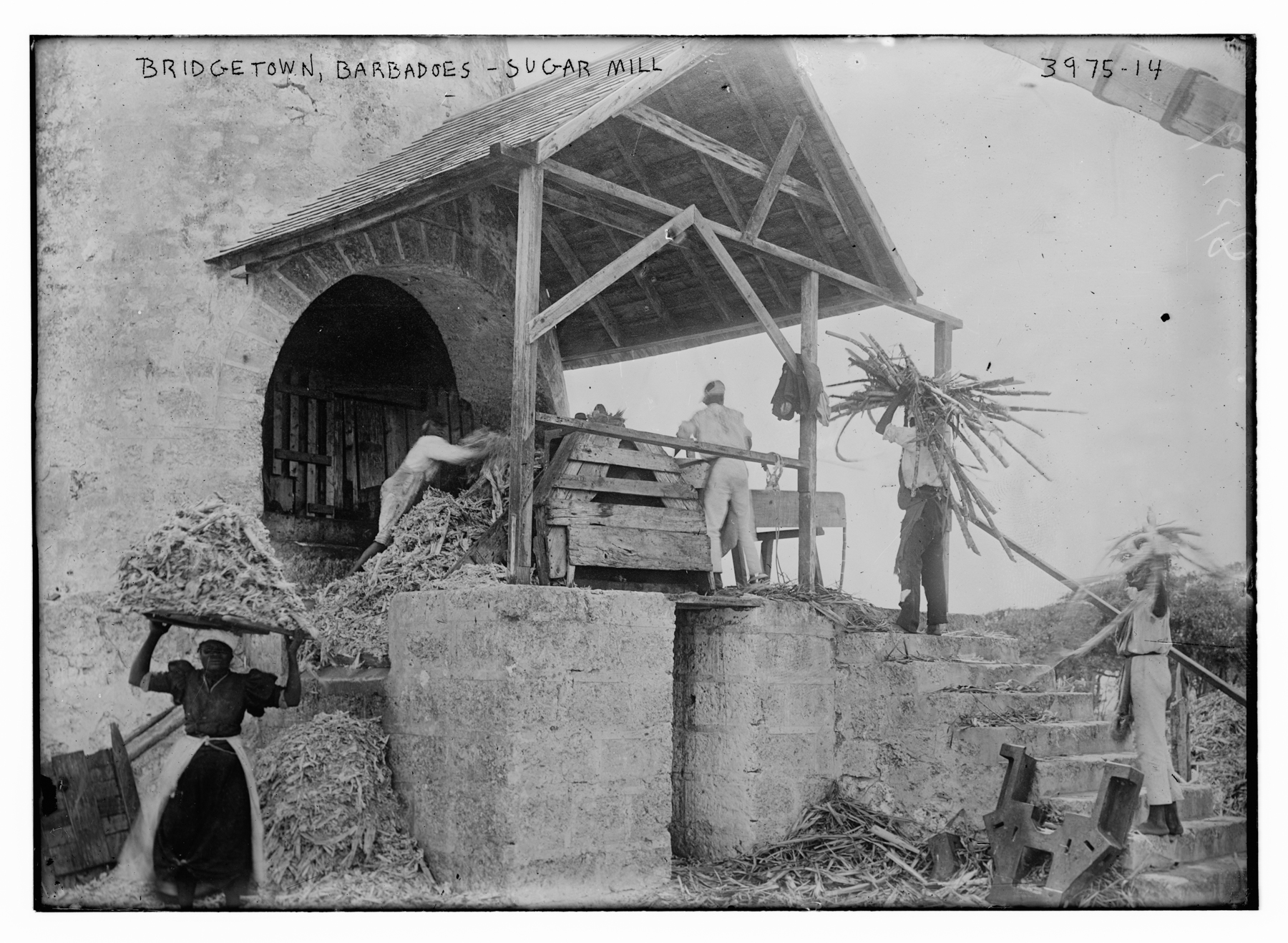

Sugar Mill in Bridgetown, Barbados, circa 1915-1920. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

STORY BY ELEANOR MARTINDALE

Picking up where we left off in Part 1 of this tale, upon discovering these early Barbados Martindales, I began picturing the lives of 17th century European settlers in the Caribbean, and the literature scholar in me couldn’t help but turn to Shakespeare. The Tempest was written during John Martindale Sr.’s lifetime and epitomizes a popular vision of a faraway, exotic island, uninhabited apart from strange spirits and magical creatures. Shakespeare, who probably never traveled outside of England and certainly never went to the Caribbean, used the collective imagination of his time to set the scene of a wondrous lush, green land with wild, fearful wind and waves.

When John Powell claimed Barbados for James I in 1625, it was uninhabited—the native Carib population had been wiped out by Spanish expeditions 100 years before. All that remained for the English sailors was land—ripe for the picking, as far as they were concerned—and a large population of wild pigs. It was much as Shakespeare described, although as the English settlers were to find out, there were no magical spirits to aid them.

Historic Barbados Map from 1670-71. Courtesy of New York Public Library and Wiki Commons

Life was hard, back-breakingly so. Everybody—from the poorest laborer to the richest landowner—lived without luxury. These English settlers had never felt such heat or humidity; the land they cleared was a tangle of unknown plants, full of trees whose trunks were as hard as rock. Fresh water was scarce; crops did not behave as they expected. Matthew Parker, author of The Sugar Barons, a history of the Barbados sugar industry, describes how the first settlers lived in caves until they managed to clear enough land to build simple dwellings. It was not until 40 Arawak natives were brought to the island to teach the settlers how to work the land and grow unfamiliar crops that they began to have some success in farming.

Slavery existed in the Barbadian colony from day one. Two years after his brother John had claimed Barbados for James I, Captain Henry Powell sailed a ship of 80 settlers and 10 indentured laborers to populate the island. Most of those laborers were unpaid workers from the British Isles, promised 10 acres of land at the end of their contract. Although some indentured workers had chosen to emigrate, some were press-ganged into service and were effectively slaves. Some were criminals, sent to serve their sentences in hard labor.

During the Atlantic crossing, Powell’s ship, the William and John, ran into a Spanish vessel, and, after a scuffle, the English settlers claimed the contents of the vessel as their own—fair game in the lawless ocean. The contents of this particular ship included six African slaves destined for the Spanish colonies in South America. Thus, Barbados became the first of the Caribbean islands to use slaves from the West African coast, and the seeds of the infamous triangular trade were sown. Six slaves in 1627 became 387,000 by 1807. From small acorns grow great and bloody oaks.

This image depicts the dwellings and recreational activities of the enslaved people on a plantation in Barbados indicating how they maintained and developed aspects of their cultural heritage through elements like music, dance and food. However, the remorseless toil of the plantation, represented here by the fully-grown sugar cane in the field and the windmill and boiling house in the background, was never far away. Photo by Neele and Son; Ralph Stennett, circa 1818. Image Courtesy of Wiki Commons.

In the 1640s, a few rich settlers began producing sugar—a difficult, labor-intensive crop financially viable only through the heavy use of slaves. As Parker writes, sugar would become in the 18th century what steel was in the 19th and oil in the 20th. There was money to be made in sugar, and Barbados was the place to make it.

“Men are so intente upon planting sugar that they would rather buy foode at very deare rates than produce it by labour, soe infinite is the profitt of sugar.” So reads a letter written in Barbados in 1647, quoted by Parker in The Sugar Barons. Barbados was too small an island to produce both sugar for the increasingly sweet-toothed Europeans and food for its own inhabitants—and given the choice, most preferred getting rich over toiling in the fields to produce their own sustenance.

Despite the boom in the sugar industry, life on Barbados remained desperately hard. Drought, hurricanes, and disease killed many. The slaves brought not only cheap labor but dangerous new illnesses too. Whereas Europeans had brought smallpox and influenza to the Americas, African slaves brought yellow fever to the plantations. In 1647-48, about a fifth of the population of Barbados was killed by yellow fever, and according to Parker’s book, as a general rule of thumb, around a third of all Europeans died within three years of arriving in the Caribbean. Besides natural disasters and deathly disease was the ever-growing scourge of rum. Thomas Modyford, a Royalist escaping retribution in the West Indies after the English Civil War, commented that Spanish traders “at their first coming wondered much at the sickness of our people until they knew the strength of their drinks, but then wondered more that they were not all dead.”

On top of all this, the ratio of men to women was around 8 to 1, and few families survived more than a couple of generations. Two-thirds of marriages left no children at all. All the while, rich landowners began buying up smaller plots for the ever-growing sugar industry, while smallholders left for an easier life in the New England colonies.

The Martindales, it seems, survived against all the odds. But who were they?

See Part 1 of this miniseries here, and come back to Anthrow Circus next Monday for the final chapter in this Martindale family story!

Eleanor Martindale is a self-employed online tutor, teaching English literature, creative writing, and French to young people all over the globe. Born and raised in the U.K., she has spent all her adult life in France and now lives in French Catalonia with her French-Catalan partner, Bernard Salles, a professional musician. She plays the violin in several musical groups that Bernard runs, and when she isn’t teaching, she is usually found working on one of their orchestral projects. In whatever spare time she can find, she enjoys photography, drawing and painting, and of course writing.