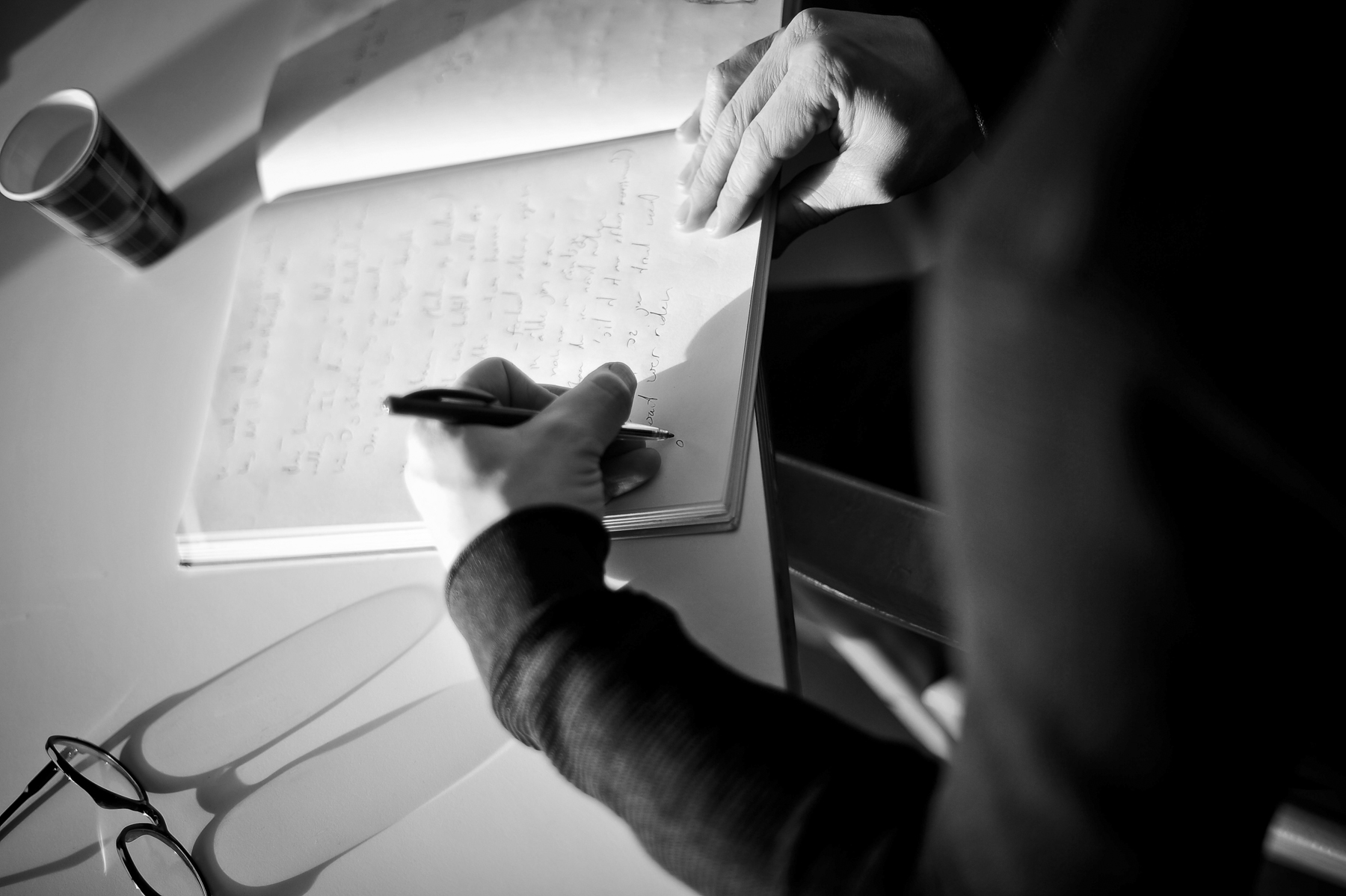

During Portraits in Poetry, Tsead Bruinja visited 11 residential care centers for the elderly in Friesland together with photographer Rosa van Ederen, musician Zea (Arnold de Boer), and four different colleague poets. Each artist spoke with a resident to create a new poem, photograph, or song with them. Besides these co-creations the artists also made a poem, song, or photograph for the residents on the basis of earlier conversations which often dealt with their rich life stories.

INTERVIEW AND ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY MIRTHE SMEETS

PHOTOS BY ROSA VAN EDEREN

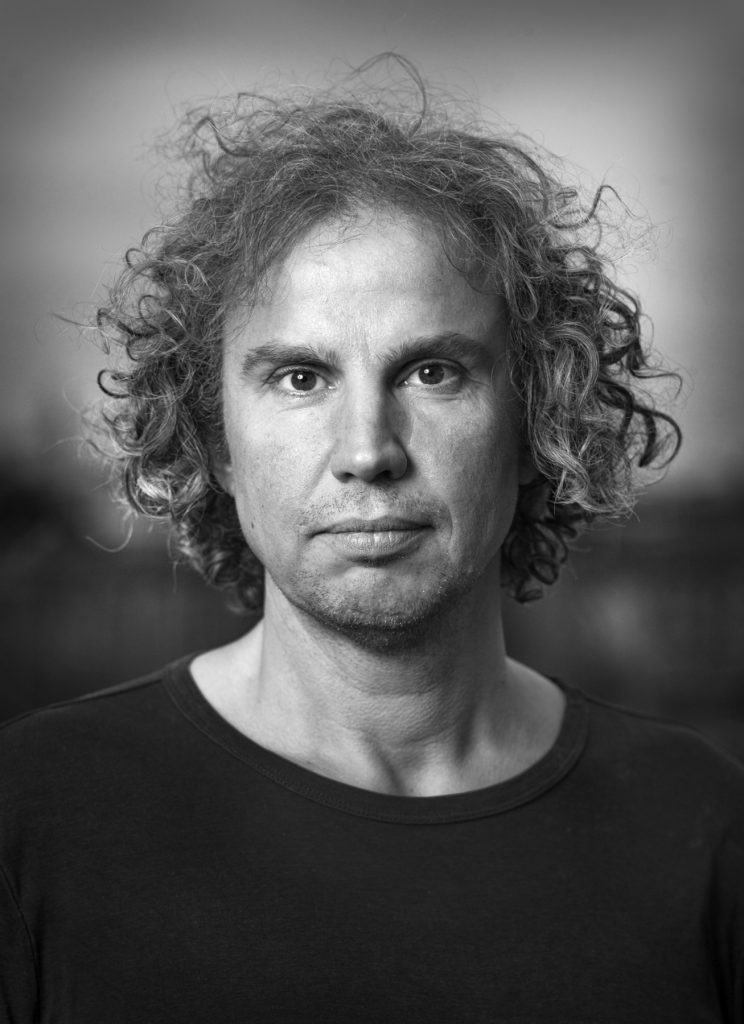

Tsead Bruinja was born in 1974, in Rinsumageest, Friesland, the northern part of the Netherlands where both Dutch and Frisian, the West Germanic language most closely related to English, are spoken. Bruinja is serving as the poet laureate of the Netherlands for a two-year term from 2019 to 2021. He also works as a creative writing teacher and has published several poetry collections, which have been nominated for Dutch prizes. In addition, he writes reviews, presents events and interviews, and performs in his own country as well as in foreign countries such as Scotland, England, Peru, Ukraine, and Zimbabwe. Some of his poems have been translated into English.

Mirthe Smeets, our poetry-loving Dutch journalist, spoke with Tsead Bruinja. Their conversation in Dutch was originally published by Meander Magazine (“Tsead Bruinja, de dichter die zich nooit vrij voelt, en telkens weer doorgaat”), and we are honored to publish an English version of the interview.

How do you see your development as a poet? How does the human figure in your poems change?

I started writing in English and I tried to copy the English rock singers I loved. I was playing with language. My first poetry collection was published in the Fries [Frisian] language, containing experimental and accessible work. I wrote in a kind of mutilated form of sonnet. I tried to make lines with 13 syllables instead of 10 syllables like in a normal sonnet.

Wow, but besides that…tough question! I’ve written 13 poetry books in total. What is my development? Some things have changed but other things stayed the same. There are subjects that I use over and over again. I have been a committed poet since forever, with a huge sense of justice, even before becoming poet laureate. I write about events that move me.

How do you deal with “wrong” interpretations of your work?

When an analysis is extensive and precise, I am okay with it. It doesn’t bother me. It is interesting to see the different interpretations. I just want to see that someone thought it over, uses arguments, does effort. … Once someone wrote a thesis about my poems. Loved it!

There are some reviewers who do not explain their opinion well. I try to let it go and try to look at it from a distance. I try to see—this could indeed be better, or no, it is fine like this.

Would you like to talk with reviewers who misunderstood your work?

No, [though] maybe in my head I think, “Read it again!” No, I’d rather have a beer with reviewers when I meet them. It is not done to ask them to defend their review. Too bad actually. It could be nice to discuss a text in an open way with them: Why did you look at the poem like that? What is your perspective? But I understand that the critics want to feel free while writing their review. They are busy people. I know how it feels, [since] I have written reviews myself too.

darling no one knows about the previous lives in which we passed each other by or missed the bus one of us was on or you were my sister my mother and it was doomed between us because too many years or a faith loomed up between us sometimes the distance must have been as solid as a continent with me for instance busy inventing fire while you and your lover were lighting candles on the other side of the ocean am I holding you too tight again I don’t want to crush you but I’m scared and glad at once that darling let time tear us apart as we die one by one we will fight back with bridges of words

Translation by David Colmer

Hear Tsead Bruinja read this poem in Frisian, the language in which he wrote the poem.

What do minor foreign languages mean to you?

My poetry is partly written in the Fries language, which distinguishes my work from other Dutch poets. People remember that, and they approach me as some kind of exotic poet. I easily get involved in projects about other minor languages. In Slovenia I participated in a translation project with poets from Corsica and northern Italy, and the only word that we had in common was bosk (forest). Wonderful. So yes, I am very interested in people who speak minor languages.

Was it hard to be a poet this year? Due to the pandemic your poet life must have changed?

Many projects were on hold. As a poet laureate I got different tasks, about COVID-19 for instance. Or I participated in projects from a distance: People could call me, or I could call them, and read poetry to them. I gave workshops, in the digital way.

Normally I would travel more. Performance is important to me.

Yesterday I was in Belgium, watching my girlfriend Heidi Koren during her performance as a poet. Another poet on stage said, “This is the first time on stage in five or six months.”

How odd is that! I mean, we could have never imagined a different life like this.

I do miss the satisfaction of performing. The contact with the audience. Contact with musicians who work with me sometimes. Hearing my poem out loud, changing it, putting some repeats in it—finishing the poem and creative process really.

But it will be possible again one day, I am sure.

You published your poet laureate poems and your own poems in the same poetry collection. Why?

I was just happy with both [sets of] poems. And before being poet laureate I sometimes wrote for clients too. When it was good enough, I just published it. Now it felt good too. The poems fit together to form the whole. I do not know yet what kind of poetry book I will create next. I do not tend to publish only poet laureate poems, in a chronological order. I rather make a composition, I focus on the content, and add the things that fit in it and leave the other poems out of it.

while our hair grows thinner and the monkeys in the trees laugh while we keep on having to go up on the roof to replace the blown-off tiles while the doctor sees us more often in his coughing sniffling waiting room while the monkeys laugh while people die one after the other and never take their deeds with them into the grave the monkeys stay young and laugh while the farts and belches accompany you everywhere and your gut and lungs wear out while the sheltered spot under the trees tempts you the monkeys laugh at the fading strength of your apple-peeling hands you look at her or you look at the ground and all the while the monkeys’ hunger grows while forgiveness shrivels and anger only sheds its skin the monkeys laugh and anger stays young

Translated by David Colmer

View this poem in its original Frisian as well as the Dutch translation written by the poet.

Mirthe Smeets works as an editor and journalist and lives in Maastricht in the south of the Netherlands. She lived in France for some time and loves to meet people from all around the world. Sharing beautiful stories and cultural projects is one of her passions and is why she enjoys contributing to Anthrow Circus. Have any nice ideas? You can contact her at mirthesmeets@gmail.com.