery in Pennsylvania did not speak for all Quakers—in fact, they were a minority voice. Too many white settlers depended on slavery; the Quakers were not ready to challenge that.

But despite their acceptance of slavery as a cultural norm and economic necessity, the Quakers themselves were never fully accepted in Barbados by the majority Anglican community—these Quakers had the troubling habit of insisting that slaves were human beings and should be treated as such. They allowed—encouraged, even—black slaves to pray with their white masters in Quaker meeting houses. They wished their slaves to understand English—and the Bible—and to work in the fields as good Christians. In short, Quakers considered their slaves children of God, and, as such, deserving of respect. This is what the authorities wanted to suppress. Thus, as Quakerism grew, so did laws intent on quieting this disquieting religion.

A Quakeress and a Tobacco Planter in Barbados. Image courtesy of Wiki Commons.

In the English colonies, slaves were not allowed to convert to Christianity. It was feared that in learning to speak and read English and in inhabiting safe spaces, such as churches or meeting halls, the slaves would plot together and rebel. In 1675, after a significant slave revolt was suppressed in Barbados, the authorities passed a law that forbade Quakers to meet and pray with their slaves. Quakers were becoming outcasts in their promised land.

By the 1720s, most of the Barbados Quakers had either converted to Anglicanism or left for the North American colonies, where their beliefs would sit more easily. So it was with John Jr.’s family. From the 18th century onward, Martindales appear in the Anglican parish registers of the island.

While Quakerism did not survive on Barbados, it may well have helped John Jr. to survive. As a Quaker, he would have avoided those temptations that led to the downfall of so many: rum, promiscuity, and the promise of easy riches. His four sons all survived to adulthood and raised families of their own—a rare feat in this New World where most lived fast and died young.

So what of his children? Two of them, John III and James, appear to have stayed in Barbados, and the remaining sons, Isaac and William, emigrated to Rhode Island. Isaac became a notable sugar merchant in Newport, and his family were distinguished citizens of that town. It seems sugar and slaves eventually prevailed in this family, as Isaac was almost certainly trading his brothers’ sugar from Barbados.

By the time slavery was abolished in 1834, Martindales could be found in Barbados, Trinidad, Jamaica, and even the Indian Ocean’s Mauritius.

Remnants of a sugar plantation in St. John’s Parish, Barbados. Photo by Jim L. Webster

But what of that first John? We still know next to nothing about him. Why did he choose to sail into the

unknown all those years ago, when most people never strayed more than a few miles from their hometowns?

We know he was not rich, for he had only 10 acres of land, but in those 10 acres, we might just find a clue. Ten acres was the amount awarded to indentured laborers in Barbados once they had completed their term of contract. And given that it is in 1638 that John Sr. is listed as owning 10 acres of land, it seems entirely reasonable that he arrived in Barbados as an indentured laborer and worked essentially as a slave for seven or so years, the promised land his only payment.

Was John living in such poverty in England that his only way out was to sell himself to hard labor in the New World? Was he a young man with no family and no future, press-ganged into service? Or was he simply a criminal, sent to serve his sentence in the hot and hellish lands of the Caribbean colonies? We can conjecture as much as we like, but I don’t suppose we’ll ever really know.

Perhaps we can imagine John’s surprise, though, were he to learn that his humble name traveled through every level of New World society. It has been present in Barbados from the early, dangerous days of the first colony, through the vast expansion of the sugar and slave industries, to the abolition of slavery, the independence of Barbados in 1966, and now in its newest phase as a republic. The Martindale name—my name—is as intimately tied to the Caribbean as it is to Cumbria.

I never did find out whether I was related to the Barbados Martindales. While I don’t think John Martindale was a direct ancestor of mine, going so far back, it’s impossible to know for sure. And in the end, I don’t think it matters. All Martindales are related, if not by blood, then by place—and that place is as much a lush, green island where the Atlantic Ocean meets the Caribbean Sea, as it is a lush, green valley in northwest England.

Names run deep, and I am humbled by the sheer amount of history hidden in the three syllables of mine.

View of the Martindale Valley in Cumbria, England, with the writer. Photo by Bernard Salles.

Eleanor Martindale is a self-employed online tutor, teaching English literature, creative writing, and French to young people all over the globe. Born and raised in the U.K., she has spent all her adult life in France and now lives in French Catalonia with her French-Catalan partner, Bernard Salles, a professional musician. She plays the violin in several musical groups that Bernard runs, and when she isn’t teaching, she is usually found working on one of their orchestral projects. In whatever spare time she can find, she enjoys photography, drawing and painting, and of course writing.