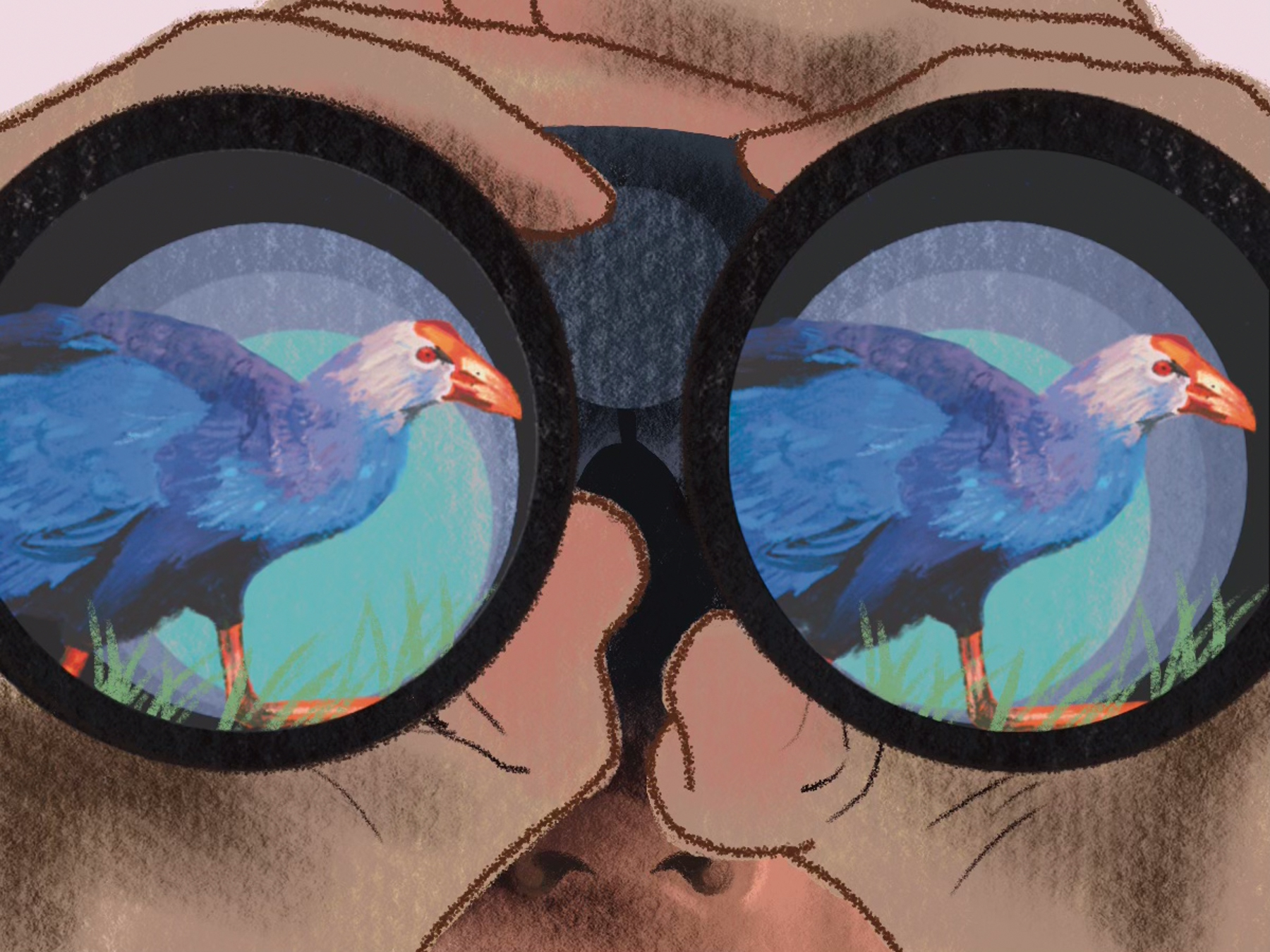

Illustration by Jillian Duke.

STORY & PHOTOS BY MAX WEAKLEY

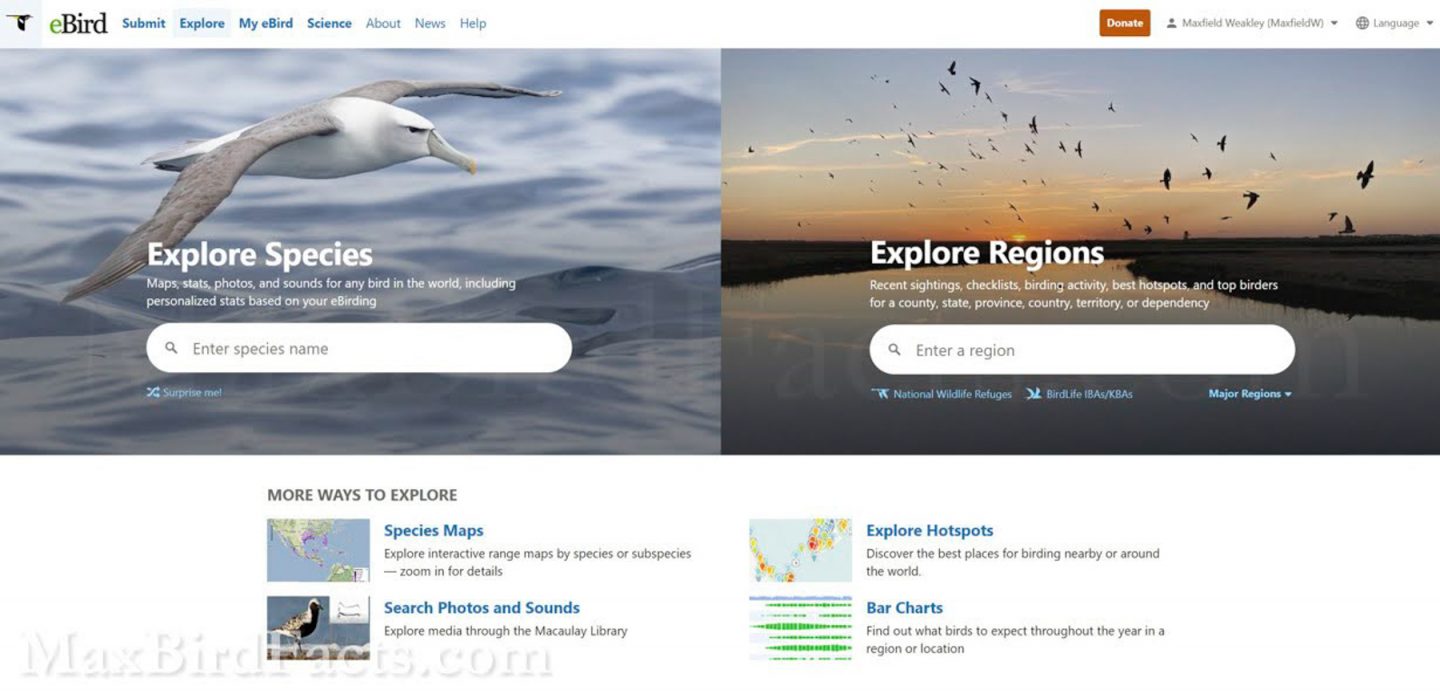

A few years ago, when I was just starting to get serious about birding, I devised a plan for the Monday after my 24th birthday. The weather in central Florida was forecasted to be partly cloudy, with a high of 80 Fahrenheit and a low of 70, so I knew I wanted to be outside. I pulled out my laptop and logged onto eBird.org.

Looking through the birding hotspots around my apartment, I zeroed in on one of my favorite places: the Orlando Wetlands, less than half an hour away. I had guided photo walks in the park before, so I had a good idea of what birds would be there during this time of the year.

Next, I looked farther east to Merritt Island, where I had been searching for Florida scrub-jays (Aphelocoma coerulescens) at least half a dozen times with no success. There was also Black Point Wildlife Drive on an island that my dad and I had visited around Christmas the past few years. A very rare bird was popping up on people’s lists at the Wildlife Drive, so I spent some time researching and studying those lists.

With these three locations in mind and the eBird app downloaded on my phone, I decided to do a Big Day.

But what is a “Big Day?” Essentially, a Big Day is when someone tries to find as many species of birds as possible in one 24-hour period. Cornell University’s Lab of Ornithology holds an annual Global Big Day on the second Saturday of May, but that doesn’t mean a person can’t try for a personal Big Day any time.

Some people prefer to achieve a Big Day all within a particular zone, such as within county lines, while others go for the highest total species regardless of location. I tend to travel wherever the birds are, regardless of borders. I reason that some birds are virtually impossible to spot in certain areas while they are a common sight in others. Why waste hours searching for a bird in one place where it is unlikely to be found when I can drive a short way to another county and locate it immediately?

So, that night, I went to sleep with the goal of finding as many birds as I could and finally encountering those evasive scrub-jays.

The Morning

Waking up at 7:00 a.m., I rolled out of bed and headed downstairs to make some coffee. After filling my cup, I walked out the back door to check the weather. It was splendid. The air was crisp and cool, with the sweet smell of magnolia blossoms wafting through the breeze. A quartet of boat-tailed grackles (Quiscalus major) sang on my neighbor’s roof, while my resident loggerhead shrike (Lanius ludovicianus) hopped along the branches of the tree in my little backyard.

My resident loggerhead shrike perched and waiting to wish me luck on my Big Day.

I checked my phone to see if the forecast had changed since the night before, and it hadn’t. So I headed back upstairs, grabbed my camera bag and keys, walked back downstairs, grabbed some trail mix from the pantry, and headed out the door.

Orlando Wetlands

Arriving at the Orlando Wetlands Park at 7:38 a.m., I was immediately greeted by a wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) just outside the gates, so I opened the eBird app and started a list.

Adult female wild turkey staring at me.

After parking, I grabbed my camera, pocketed a spare battery, and headed to the trailhead. Passing the construction zone for a coming visitor center, I saw a very sociable palm warbler (Setophaga palmarum) and several wading birds.

Walking down Night Heron Lane, I got my first infrequent bird of the day, a gray-headed swamphen (Porphyrio poliocephalus). This bird is native to parts of the Near East, India, and Southeast Asia but was introduced to Florida in 1996 via escaped birds from private aviaries. Unfortunately, the swamphen directly competes with the native purple gallinule (Porphyrio martinica) for food and territory. As if on cue, a purple gallinule walked out of the vegetation a few yards away from the swamphen, only to be chased off by the invasive species.

Adult gray-headed swamphen, left, and adult purple gallinule, right.

Continuing down the trail, I added more than two dozen species to my list, many I expected to see at this park.

While looking over one of the large pools for more unique pecies, I spotted a Caspian tern (Hydroprogne caspia) flying high over the water and diving in to catch a fish. This shorebird was a bit unusual, but I had seen one in this pool the previous fall, so I wasn’t too surprised. Still, I stood and watched the graceful flight of the tern for a while. After photographing it, I moved on to see what was further down the path.

Adult Caspian tern flying, American coots in the water.

When I came around the bend, I saw a person almost standing in the water and asked what he saw. He told me he had found a sora (Porzana carolina), an exceptionally elusive bird to see in the open.

Adult sora emerging from concealment to forage.

He pointed out the sora, just on the edge of the vegetation. It wasn’t visible from the trail but clear as day from this vantage. Keeping an eye out for alligators, I leaned closer to the water to get a clearer view and snapped a few photos. I couldn’t believe I was seeing this bird so clearly, and it seemingly didn’t react to my presence in the slightest.

After thanking the man for sharing this incredible bird with me, I walked on to watch an active osprey (Pandion haliaetus) nest.

Osprey nest, with the female incubating while the male stands guard.

Though these birds are common worldwide, I still loved watching the pair interacting; one would fly off to catch fish in the surrounding ponds while the other remained in the nest. Since the second bird remained pressed to the nest, this was likely the female, presumably sitting on a clutch of eggs. I made a note to return over the next few weeks to watch for hatchlings.

Having my fill of watching the osprey pair, I walked down the trail a few yards and froze. Perched on the top of a dead palm tree was a stunning adult peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus). This was my second view of a peregrine in the Wetlands and the fourth I had ever seen.

Adult peregrine falcon perched, resting before setting off for the hunt.

These raptors are avian hunting experts, soaring high above flocks of unsuspecting birds until divebombing one at over 200 miles per hour, sucker-punching it with enough force to break the other bird’s neck. The fact that this formidable predator was here shouldn’t have been a surprise due to the abundance of prey. Still, the sight of this magnificent species was jaw-dropping.

After the falcon took off, likely in search of brunch, I continued down the trail to a wooded patch I knew was good for songbirds. There I added a gray catbird (Dumetella carolinensis), some common grackles (Quiscalus quiscula), and several northern cardinals (Cardinalis cardinalis) to my list. But the real prize was my first painted bunting (Passerina ciris).

Adult male painted bunting eating seeds in thick brush.

The entire encounter with the bunting only lasted 54 seconds, but it was enough time for me to get some decent photos through the brush. These songbirds are extremely shy and rarely come out to have their picture taken, so getting some passable images on my first encounter was invigorating.

This was the first time I had seen a painted bunting, which made it the first life bird or “lifer” for this Big Day. Lifers are birds someone has never seen or listed before. This colorful songbird marked my 190th.

Leaving the thickets behind and returning to the open wetlands, I meandered back to where I had seen the gray-headed swamphen. After spending a few minutes searching the reeds and tall vegetation, I found a pair of beautiful purple gallinules feeding on unopened water lily buds.

While photographing the gallinules, I spotted a lanky brown bird streaked in white with yellow eyes and skin around its beak. I almost screamed when I realized it was an American bittern (Botaurus lentiginosus) trying to skulk through the brush and use its camouflage to disappear.

Adult American bittern poking its head through thick vegetation.

I had seen this odd relative to herons and egrets the year before, but only in a fleeting glimpse and a mugshot of a photo. Just like last time, this bird slunk deeper into the weeds to hide from me. I didn’t want to waste this opportunity, so I climbed on top of a concrete drainage pipe cover and balanced there, scanning the tops of the reeds for any sign of movement. After waiting motionless for five minutes, with my camera raised and ready, I spotted the bittern sliding between the brush. It was heading toward a slightly more open patch of reeds, so I focused my lens there. After a few seconds, the bird entered my viewfinder, and I seized the photo I had hoped for.

Adult American bittern stalking through the reeds.

Watching the American bittern stalk deeper into the greenery, I hopped down from my perch and started walking back to my truck. After four miles of walking, I’d added 38 species to my Big Day’s list and had multiple, unforgettable photography opportunities. I felt luck was on my side for finding the Florida scrub-jays this time.

Max Weakley lives in Florida, where he graduated from the University of Central Florida in 2019 with a degree in biology. In his senior year, he took an ornithology class that opened his eyes to the fascinating world of birds. He started an Audubon campus chapter at UCF, where he has returned to talk about wildlife photography and life after graduation. He also has led photography and birding-centered walks in his state. Visit his website, MaxBirdFacts, to explore more.