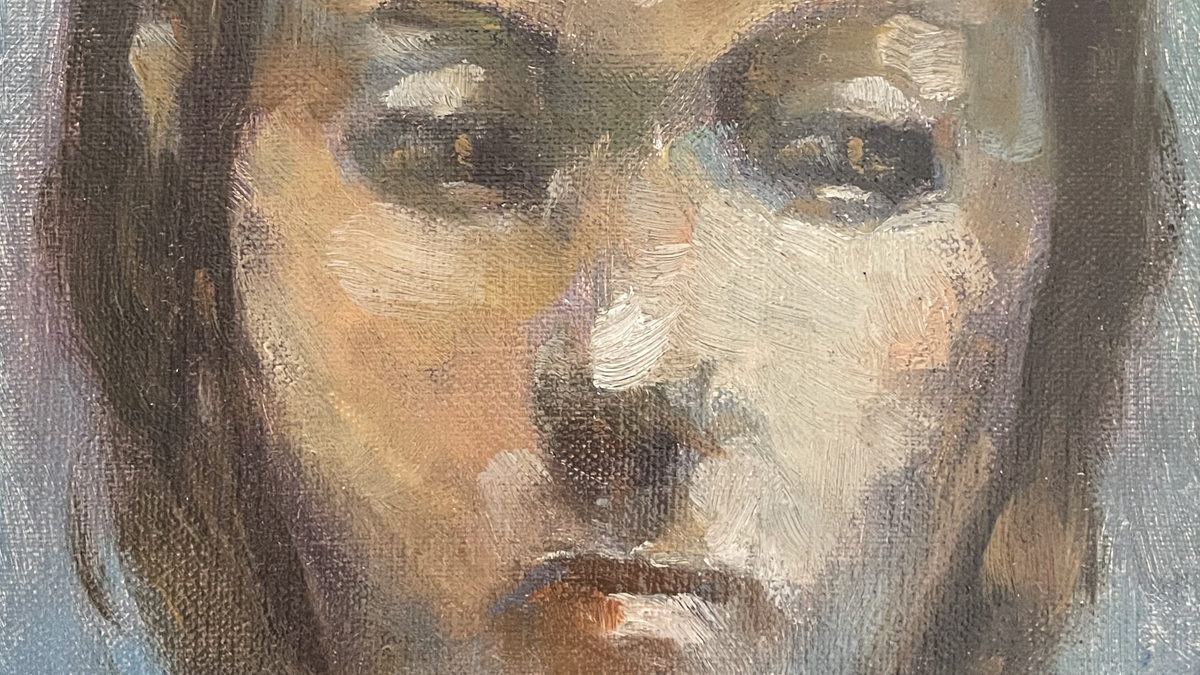

Painting of a woman by French artist Charles Pasino. From Kami Rice’s collection.

A BOOK EXCERPT BY SARAH DAWN PETRIN

An excerpt from “Me Too: A Global Crisis,” chapter 6 of Sarah Dawn Petrin’s book BRING RAIN: Helping Humanity in Crisis. Purchase the book here.

As an international relief worker whose career spans 20 years and 20 countries, I’ve worked to address many problems caused by war, disaster, and disease. But the one that has confounded me the most is sexual violence, which affects one in three women globally.

In order to end the cycle of violence against women, it’s important to understand why sexual violence is taking place.

Gender-based violence is rooted in gender bias and cultural norms that prefer men to women, denying women equal rights and opportunities. These biases are manifested in different forms of discrimination and harmful practices.

Sexual violence is not about sexual acts. It is fundamentally about power. It is about one person or group of persons overpowering another. This struggle for dominance can take many forms of abuse, including domestic violence, child abuse, rape, intimate partner violence, forced marriage, and psychological harm. These forms of harm based on one’s gender are also known as Gender-Based Violence (GBV).

Violence against women is everywhere, not only in developing countries but also in industrialized ones. It is especially prevalent during a conflict or disaster, when women and girls are at heightened risk. I’m going to share the stories of two women—a widow in Afghanistan and a child from Myanmar—that show how sexual violence knows no boundaries.

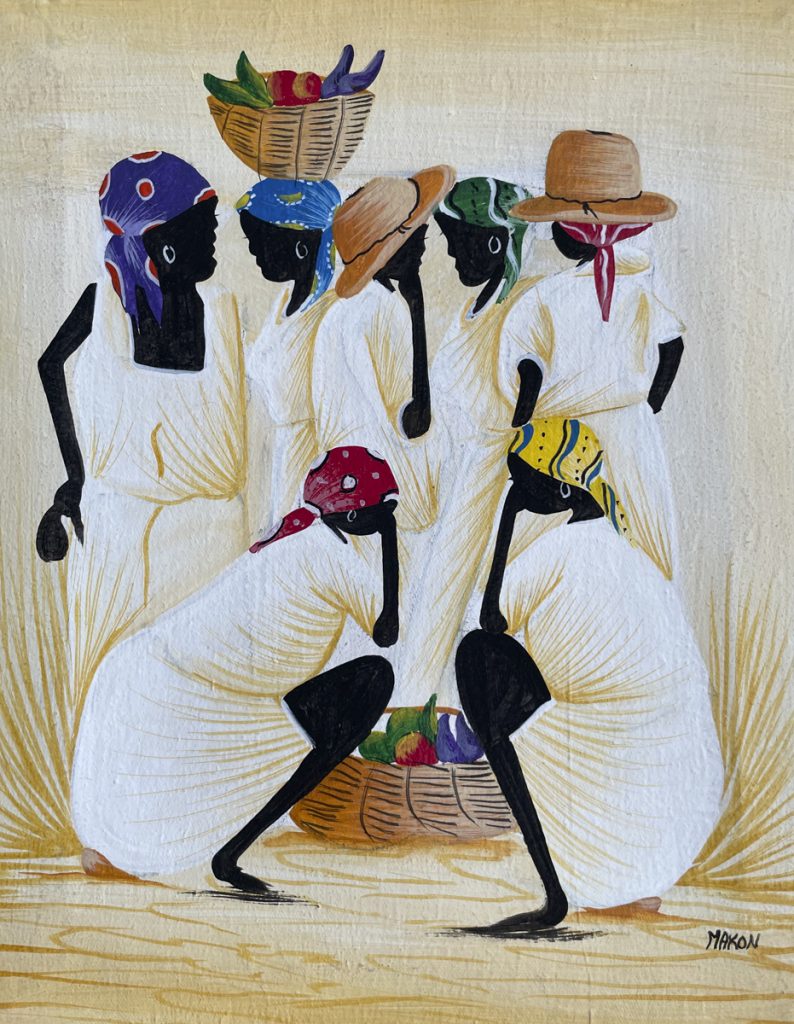

Women chatting during chores, painting by Haitian artist Makon. From Kami Rice’s collection.

Fatima, a Widow in Afghanistan

Fatima, a widow I met in Kandahar, a border town in southern Afghanistan, had lost her husband and both of her sons in the war. She wanted to travel to Kabul, the capital city, to be reunited with relatives, but police at checkpoints kept taking her out of the buses going north.

The problem for Fatima was that she did not have a travel pass. In Afghanistan, it is dishonorable for a woman to be alone in the company of men who are not family members. But as a widow, she no longer had a male relative to accompany her, and the young officers thought she was being improper by traveling alone.

As a protection officer for a United Nations program, it was my job to identify the needs of especially vulnerable people among the crowds of thousands of people in displacement camps. Finding out about people like Fatima, and finding a way to help them, was part of my job. Knowing that as a young woman I would also have problems going directly to the police, I decided that my best course of action was to take the situation up the chain of command and go directly to the governor of the province.

When I stood before the governor, there were many men around him waiting for important decisions to be made. I asked the governor to grant Fatima a special pass with his signature which would allow her to travel to the capital. As I made the appeal, the men surrounding the governor laughed.

“What good is this woman on her own? She is no use to anyone,” they smirked.

“That’s right,” I said. “What use is she to you? Let her go and be with her family.”

I handed the governor a letter I had drafted, offering his blessing for her travel. The letter also named her male relatives awaiting her arrival in Kabul. The governor signed it with his seal, and Fatima was on her way.

The men weren’t interested in having sex with Fatima, but they were interested in controlling her social mobility because of her gender. Travel was seen as a particular benefit in Afghan society, a benefit that was held by men, and other men jealously guarded this privilege.

Fatima needed an outside advocate to negotiate with those in power so she could freely exercise her rights. This is what humanitarian protection means. It means advocating for people at risk of violence and helping them on their road to recovery.

Sexual violence is not about sexual acts. It is fundamentally about power. It is about one person or group of persons overpowering another.

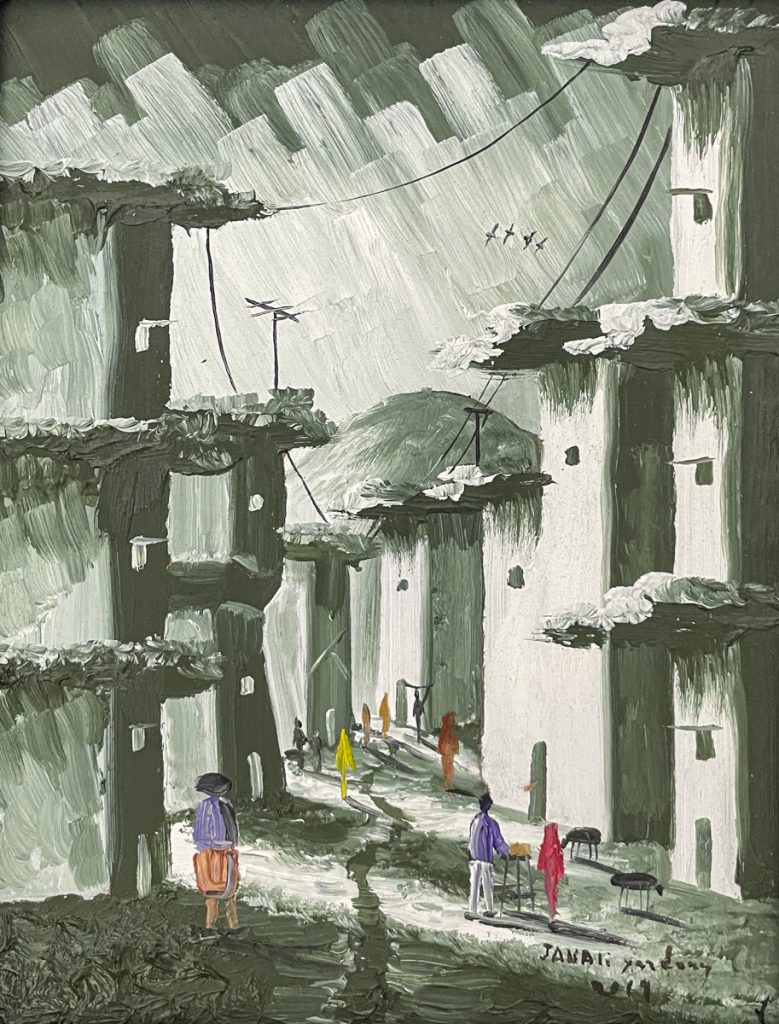

Old Kabul streets, painting by Afghan artist Janali. From Kami Rice’s collection.

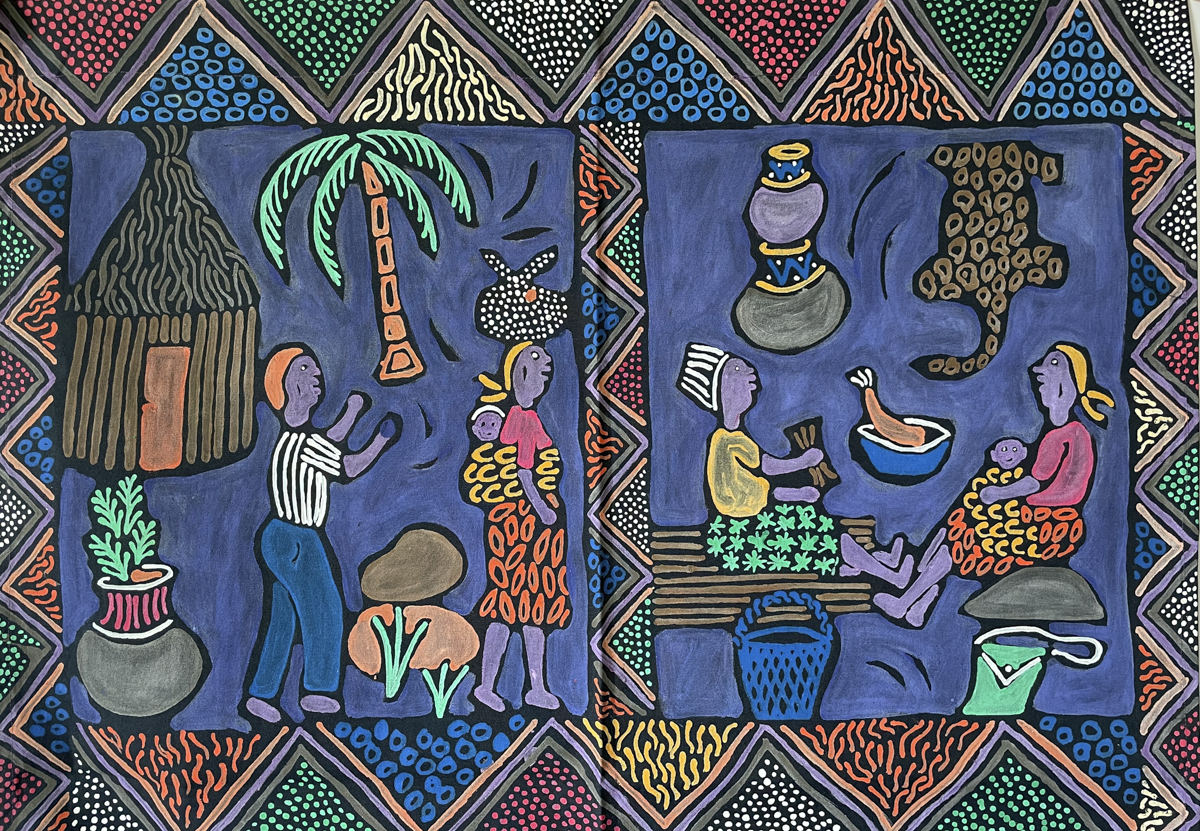

Domestic scenes portrayed in a tapestry painting on cloth, from Zimbabwe. From Kami Rice’s collection.

Mi, a Child from Myanmar

When I met her, little Mi was a five-year-old refugee from Myanmar, a country ruled by a military junta that has cracked down on democracy for years.

She was living in a large slum in Phuket, a coastal area in southern Thailand that had just been devasted by a powerful tsunami. For refugees from Myanmar, the impact of the overpowering ocean wave was about more than physical destruction.

Being foreigners made them ineligible for many forms of assistance and vulnerable to deportation back to a country where they were being persecuted.

Mi was an adorable little girl who wore pigtails and was missing her bottom front tooth. But she was not carefree, as most children are. Her parents worked long hours in the fishing industry, and unlike Thai children, migrant children were not allowed to go to school. That meant Mi was alone in the slum all day.

Yet, Mi found solace in a day care program funded by the organization I worked with. There were hundreds of children in the day care program, but the counsellors pointed out little Mi to me. They told me something strange was going on with her, and they could not figure out what it was. She kept disappearing from the other children.

I decided to shadow her during play time to figure out where she was going. Sure enough, one minute she was running around with her friends, and the next moment, she was gone. Since I was following her closely, I could see what she was doing.

She was hiding.

The labor camp where Mi lived was hidden behind five-star hotels and convenience stores. People were piled on top of one another, on top of a garbage pile. The conditions were abhorrent, some of the worst I had ever seen.

Mi lived in a place teeming with people coming and going to different jobs. People living there had two goals: making money and avoiding detection by the police in order to avoid deportation back to Myanmar. The care and protection of children was an afterthought.

Mi hid under a chair, crouching low with her little arms wrapped tightly around her legs and her head down. She was trying to make herself smaller so no one would see her. I knelt down on my hands and knees, peering under the chair to talk to her.

“Mi, why are you hiding? Don’t you want to play with your friends?”

“The men will get me. They are coming for me.”

“Not here,” I told her. “Here, you are in a safe place. Come out so you can play with your friends. See, they are waiting for you.”

I slowly coaxed her out from under the chair, and she returned to play. Afterward, my team discussed what more we could do. I increased the number of days children could play in the program, which meant hiring more staff and increasing the program budget. We also scheduled “home visits” for our social workers to check in on the children regularly.

When it was time for me to leave Thailand, I could not stop thinking about little Mi. Although I did what I could, it didn’t seem like it was enough. We suspected that the men taking her were police officers, and there was no accountability for the abuse of migrant children.

Without the care of her parents or school authorities during the day, Mi lacked protection. She could be taken and abused, and we suspected that she was. She lived in fear and did the only thing a child could do—run and hide.

As a female refugee child and a disaster victim, Mi was more vulnerable to violence. The best way to make her safe was to help her go to school. In addition to providing the day school, my organization also advocated with Thai authorities to allow all refugee children from Myanmar to go to school.

It is about addressing the underlying inequalities that make women and girls more susceptible to violence. It is about replacing risk with opportunity, both social and economic.

Painting by Charles Pasino. From Kami Rice’s collection.

The men will get me. They are coming for me.

A Safer World for Women and Girls

Keeping women and girls safe from violence is not about keeping sexual predators at bay. It is not about having men control themselves or making women less attractive in appearance. It is about addressing the underlying inequalities that make women and girls more susceptible to violence. It is about replacing risk with opportunity, both social and economic. In order to end sexual violence, we must create a world where even the very young and the very old—where a widow and a child—can live free from fear.

Women’s work at sunset, by Haitian artist Michelet Oléus. From Kami Rice’s collection.

Gender-based violence is rooted in gender bias and cultural norms that prefer men to women, denying women equal rights and opportunities.

Sarah Petrin is the author of Bring Rain: Helping Humanity in Crisis. She served as a humanitarian aid worker for over 20 years in 20 countries with United Nations agencies, the Red Cross, and nongovernmental organizations. She has advised governments and military organizations on the protection of civilians and prevention of conflict-related sexual violence in war zones.