Photos by Joanna Chattman

By Holly Wren Spaulding

Shortly after completing my last collection of poems, Pilgrim, published in 2014, I was introduced to a local artist whom I was hoping to hire to create a broadside from one of my poems. She suggested I take a private lesson from her instead, assuring me that it would shift my relationship to my poems in interesting ways. After all, poets and printers share a long and important history.

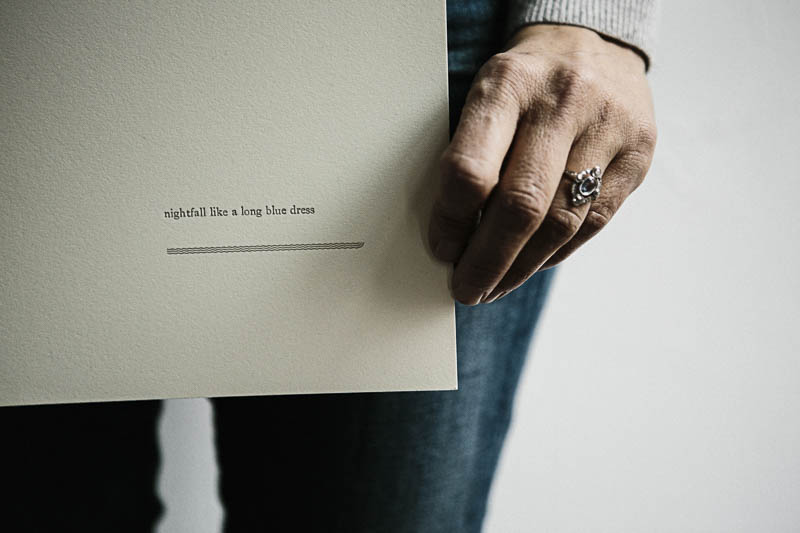

The process of setting type, one tiny lead letter at a time, and the intense focus this places on individual words and lines, requires attention, slowness, and a true commitment to each word. Due to the limits of time and my lack of printing experience, I decided I would print only brief excerpts rather than my poems’ full text. This idea has roots in my ongoing interest in short forms and concrete poetry and in my long appreciation of haiku.

Despite my inexperience, what I made is beautiful to me, in part because it accomplished something I’ve strived for in my poems for a while: radical simplicity, quiet, and room for the reader to think about a single image or idea at a time. I also enjoyed engaging with the visual elements of these spare essences of language, seeing them as art objects as much as I see them as poems.

I wasn’t exploring letterpress printing with any professional application in mind. It was winter, and I wanted to shake up my routine and do something for my own enjoyment. But the experience has impacted in significant ways all of the work I’ve done since then.

For example, I initiated an ongoing series of installations in New York City where we’re projecting similarly brief passages of text onto city structures as a way of inserting poetry into public spaces. More importantly, my current poetry manuscript, a book-length poem in fragments, wouldn’t exist without my exploring brevity and white space through letterpress printing.

What happens when we’re a beginner, again, and bring our creativity and sensibility to a process, without any of the expectations or self-judgment that saddles the work we do with an audience in mind? What happens when we make simply because we want to, or because it occurred to us, or because it’s our mode of being in the world?

These are questions I’ll explore here at Culture Keeper in an ongoing series of conversations with other artists of various disciplines. I’ll ask them to share the insights, new directions, and pivots that have come from side projects, experiments, and forays into what if.

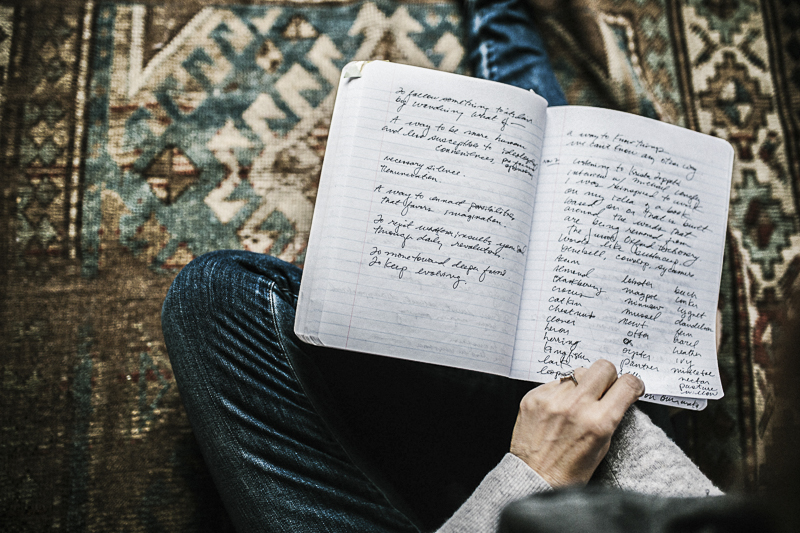

The fact is, most of this kind of exploration, and the paths we take to understand what it means, is invisible work. Most of the time, we don’t show it to anyone or even think of it in terms of “work” because it’s about something else to us. I want to talk with fellow artists about the things we make when no one’s watching, or when nothing in particular is at stake. And I want to talk about what happens next.

There’s a subversive element in this for me too. I’m a writer and teaching artist based in Williamsburg, Massachusetts, where I live with my husband, who is also a writer. We moved here a year ago, shortly after getting married, and we’re both at a stage in our lives where most days are dedicated to fairly focused, goal-driven thinking and writing toward specific ends, albeit creative ones. Yet I know that when I get to run off-leash for a while, things happen, including breakthroughs.

Thus, I want to create a space here to think about some of the ways artistic activity functions as a form of resistance within a culture that valorizes mindsets and methods that, by and large, fly in the face of deeply engaging with the unknown, or with anything else that can’t easily be defined, much less commodified. Instead of relevance, relatability, fame, or economic motivations, we’ll talk here about pleasure, beauty, autonomy, and figuring things out when we weren’t even trying to do so.

To make something is to act, to respond—to an idea, an impulse, an urge. To answer desire. So much creative work involves following combinations of inchoate, often inarticulate signals, and then translating them into some form, some thing in the world. We find out what it is or what it means only after we’ve been at it for a while. And very often, this happens only after facing a reckoning, and grappling with false starts or failure of some kind. This happens after undertaking fanciful or off-subject projects, then realizing that they’ve opened some pathway we needed in order to do whatever happens next.

Stay tuned for the first conversation, coming soon.

Holly Wren Spaulding is an interdisciplinary artist, teacher, and author, most recently, of Familiars: Poems (Alice Greene & Co., 2020). Holly is the founder and director of Poetry Forge, where she works with emerging writers to develop new work and complete books.