BY JONATHON GEELS

PHOTOS BY JILL DEVRIES

Consider the shape of public spaces with us via a series of articles from our resident landscape architect.

Photo by Jill Devries

Photo by Jill Devries

Design processes, especially in the built environment, tend to progress on very similar trajectories: a client with an idea engages a designer to turn that abstract idea into a concrete product (sometimes literally concrete). Many problems with this approach come to mind, but the one I would like to focus on is the notion of genius and where good ideas come from.

If your notion of genius is embodied by the lone patent clerk in some back office slaving away on the theory of relativity, then you’re imagining a process that is very non-participatory. Similarly so if you expect the next great American novel to come from someone typing away in a wintery log cabin, while the public waits to be amazed by the author’s genius.

Looking at the standard model of design practice, we see similar perceptions and deferred participation, which often results in dismissing the idea of design as a luxury. If design lacks engagement and is not necessary, we relegate the spaces we live and work in, at best, to mediocrity, and in the worst case, these spaces become unhealthy, economically and environmentally unsustainable, and not functional. The implications of a dismissive design process on our public spaces is dire.

Along the same lines, built-environment projects—like plazas, streets, or parks—take a lot of social, political, and economic capital to come to fruition. They take a long time from start to finish, often evolving over years. With all of this gravity, it can be difficult to change the course of a project. So even if a project begins with an idea that is not fully explored or is outright bad, the ability to make changes is limited. With so much effort being put into projects of this nature, when criticisms are brought up, the natural inclination is to be defensive or dismissive, which serves no one’s best interest.

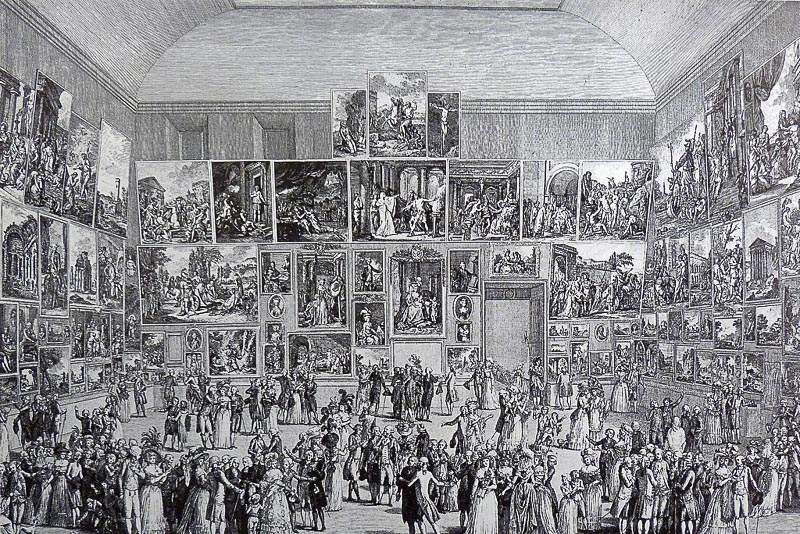

The Paris Salon and Genius of Collaboration

Around the time I launched the 100 Ideas Project, I had been reading about the Paris Salon in the mid-1800s. It was an exhibition of all the different artwork in Europe at that time. If you were able to get a piece of artwork into the Paris Salon then you were officially an artist and a financially stable career was secured, something artists still find hard to come by. Thousands and thousands of people would come to this exhibition, which gave artists a certain amount of notoriety, thus enabling them to secure future commissions. To have a piece displayed at the Salon, you had to adhere to Renaissance ideals, namely presenting scenes of history, mythology, or religious content that were technically perfect. This meant no visible brush strokes and often mathematically composed perspectives. Afterward, while financially stable, these artists were often relegated to relative anonymity because of the sheer volume of work collected at the Salon.

Also in the mid-1800s, a small group of artists met regularly at the Parisian Café Guerbois, each lamenting their inability to gain entry into this Salon. They submitted many paintings, but their ideals of what art was differed from the Salon’s ideals. The Salon saw art as needing to be this perfect representation that depicted real moments of history sans brushstrokes. But the Café Guerbois group liked to paint everyday life. They wanted viewers to see the brushstrokes; they wanted viewers to see the nitty-gritty of the work’s composition.

Banding together, though shunning any specific title, this group of artists developed their own exhibition, one where their work wouldn’t get lost in the crowd. Presenting their own ideas of what art was might not have attracted the same type of crowds that the Paris Salon attracted, but they were able to show their work and find the audience that was supportive of what they found to be true. These interactions, discussions, and evolved artistic styles eventually led to the group becoming known as the Impressionists. Among them Cézanne, Monet, Degas, and Manet led a shift in thinking and culture that changed the way we look at the world.

Starting the 100 Ideas Project was really born out of reading about the effort the Impressionists put into expressing different ideas. Initially, the website was a type of professional exercise, but with more conversations arising from the posts, the project became less and less about the individual ideas themselves.

Even though the ideas addressed municipal problems and opportunities, the project became more about the idea of creative culture and sharing and how we manage that and how we interact with one another and how we put those ideas out there—not as something I want to hold onto and keep secret and work on by myself but as ideas to be shared in order to be formed into the best ideas possible.

The way to make things better is really to get community feedback and share these concepts, very similar to the way the culture is in Silicon Valley. There, professionals don’t hold on to these new apps and new ways of using the Internet. They want to share their concepts with business competitors to get the best feedback, to better hone and evolve them.

The Paris Salon, image provided by Wikimedia Commons

The Paris Salon, image provided by Wikimedia Commons

London streetscape by Jill Devries

London streetscape by Jill Devries

Photo by Jill Devries

Photo by Jill Devries

An Iterative Process

As the 100 Ideas Project enters its next iteration, it takes on similar attributes to both Impressionists and Silicon Valley collaboration paradigms, challenging our concepts of what failure is or what this interaction means to move these ideas forward.

The first time through the project, nine primary lenses were used: purpose, materials, mobility, technology, economy, scale, environment, context, and people. These different lenses, some more intellectually accessible than others, broke the project down into manageable portions. It is difficult to come up with a hundred ideas about a making a municipality better. Thinking of ten ideas on how to improve mobility within the community is a much easier task.

Still, because the exercise is primarily meant to generate a dialogue about keystone projects throughout the community, it was necessary to seek to use less academic lenses in future editions of the project (scale is hardly an accessible concept). Thus, the current version of the 100 Ideas Project uses weekly lenses that include pop-ups, public spaces, sacred spaces, neighborhoods, energy, streets, and trees, among others. Also, partnerships with community organizations, like the Parks Department, were established throughout the process to more thoroughly seek feedback and continued involvement.

Already in planning, the next phase for the project seeks to explore more purposefully the concept of open source design. With the goal of further breaking down the barrier of perceived luxury and with the goal of democratizing design, we can better leverage the latent collaborative expertise in our communities. As Tim Brown of IDEO states, “When you only have a single, central point of control, as the designer or architect, you will inevitably get a linear top-down design solution. But if you put the tools of design into the hands of many more people, then you will get something that is emergent and bottom-up.”

The Idea Salon, West Side Wednesday, and the Best Week Ever

May 29 – June 4 the City of South Bend, Indiana, will celebrate its first “Best.Week.Ever” event. In the hundred days leading up to BWE, the 100 Ideas Project has contemplated how to make that event the least hungry week ever, the most bike friendly week ever, the most sustainable week ever, the most equitable week ever, and so on.

Fundamentally, design is an optimistic way to view the world. That is: you have to believe in the ability to make something better. In this case, these ideas are opportunities to build a wave of optimism. As part of that wave and in collaboration with the West Side Wednesday group, an Idea Salon will be featured as a micro-experience within BWE’s Best Wednesday Ever featured event on May 31.

Part exhibition of the most recent project, part community planning event, and part discussion, the Idea Salon is both culmination and launchpad, aimed at putting ideas into action. A common mantra throughout the process has been, “It’s ok to steal the ideas, just make them better.” In this case, the goal is to simply make the community better, one idea at a time.

Be sure to visit the 100 Ideas Project website to be inspired by ideas your own community might start discussing and stealing and making better.

Photo by Jill Devries

Photo by Jill Devries

Jonathon Geels is a landscape architect currently based in South Bend, Indiana, and founder of the 100 Ideas Project. He enjoys solving problems by connecting people to new ideas through design, innovation, and advocacy. He is passionate about improving public health, the built environment, social equality, as well as resource management and hopes to engage other professionals with the same enthusiasm. Find him also on Twitter and Instagram.