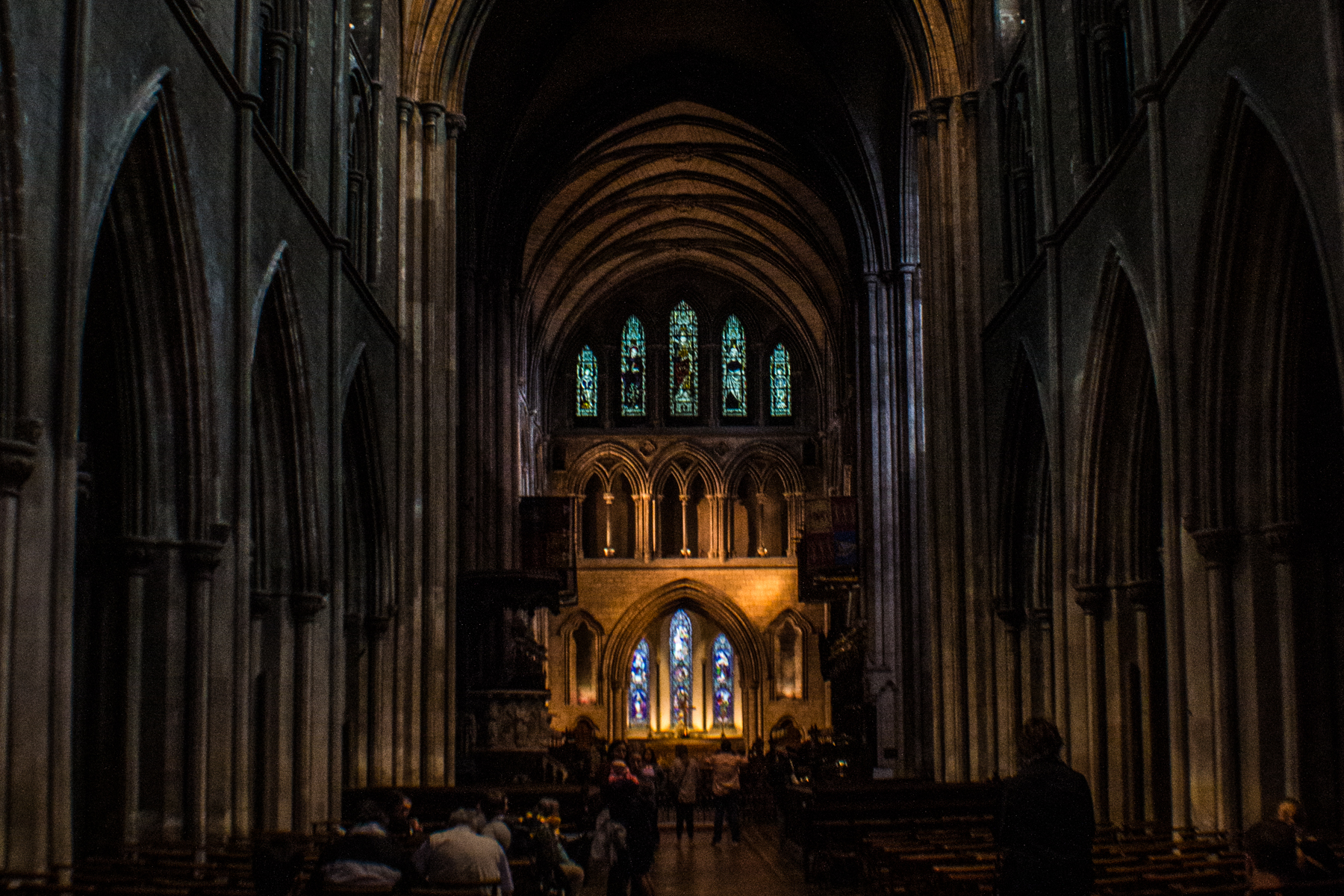

St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Ireland. Photo by JC Johnson.

WORDS & IMAGES BY CALLIE RADKE STEVENS

Behind the steeple of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin, clouds gathered and boiled, preparing for a storm or a show or something wild, surely. I zipped my coat all the way up as my husband and I picked our way down the narrow street.

I was determined to see at least a little bit of the city before we had to drive an hour south to where I was doing grad school research. This was Dublin, after all. We were there, and we had limited time. We had to see it. My husband, on the other hand, was tired and cranky and being exasperating. I was also tired and cranky, but I was going to have a good time. I was going to see the city. He was being annoying.

Down the street, Christ Church Cathedral loomed up on the corner, so big and boxed in by city that I had to stand across the street to fit it into the frame of my phone’s camera, timing the photo with the traffic. We hadn’t planned on attending church that Sunday, assuming the timing wouldn’t work. But the trickle of people nodding to the greeter at the doors extended the invitation to get out of the wind for a few minutes. Plus, I wanted to see the inside.

From the back, where we were sitting to be able to sneak out early, we could watch the choir’s entire processional to the front. Oh good, I thought as they punched out the first words of the first piece, it’s an angry one.

It occurred to me later that what I had thought of as anger is really a cry of anguish: Kyrie eleison, Lord, have mercy. The first part of a sung mass.

Clogher Head, Ireland.

The 15 months I spent living in London with my husband were thrilling, full of learning and new places. They could also be very lonely. Our work life and travel choices meant we were much less available than many of my classmates, and from April to July, we also hosted a revolving door of family and friends from home who enjoyed having a free place to stay in London. In other words, I often turned down invitations to pubs or picnics because we were out of town or trying to maintain the relationships we already had. It was good and hard simultaneously, lovely and lonely combined.

That doesn’t sound lonely, you might say. That sounds like you had people around all the time. But it was. Once, I fought back tears watching my classmates file out of the lecture hall. After class, when everyone else walked out with their new, fast friends, I sat on a bench in one of London’s many parks and ate leftovers, hiding my welling eyes behind sunglasses. How easy friendships seemed to everyone else, and how long it took me to feel natural around people.

I missed shared histories, shared memories, shared experiences. I missed people knowing all about me so that when I said, “I’m thinking about…” they could anticipate what I might say. I was exhausted of telling my story, of deciding which parts of it would communicate the me-ness I wanted to communicate. Even small talk is an anomaly in the city; when we went for a walk on Christmas Day, no strangers paused to wish each other a Happy Christmas!

The morning we arrived in Ireland, we had flown directly from Germany after spending a few days in the mountains with a visitor from home—and after hosting her in our one-bedroom flat for 11 days before that. It was an early flight, and there was a whole debacle with the bus from the airport when we didn’t have exact change (a mistake for which I blame the ubiquity of contactless payments in the rest of Europe). I would spend the entire week working with Irish farmers I’d never met for my grad school research and had that familiar stomach twistiness I get before extended interviews. We’d been awake since 3 or 4 a.m.

Clogher Head, Ireland.

In interviews, the film composer John Powell tells a story about choirs. A group of producers told him they weren’t sure about one of the pieces he’d written for a film. It wasn’t evocative enough and didn’t elicit quite the right emotional response. Powell went back to the studio and added a choir. This time, the producers loved it. Powell hadn’t changed any other part of the piece.

While Powell tells this as a comical anecdote and perhaps a lesson in how to manage producers, the story also illustrates the power of voices in music. The power of human voices lifted in collective song thrums at the deep part of us that knows we’re all spiritual beings muddling through an earthly life.

After the weight of the last several years, I’ve more often found myself with tears in my eyes while listening to live music. I get caught up in the swelling of human voices working as one. Whether in harmony or in dissonance, it doesn’t matter. They are still sounding out to communicate something, to tell a story together.

Giant’s Causeway, Ireland.

Churches are common in Europe, and that visit to Christ Church in Dublin was not the first or the last time my husband and I sat on the hard benches of cathedrals, abbeys, and chapels. I cannot remember most of sermons we heard in them, but I can tell you about the time a choir in Westminster Abbey sang Morten Lauridsen’s “O Magnum Mysterium.” It was a glimpse of the divine, a few minutes when the veil between worlds was lifted an inch. The hundreds of people in the audience seemed to sit completely still as the voices hung in the air, transcendent. When it ended, I felt as though I needed to gasp for air.

I can tell you about the moment during a Christmas service in St. Paul’s in London when the choir stopped to sing amidst the congregation, when the basses and baritones stood around our wing of the cathedral. Their voices, punctuated by the higher harmonies far across the cathedral, grounded me in something more whole. The cathedral itself became irrelevant in that moment; the very earth was singing.

With sacred choral music, I can participate in something that doesn’t ask anything of me. In the purest form, the voices say, Here is beauty; come and sit in it. Here are the laments, the praises, the seeking that you are feeling surrounding you. I found I did not even have to be the one singing to travel down the conduit to grace and intimacy.

Choral music is unique, in that we don’t commonly hear groups of people singing in unison. And those voices together don’t sing about ordinariness on a human level but rather of non-tangible, spiritual things. They sing of love, hate, God, creation, death, beauty, longing—and loneliness, too. Laments and praise together.

In the mass that morning in Dublin, as in all sung masses, the Kyrie was not the end. The end is Agnus Dei, preceded by Benedictus: the blessing. As we sat in the church, my breathing slowed and the constriction in my chest released. As as my husband and I left, we each took a deep breath. We were about to drive through Dublin’s traffic. We were about to enter a week of on-site graduate school research at various locations, meaning even more travel. But now, I could remember the Benedictus, and my eyes could see the blessing.

Gap of Dunloe, Ireland.